On Thursday, Pensions & Investments broke the story that CalPERS was putting its private equity benchmarks under review.

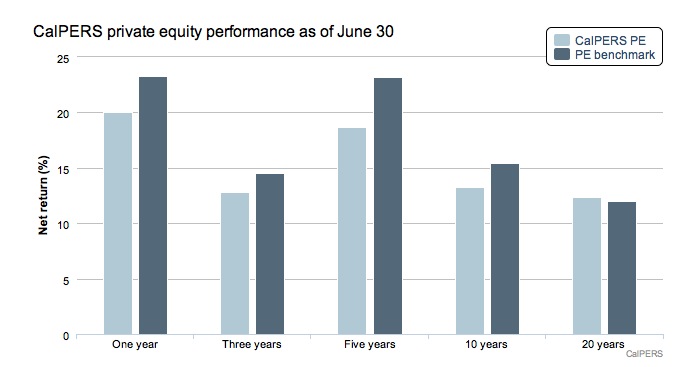

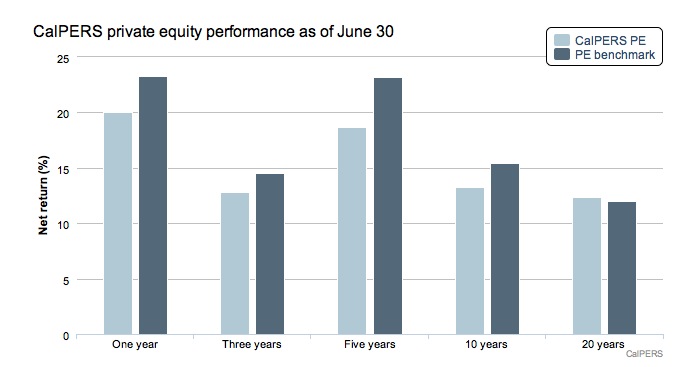

Beginning with the end of last fiscal year, the fund’s private equity portfolio has underperformed benchmarks over one year, three-year, five-year and ten-year periods [see the chart embedded in the post below].

CalPERS staff says the benchmarks are too aggressive – in their words, the current system “creates unintended active risk for the program”.

Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism has published a post that dives deeper into the pension fund’s decision – is the review justified? And is it enough?

__________________________________

By Yves Smith, originally published at Naked Capitalism

The giant California pension fund roiled the investment industry earlier this year with its decision to exit hedge funds entirely. That decision looked bold, until you look at CalPERS’s confession in 2006 that its hedge funds had underperformed for three years running. Its rationale for continuing to invest was that hedge funds delivered performance that was not strongly correlated with other investments. Why was that 2006 justification lame? Because even as of then, it was widely acknowledged in the investment community that hedge funds didn’t deliver alpha, or manager performance. Hedgies nevertheless sought to justify their existence through the value of that supposedly-not-strongly-correlated performance, or “synthetic beta”. The wee problem? You can deliver synthetic beta at a vastly lower cost than the prototypical 2% annual fee and 20% upside fee that hedge funds charge. Yet it took CalPERS eight more years to buck convention and ditch the strategy. Admittedly, CalPERS did keep its investments in hedge funds modest, at a mere 2% of its portfolio, so it was not an enthusiast.

By contrast, CalPERS is the largest public pension fund investor in private equity, and generally believed to be the biggest in the world. And in the face of flagging performance, CalPERS, like Harvard, appeared to be rethinking its commitment to private equity. In the first half of the year, it cut its allocation twice, from 14% to 10%.

But is it rethinking it enough? Astonishingly, Pensions & Investments reports that CalPERS is looking into lowering its private equity benchmarks to justify its continuing commitments to private equity. Remember, CalPERS is considered to be best of breed, more savvy than its peers, and able to negotiate better fees. But look at the results it has achieved:

And the rationale for the change, aside from the perhaps too obvious one of making charts like that look prettier when they are redone? From the P&I article:

But the report says the benchmark — which is made up of the market returns of two-thirds of the FTSE U.S. Total Market index, one-third of the FTSE All World ex-U.S. Total Market index, plus 300 basis points — “creates unintended active risk for the program, as well as for the total fund.”

In effect, CalPERS is arguing that to meet the return targets, private equity managers are having to reach for more risk. Yet is there an iota of evidence that that is actually happening? If it were true, you’d see greater dispersion of returns and higher levels of bankruptcies. Yet bankruptcies are down, in part, as Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt describe in their important book Private Equity at Work, due to the general partners’ success in handling more troubled deals with “amend and extend” strategies, as in restructurings, rather than bankruptcies. So with portfolio company failures down even in a flagging economy, the claim that conventional targets are pushing managers to take too many chances doesn’t seem to be borne out by the data.

Moreover, it looks like CalPERS may also be trying to cover for being too loyal to the wrong managers. Not only did its performance lag its equity portfolio performance for its fiscal year ended June 30, which meant the gap versus its benchmarks was even greater. A Cambridge Associates report also shows that CalPERS underperformed its benchmarks by a meaningful margin. CalPERS’ PE return for the year ended June 30 was 20%. By contrast, the Cambridge US private equity benchmark for the same period was 22.4%. But the Cambridge comparisons also show that private equity fell short of major stock market indexes last year, let alone the expected stock market returns plus a PE illiquidity premium.

The astonishing part of this attempt to move the goalposts is that the 300 basis point premium versus the stock market (as defined, there is debate over how to set the stock market benchmark) is not simply widely accepted by academics as a reasonable premium for the illiquidity of private equity. Indeed, some experts and academics call for even higher premiums. Harvard, another industry leader, thinks 400 basis points is more fitting; Ludovic Philappou of Oxford pegs the needed extra compensation at 330 basis points

So if there is no analytical justification for this change, where did CalPERS get this self-serving idea? It appears to be running Blackstone’s new talking points. As we wrote earlier this month in Private Equity Titan Blackstone Admits New Normal of Lousy Returns, Proposes Changes to Preserve Its Profits:

Private equity stalwarts try to argue that recent years of underwhelming returns are a feature, not a bug, that private equity should be expected to underperform when stocks are doing well. To put that politely, that’s novel.

The reality is uglier. The private equity industry did a tsunami of deals in 2006 and 2007. Although the press has since focused on the subprime funding craze, the Financial Times in particular at the time reported extensively on the pre-crisis merger frenzy, which was in large measure driven by private equity.

The Fed, through ZIRP and QE didn’t just bail out the banks, it also bailed out the private equity industry. Experts like Josh Kosman expected a crisis of private equity portfolio company defaults in 2012 through 2014 as heavily-levered private equity companies would have trouble refinancing. Desperation for yield took care of that problem. But even so, the crisis led to bankruptcies among private equity companies, as well as restructurings. And the ones that weren’t plagued with actual distress still suffered from the generally weak economic environment and showed less than sparkling performance.

Thus, even with all that central help, it’s hard to solve for doing lots of deals at a cyclical peak. The Fed and Treasury’s success in goosing the stock market was enough to prevent a train wreck but not enough to allow private equity firms to exit their investments well. The best deals for general partners and their investors are ones where they can turn a quick, large profit. Really good deals can typically be sold by years four or five, and private equity firm have also taken to controversial strategies like leveraged dividend recapitalizations to provide high returns to investors in even shorter periods.

Since the crisis, private equity companies have therefore exited investments more slowly than in better times. The extended timetables alone depress returns. On top of that, many of the sales have been to other private equity companies, an approach called a secondary buyout. From the perspective of large investors that have decent-sized private equity portfolios, all this asset-shuffling does is result in fees being paid to the private equity firms and their various helpers….

As the Financial Times reports today, the response of industry leader Blackstone is to restructure their arrangements so as to lower return targets and lock up investor funds longer. Pray tell, why should investors relish the prospect of giving private equity funds their monies even longer when Blackstone is simultaneously telling them returns will be lower? Here is the gist of Blackstone’s cheeky proposal:

Blackstone has become the second large buyout group to consider establishing a separate private equity fund with a longer life, fewer investments and lower returns than its existing funds, echoing an initiative of London-based CVC.

The planned funds from Blackstone and CVC also promise their prime investors lower fees, said people close to Blackstone.

Traditional private equity funds give investors 8 per cent before Blackstone itself makes money on any profitable deal – a so-called hurdle rate.

Some private equity executives believe that in a zero or low interest rate world, investors get too sweet a deal because the private equity groups do not receive profits on deals until the hurdle rate is cleared.

Make no mistake about it, this makes private equity all in vastly less attractive to investors. First, even if Blackstone and CVC really do lower management fees, which are the fees charged on an annual basis, the “prime investors” caveat suggests that this concession won’t be widespread. And even if management fees are lowered, recall how private equity firms handle rebates for all the other fees they charge to portfolio companies, such as monitoring fees and transaction fees. Investors get those fees rebated against the management fee, typically 80%. So if the management fees are lower, that just limits how much of those theoretically rebated fees actually are rebated. Any amounts that exceed the now-lower management fee are retained by the general partners.

The complaint about an 8% hurdle rate being high is simply priceless. Remember that for US funds, the norm is for the 8% to be calculated on a deal by deal basis and paid out on a deal by deal basis. In theory, there’s a mechanism called a clawback that requires the general partners at the end of a fund’s life to settle up with the limited partners in case the upside fees they did on their good deals was more than offset by the dogs. As we wrote at some length, those clawbacks are never paid out in practice. But the private equity mafia nevertheless feels compelled to preserve their profits even when they are underdelivering on returns.

And the longer fund life is an astonishing demand. Recall that the investors assign a 300 to 400 basis point premium for illiquidity. That clearly need to be increased if the funds plan slower returns of capital. And recall that we’ve argued that even this 300 to 400 basis points premium is probably too low. What investors have really done is give private equity firms a very long-dated option as to when they get their money back. Long dated options are very expensive, and longer-dated ones, even more so.

The Financial Times points out the elephant in the room, the admission that private equity is admitting it does not expect to outperform much, if at all:

The trend toward funds with less lucrative deals also represents a further step in the convergence between traditional asset managers with their lower return and much lower fees and the biggest alternative investment companies such as Blackstone.

So if approaches and returns are converging, fees structures should too. Private equity firms should be lowering their fees across the board, not trying to claim they are when they are again working to extract as much of the shrinking total returns from their strategy for themselves.

Back to the present post. While the Financial Times article suggested that some investors weren’t buying this cheeky set of demands, CalPERS’ move to lower its benchmarks looks like it is capitulating in part and perhaps in toto. For an institution to accept lower returns for the same risk and not insist on a restructuing of the deal with managers in light of their inability to deliver their long-promised level of performance is appalling. But private equity industry limited partners have been remarkably passive even as the SEC has told them about widespread embezzlement and widespread compliance failure. Apparently limited partners, even the supposedly powerful CalPERS, find it easier to rationalize the one-sided deal that general partners have cut with them rather than do anything about it.

Photo by TaxRebate.org.uk