Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Elliot Blair Smith of MarketWatch reports, How the Teamsters pension disappeared more quickly under Wall Street than the mob:

Real estate investments in Las Vegas casinos and hotels once threatened the integrity of a Teamsters pension fund that the federal government wrested away from corrupt trustees and organized crime after five years of legal battles.

A quarter-century later, the professionals who replaced them—Central States Pension Fund administrators; the Goldman Sachs & Co. and Northern Trust Global Advisors fiduciaries; and Department of Labor regulators—stood watch while the financial markets accomplished what the mob had failed to: which was to smash the fund’s long-term solvency with massive money-losing investments.

The debacle unfolding at the $16.1 billion Central States fund in Rosemont, Illinois, is a cautionary tale for all Americans dependent on their retirement savings. Unable to reverse a decades-long outflow of benefits payments over pension contributions, the professional money managers placed big bets on stocks and non-traditional investments between 2005 and 2008, with catastrophic consequences.

When the experiment blew up, rather than exhume the devastated portfolio to better understand the problem—and perhaps seek accountability—Central States administrators lobbied Congress to pass legislation giving them authority to cut retirement benefits by up to 50% after Treasury Department approval.

That’s close to Central States’ astonishing 42% drop in assets—and a loss of about $11.1 billion in seed capital—in just 15 months during 2008 and early 2009. And while the investment losses are not the source of the retirement plan’s unsustainability today, they accelerated the pension’s problems, and almost certainly made the benefits cuts deeper. The professionals made more money disappear in a shorter period of time than the mobsters ever dreamed of.

The Treasury Department under Special Master Kenneth Feinberg—who previously administered the 9/11 victims fund, and kept a rein on executive compensation at financial companies that received taxpayer assistance during the financial markets crisis—now has until May 7 to review an 8,000-page application by Central States to reduce the average pension benefit by 22% for more than 400,000 American workers, retirees, dependents and survivors.

In practice, some pensioners approaching retirement age—like 64-year-old Thomas Holmes of Avon, Indiana—expect to see about a 50% benefit cut after 31 years of hard work. And while Congress and the Central States administrators may have correctly identified and assessed one side of the problem—insufficient pension contributions to pay for benefits obligations—I’m suggesting that the fund’s investment portfolio also went off track, possibly beginning in 2005, or earlier.

That’s when federal tax authorities agreed to defer a statutory funding-deficiency notice for a decade, under an accord that required Central States to immediately begin repairing the pension’s finances. And it corresponds to increased allocations of stocks, particularly compared to most Taft-Hartley union plans, and also lower-rated bonds, including mortgage securities.

The 10-year IRS extension was scheduled to expire in 2015, coinciding with the nuclear solution of legislated benefits cuts that passed in December 2014.

This February, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) asked the Government Accountability Office to inform Congress on a series of concerns, among them:

- Was the allocation of Central States investments consistent with comparable pension plans that have managed to remain solvent?

- Has the Labor Department appropriately reviewed Central States’ decisions regarding changes in investment managers and strategies?

- Has Labor maintained proper oversight of a special independent counsel whose appointment was a condition of the 1982 federal consent decree that broke the grip of organized crime at the fund?

“While Central States is not the only multiemployer pension fund that is facing severe funding issues,” Grassley wrote, “what is unique is the role the federal government has played in the operations of the fund since at least 1982.” The consent decree, he noted, “granted DOL considerable oversight authority as to the selection of independent fund managers as well as changes in investment strategies. DOL was further granted oversight of a court-appointed independent counsel.”

As we await the government watchdog agency’s response, I aim to fill in some gaps never addressed during the limited public debate over the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act in late 2014. That law laid the historic groundwork to cut benefits at pensions deemed to be in “critical and declining status.”

Central States is considered to be a multiemployer plan because thousands of independent trucking companies paid into a shared retirement fund for union drivers. One problem with multiemployer plans is that as some employers went bankrupt, or otherwise shirked their obligations, the remaining employers faced larger liabilities, and the pensioners fewer funds.

Today, only three of the plan’s 50 largest employers from 1980 still pay into the plan. And for each active employee, it has 5.2 retired or inactive participants.

Labor Department investigators fought a heroic battle against corrupt trustees and mob influence decades ago, culminating in the 1982 consent decree to “assure that the fund’s assets are managed for the sole benefit of the plan’s … beneficiaries,” according to a July 1985 report by the Government Accountability Office. At issue then were more than $518 million in real estate loans involving “apparent significant fiduciary violations and imprudent practices,” the GAO said.

Under the decree, a new fiduciary—originally, Morgan Stanley—was granted “exclusive responsibility and authority to 1) control and manage the fund’s assets; 2) appoint, replace, and remove investment managers; 3) allocate fund investment assets … and 4) monitor the performance of all investment managers,” the GAO said.

Union officials and company executives who served as pension trustees were removed from investment decision-making, but that did “not diminish” their obligation “to monitor the performance of the fund’s investment managers, or relieve (them) of any (other) fiduciary liability,” the GAO said.

Instead, trustees were to be consulted when investment objectives or policies changed. Any such changes also had to be reported to the secretary of Labor and the independent special counsel, and ultimately be approved in federal court.

Rudy Giuliani, then the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, followed up Labor’s efforts with a racketeering lawsuit in 1988 to smash the “devil’s pact” between organized crime and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters that allegedly included mail fraud, embezzlement and murder.

In “one of the most ambitious lawsuits in U.S. history,” federal prosecutors helped expel more than 500 union officers and members, according to the legal scholars James B. Jacobs and Dimitri Portnoi. Yet the consent decree also had the effect of replacing a strong union hand at the pension with multiple layers of administrative, managerial and regulatory oversight, none with particularly strong incentives to protect the fund before, during, or after the financial markets crisis.

The Central States administrator itself “is not responsible for the fund’s asset allocation and management of the fund’s investments,” Executive Director Tom Nyhan told me. Rather, investments were the exclusive province of the fiduciaries—Goldman Sachs and Northern Trust during the crisis—who were vetted and approved by the Labor Department, under the consent decree. In turn, while Goldman Sachs and Northern Trust were paid a fee based on assets under management, they didn’t invest the portfolio directly but hired managers to do so.

And Labor Department spokesman Michael Trupo conveyed a statement that described the government regulator as rubber stamp, at best.

“The department’s role under the consent decree is limited to reviewing proposed trustees and named fiduciaries before they are appointed; [and] reviewing proposed changes to the investment policy statement prior to implementation,” Trupo said. “While the department may object to actions proposed or discovered in its review, the court order gives the department no role in the day-to-day operation or investment decision-making of the fund.”

One more layer

Still, that left one more layer to help safeguard the retirement plan: the special independent counsel who reports to the federal court under the 2002 consent decree. During the financial crisis, the special counsel was former federal judge Frank McGarr, who died in January 2012 at age 90 “after a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease,” according to his obituary. He’d tendered his resignation four months earlier but temporarily continued to fulfill the assignment.

McGarr’s reports are among the few public records available about how the pension and its fiduciaries wrestled with their finances. And these records are invaluable. But McGarr produced only three quarterly reports during the final year of his service, and there were other untimely lapses even though presiding Judge Milton Shadur credited the reports as “thorough,” “detailed” and meticulous”—so much so they “obviated any need for further questioning or commentary.”

When I asked Central States Executive Director Nyhan how vigorous the special independent counsel was during the later years, when the retirement plan came under such great financial stress, he replied, “I take great offense to your veiled accusation” that McGarr “was unable to fulfill his responsibilities because he was of advanced age and suffered from Parkinson’s disease. … Judge McGarr may have been suffering from Parkinson’s, but he was in no way infirm.”

In contrast, the late judge’s daughter, Patricia DiMaria, took no exception. “He was in a wheelchair, but mentally he was very sharp,” she told me.

What remains of the Central States fund clawed its way back in recent years, in part after Goldman Sachs resigned the account. But the unrecovered losses ensured that the fund would start over at a much smaller base, and be unlikely to ever close the huge gap in its unfunded liabilities. Today, only pensioners are to be held accountable. And that is why the long, torturous tale of this tragic fund should resonate for all Americans. No social safety net is secure without reliable guardians.

In response to Sen. Grassley’s questions to the GAO, I offer the following:

Q: Was the allocation of Central States investments consistent with comparable pension plans that have managed to remain solvent?

A: No. Central States’ portfolio allocation was about two-thirds stocks, and less than one-third bonds entering the 2008 financial markets crisis. That is much more aggressive than the 48% median allocation to stocks by all Taft-Hartley Union plans at the beginning of 2008; and well above the median allocation of 59% of Taft-Hartley plans with assets of more than $2 billion.

What’s more, Central States’ investment loss of 29.81% in 2008 exceeded the 25.9% loss of its median peer, as well as the 20.46% median decline of all Taft-Hartley plans, according to data prepared for MarketWatch by Wilshire Associates. And Goldman Sachs and Northern Trust each underperformed their investment benchmarks for the fund in at least three out of four years, from 2006 through 2009.

“Even skilled and prudent asset managers incur losses, and no asset manager or process can guarantee gains during every period during every set of market conditions. They were particularly challenging market conditions during 2008,” Goldman Sachs spokesman Andrew Williams told me. He said that Goldman Sachs produced overall positive returns from August 1999 to July 2010.

Northern Trust spokesman John O’Connell said that “to protect client confidentiality, Northern Trust does not discuss specific clients or details about their programs, including investment performance.”

Q: Has the Labor Department appropriately reviewed Central States’ decisions regarding changes in investment managers and strategies?

A: Labor spokesman Trupo replies: “While the department may object to actions proposed or discovered in its review, the court gives the department no role in the day-to-day operation or investment decision-making of the fund.”

I’m not sure that answers if Labor provided appropriate oversight but it does suggest that the government regulator was not very proactive.

Trupo also provided me with the statement that: “The chief problem facing the Central States plan has been underfunding. Trucking deregulation in the 1980s exacerbated the funding problem because of the dramatic contraction of the industry, and the accelerated number of contributing employer bankruptcies that rapidly and substantially reduced the fund’s contribution base. At the same time, those bankruptcies substantially increased the fund’s legacy costs with no foreseeable way to make up those lost contributions. These converging factors, rather than poor investment strategy or performance, were primarily responsible for the severe underfunding that the fund is now experiencing.”

Q: Has Labor maintained proper oversight of a special independent counsel whose appointment was a condition of the 1982 federal consent decree?

A: Trupo: “The special counsel is chosen by the court, not the department.”

This suggests that Labor did not provide active oversight.

Finally, Central States’ benefits-slashing application to Treasury says “the Trustees have taken all reasonable measures to avoid insolvency of the plan.” The request elicited about 2,800 comments to Treasury officials, and 5,500 more to the fund. On their behalf, and all 400,000 pensioners, I’d like to be sure of the answer.

“We are not bonus-receiving bankers riding the coattails of bad decisions asking for a bailout,” says David Maxey, a retired Teamster in Indiana, who faces a monthly benefit cut of half to $1,151 a month. “We are over 400,000 blue-collar Americans asking for some fair consideration. When this is scheduled to go into effect, I will be 68 years old. Walking a freight dock or driving a truck are not likely.”

This excellent analysis is the first of a two-part series on the Central States Pension Fund. The second part will look more closely into why its investment performance suffered.

I’ve already covered the withering of Teamsters’ pension and ended it on this sobering note:

[…] it’s high time the United States of America goes Dutch on pensions and follows the Canadian model of pension governance. Now more than ever, the U.S. needs to enhance Social Security for all Americans and implement the governance model that has worked so well in Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden (and even improve on it).

I know, for Americans, these are all “socialist” countries with heavy government involvement and there is no way in hell the U.S. will ever tinker with Social Security to bolster it. Well, that’s too bad because take it from me, there is nothing socialist about providing solid public education, healthcare and pensions to your citizens. Good policies in all three pillars of democracy will bolster the American economy over the very long-run and lower debt and social welfare costs.

If U.S. policymakers stay the course, they will have a much bigger problem down the road. Already, massive inequality is wiping out the middle class. Companies are hoarding record cash levels — over $2 trillion in offshore banks — and the guys and gals on Wall Street are making off like bandits as profits hit $11.3 billion in the last six months.

Good times for everyone, right? Wrong! Capitalism cannot sustain massive inequality over a long period and while some think labor will rise again as the deflationary supercycle (supposedly) ends, I worry that things will get much worse before they get better.

In our conversation last week, Ron Mock, CEO of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, expressed the same concerns when he reviewed the plan’s 2015 results:

“I worry about aging demographics and people retiring with no pension. We do our part in ensuring a small subset of the population has their retirement needs addressed for the future.”

Unlike the Central State pension fund, Chicago’s pension plan or most U.S. public pensions which are doomed, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and the Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan are both enjoying a funded status that most pension plans can only dream of.

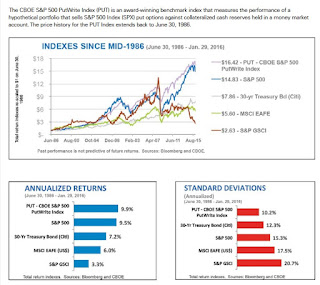

Let me go back to this pie chart that I posted when I went over Ontario Teachers’ 2015 results (click on image):

When people ask me why I’m such a stickler for large, well-governed defined-benefit plans, I point out charts like the one above to make my case. If you’re looking for a solution to the global retirement crisis, this is it, right there in that chart.

Yes, it’ true, Ontario Teachers and HOOPP do all sorts of sophisticated derivatives strategies to cleverly leverage up their portfolio, something which other pensions can’t do either because they lack the internal expertise or because laws prohibit them from leveraging up their portfolio.

But this isn’t the main factor which explains their funded status relative to most U.S. or even Canadian plans. The two main factors which explain the outperformance of Ontario Teachers’ and HOOPP are:

- Good governance that allows them to attract and retain qualified investment managers to manage assets internally at a fraction of the cost and

- A shared risk model that allows them to sit down with their stakeholders to implement conditional inflation protection (or other options) if the plan becomes underfunded.

And by the way, it’s not just Ontario Teachers and HOOPP that are fully funded in Canada. In Ontario, for example, other smaller plans which adopted a shared risk model like CAAT and OPTrust are also fully funded plans.

And even though I highlighted problems with some Canadian corporate plans getting hit by the loonie, the reality is most Canadian pension plans are in far better shape than their U.S. counterparts because they got the governance right and implemented a shared risk model.

By the way, following my last comment, I received an email from Bernard Dussault, Canada’s former Chief Actuary, stating the following:

The solvency basis for the valuation of defined benefit pension plan liabilities, which is dictated by accounting standards, portrays a distorted and inaccurate picture of most, if not all, DB plans financial status because it requires that the assumed long term yield on the plan fund be set equal to the current average market interest rates rather than the realistically higher projected yield on the fund.

Indeed, pension funds portfolios are normally much diversified among equities, infrastructures, real estate, etc., and generally comprise only a relatively small proportion of interest bearing vehicles such as bonds.

Therefore liabilities are, through the solvency valuation basis, unrealistically:

- overestimated when interest rates are low, thereby unduly overestimating the plan’s debt;

- underestimated when interest rates are high, thereby unduly overestimating the plan’s surplus.

In other words, DB plans financial status is actually not too bad on average and far from as bad as revealed by solvency valuations when interest rates are low. And it would be quite OK rather than not too bad if federal and provincial pension-related legislation would once and for all fully prohibit contributions holidays after a plan experiences a surplus.

I agree with Bernard on prohibiting contribution holidays once and for all and he makes an excellent point that the solvency basis for determining the valuation of a DB plans distorts the funded status of a plan, but bonds are still the measure of risk-free assets and all other assets are valued in relation to bonds (listen to Bill Gross explain it here).

Moreover, it all depends on where pension plans are currently valued. When I discuss Canadian DB plans that are 80% funded, I’m not as worried as when I discuss U.S. DB plans that are 60%, 50% or 40% funded.

In other words, the current funded status matters a lot. The starting point matters and as Ron Mock and Jim Keohane keep reminding me, all pensions are path dependent, which means they can’t sustain a big drop in their assets, especially when rates are at historic lows and deflation is knocking on our door. This forces public pensions to pile on risk after a huge drawdown in the hopes of regaining fully funded (or more likely, 80% funded status) and that’s the last thing they should be doing, especially if they are a mature plan paying out more in benefits than they receive in contributions.

Look at what happened to the Central States Pension Fund. It’s a textbook example of bad governance, gross mismanagement and terrible investment decisions. And it’s going to be workers and pensioners who will bear the brunt of years of gross negligence.

Of course, the sharks on Wall Street couldn’t care less. They are there to bleed these public pensions dry. They routinely gouge pensions on fees on structured products, hedge funds, private equity funds, currencies, commodities, derivatives, you name it. If they can collect a big fat fee or spread by”ripping their face off”, they’ll do it and they couldn’t care less about millions retiring in pension poverty.

And to add insult upon injury, you have a hedge fund legend and maestro central banker warning us of the looming catastrophe linked to entitlement spending run amok (never mind the facts or that productivity is grossly understated or that trillions are parked in offshore accounts). Nope, go after grandma and grandpa and screw workers by cutting their Social Security benefits.

All this to say while the movies love vilifying the mob, it’s the legalized mob on Wall Street that should concern you because while most Americans are going to retire in poverty, the financial parasites on Wall Street will always find ways to make off like bandits no matter how poorly pensions and 401(k)s are doing.

Photo by Dirk Knight via Flickr CC License