The official analysis of a proposed public pension initiative issued last week said “likely large savings” in retirement benefits would be offset by pressure for higher pay and other costs.

But the analysis does not estimate whether it would be a net gain or loss for government employers.

The initiative would open the door for what supporters of state and local government pensions have long feared — a switch to 401(k)-style individual investment retirement plans widely used by private-sector employers to avoid long-term debt and investment risk.

The basic clash, well known by now, is whether pensions are too generous, take money needed for basic services and will be “unsustainable” in the long run or, to the contrary, are affordable, manageable if correction is needed, and necessary to have quality government workers.

The initiative is based on a simple concept: For new state and local government employees hired on or after Jan. 1, 2019, require voter approval of their pensions and of government paying more than half the total cost of their retirement benefits.

Other provisions taking effect immediately for current workers would require voter approval of increased pensions and give voters the right to set their pay and retirement benefits.

But nothing simple about how the initiative would play out was found in the fiscal analysis sent to Attorney General Kamala Harris by nonpartisan Legislative Analyst Mac Taylor and Gov. Brown’s finance director, Michael Cohen.

The attorney general is expected to issue a title and summary for the initiative by Aug. 11. Two previous pension reform initiatives were dropped after the sponsors said Harris gave the measures inaccurate and misleading summaries, making voter approval unlikely.

The process that would be set in motion by passage of the proposed initiative has “significant uncertainty,” said the 11-page analysis

“Significant effects — savings and costs — on state and local governments relating to compensation for employees,” said the summary of fiscal effects. “The magnitude and timing of these effects would depend heavily on future decisions made by voters, governmental employers, and the courts.”

One certain effect is a major battle with public employee unions, if a bipartisan coalition led by former San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed and former San Diego Councilman Carl DeMaio gathers enough signatures to put the initiative on the fall ballot next year.

Reed and DeMaio led successful pension ballot measures in their cities, approved by two-thirds or more of voters. But several attempts to put a pension initiative on the statewide ballot have failed, including one by Reed and others last year.

The analysis of the new proposed statewide initiative said: “In the absence of voters approving the continuation of existing pension plans in a ballot measure — the measure closes existing governmental defined pension plans on Jan. 1, 2019.”

Voters also could be asked to approve a different pension plan for the new hires. But the authors of the initiative have said government employers would not need voter approval to offer new hires a 401(k)-style plan.

In the view of some supporters, the proposed initiative would, for new government hires, make the 401(k)-style retirement plan the “default,” the term for a preset option in the computer world.

It’s not clear that voters and government employers would want to end pensions for all new hires. In San Diego, for example, police were exempted in a pension initiative that switched new hires to 401(k)-style plans.

In a section labeled “Likely Large Savings Related to Retirement Benefits,” the analysis of the proposed initiative said some new hires are not expected to get pensions, then goes on to say in a following section that the 401(k)-style plan is most likely to replace a pension.

“Under this measure, defined benefit pension plans would not be available to new employees unless specifically authorized by voters,” said the analysis. “As such, it is likely that such benefits would be reduced or eliminated in many jurisdictions.”

Employees transferring from other government employers would receive the same retirement plan as the new hires, ending the “reciprocity” agreements that currently allow transfers with little or no change in pensions.

If voters approve a new pension plan for new hires, instead of continuing the current one, employer costs would be lower because new employees would be expected to pay half the pension and retiree health care cost, including the “unfunded liability.”

Currently, employer pension contributions often are two or three times larger than employee contributions. Only the employer is responsible for the “unfunded liability” resulting from investing shortfalls, demographic changes or retroactive pension increases.

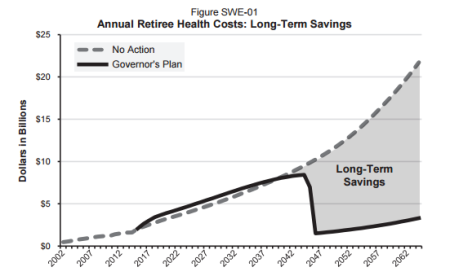

Retiree health care often is pay-as-you-go with no pension-like investments to help pay future costs. Most state workers contribute nothing to a retiree health care plan that is more generous than the plan for active workers.

Offsetting the savings, said the analysis, likely would be pressure to raise pay and other compensation to attract and retain employees offered less generous pension and retiree health plans.

Higher wages increase Social Security and Medicare costs. Employers are likely to contribute to 401(k)-style plans. Some employees may be moved into Social Security, where employers and employees each contribute 6.2 percent of pay.

Disability benefits are likely to continue, particularly for police and firefighters. The costs could go up if new hires receiving lower retirement benefits continue working to an older age.

Another increased cost, said the analysis, is that as a closed pension plan “winds down” over the decades, with fewer members and less time to recover losses, pension boards are likely to shift to less risky investments, yielding lower returns.

If plans are closed to new members, the California Public Employees Retirement System is required by state law to terminate the plan, triggering a large payment to cover the pensions promised plan members.

The termination fee has been called a “poison pill” that prevents employers from switching to 401(k)-style plans. When Villa Park asked to close a 30-member CalPERS plan, seven active, the fee was $3.7 million, far too much for the small city to pay.

The initiative addresses this problem by requiring voter approval of termination fees and other plan closure costs. But the initiative analysis said the “full extent” that this provision would limit pension board power is not clear.

An early and important legal dispute between the initiative sponsors and a union coalition is over the provision giving voters the right to set pay and retirement benefits: Would it allow pensions earned by current workers in the future to be cut or eliminated?

Under the “California rule,” a series of state court decisions are widely believed to mean that the pension offered on the date of hire becomes a “vested right,” protected by contract law, that can only be cut if offset by a comparable new benefit.

Most pension reforms have been limited to new hires. But cutting pensions current workers earn in the future, while protecting amounts already earned, would get the immediate savings sought by those who say rising pension costs are starving other programs.

“Many of the measure’s provisions could be subject to a variety of legal challenges,” said the initiative analysis. “For instance, it is not clear to what extent allowing voters to use the power of initiative or referendum to determine elements of compensation for existing employees would change governmental employers’ contractual obligations under the California rule.”

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.