This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Jacqueline Nelson of the Globe and Mail reports, Ontario Teachers posts 11.8% return in 2014, looks abroad for investments:

The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan is looking abroad for investment opportunities after posting strong returns in 2014.

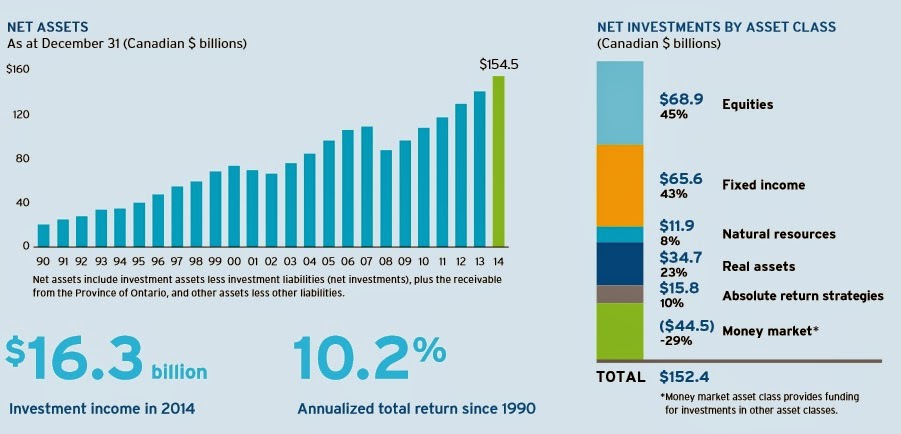

The pension plan, which invests on behalf of 311,000 teachers and retirees in Ontario, earned an 11.8-per-cent return on its investments last year and saw its assets grow to $154.5-billion, up from $140.8-billion a year earlier.

This is the second year that Teachers has posted a surplus after a decade of recording annual deficits, with funding levels at 104 per cent at the end of 2014. The plan has $6.8-billion of surplus assets above the estimated liability for providing pensions to members.

Teachers has posted an annualized 10.2-per-cent rate of return since its founding as an independent organization 25 years ago.

The pension plan achieved the results despite turbulent market conditions including the drop in oil prices, a competitive private investment environment and economic uncertainty in Europe, said Ron Mock, chief executive of Teachers, in a press conference announcing the results. And in the past four to five months, Teachers has been re-evaluating its investment strategy with an eye on the coming decade, he said.

“The global environment, the investing environment and quite frankly the sovereign wealth [and] pension environment has changed substantially in the last five to seven years,” Mr. Mock said. “So having a strategy that’s global … and in our case long, long-term investing, is critically important.”

The 2014 financial results included a 13.4-per-cent return on equities and a 22-per-cent return on private capital investments. The fund’s fixed income portfolio, including bonds, had a one-year return of 12 per cent, while the real estate group earned 11.1 per cent, and infrastructure earned 10.1 per cent.

Teachers plans to “adapt and modify” its strategy to include looking for more investment opportunities around the world and building up assets in its target regions. “Teachers will need to have global capabilities in the coming years,” Mr. Mock said.

“In 2014, we also spent time growing our global footprint,” said Neil Petroff, chief investment officer at Teachers. After opening a new Hong Kong office in 2013, Teachers spent the past year hiring more local staff and will look to do more deals in the region.

Late last year, Teachers said it would build out its London office, which opened in 2007 and now has a portfolio of assets worth $22-billion. Major investments in 2014 include buying the half of Bristol Airport it didn’t already own in September, and increasing its stake in Birmingham Airport.

“As we look at our global expansion, we’re a little different than the average fund. We don’t open an office and say let’s go find assets,” said Mr. Petroff, who plans to retire in June of this year. Instead, Teachers would look to establish offices in regions where it has holdings. The next logical move for an office might be South America, said Mr. Petroff, where Teachers has a “critical mass of assets” in several countries.

Still, Teachers plans to keep its bottom-up investment strategy, which eschews thematic investing in favour of analyzing individual stocks.

These evolving investment goals come as the average age of plan members has been steadily increasing since the 1970s, from an average expected mortality rate of 79 to 90 years of age for women. The majority of Teachers members are women, who tend to live longer than men.

Right now, Teachers has 182,000 active members and 129,000 pensioners, but the pensioner population is catching up quickly to working teachers, said Tracy Abel, senior vice-president of member services, noting that 135 of the plan’s pensioners are over the age of 100.

Madhavi Acharya-Tom Yew of the Toronto Star also reports, Teachers’ pension plan posts 11.8 per cent return:

The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan posted an 11.8 per cent return for 2014, even as falling oil prices took a bite out of its investment portfolio.

Investment earnings for the year were $16.3 billion, up from $13.7 billion in 2013, the pension fund said on Tuesday.

The strong performance puts the defined benefit pension plan in a surplus position for the second year in a row – it’s currently 104 per cent funded – with its net assets under administration reaching a record $154.5 billion.

“Navigating ourselves through these waters is not an easy task,” president and chief executive officer Ron Mock told reporters at a media conference at Teachers’ head office in North York.

“With continuing low interest rates, intense competition pushing up asset prices, the slide in oil prices and resulting stock market-volatility, 2014 was not an easy year for investment success.”

The pension fund said its managers outperformed the consolidated investment benchmark of 10.1 per cent, adding $2.4 billion in returns to the plan last year.

The pension fund invests on behalf of 311,000 active and retired teachers in Ontario. It has an annualized rate of return of 10.2 per cent since its inception 25 years ago.

The value of the plan’s public and private equity investments reached $68.9 billion as of year-end, up 13.4 per cent from the prior year.

Investments by Teachers’ private capital arm rose 22 per cent last year and the plan’s fixed income holdings rose by 12 per cent.

Investments in natural resources were down 19.4 per cent for the year, executives said.

“The silver lining of this natural resource performance is that commodities are a very small allocation. It hurt our returns, but not very much,” chief investment officer Neil Petroff told reporters.

Energy accounts for six per cent of the plan’s public equity portfolio, and four per cent of its private capital holdings, according to the annual report.

The plan’s expense rate is a miniscule 0.28 per cent. The average Canadian mutual fund has a management expense ratio of about 2 per cent.

Investment returns account for more than three-quarters, about 78 per cent, of the pension payouts that teachers receive in retirement. Member contributions account for 10 per cent and the Ontario government, as their employer, contributes 12 per cent.

The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan is a defined benefit plan, meaning that the payouts that members receive in retirement are a set or “defined” amount, based on their salary and length of service. Investment decisions, and risks, are assumed by the plan.

Teachers’ has recently invested in GE Aviation, XPO Logistics, and PODS, a company that provides portable, on-demand moving and storage containers. It has also made investments in airports in Birmingham and Bristol, and Premier Lotteries in Ireland.

The plan opened an office in London in 2007 and another in Hong Kong in 2013. It expects to open a new one in South America, where it has investments in logistics firms, and water treatment plants, in the coming months, executives said.

The average age of a retiree who is collecting a pension from Teachers’ is 70. The average age of its active members is 42. The plan has 182,000 active members and 129,000 pensioners.

“Our pensioner population is catching up quickly to the working teacher population,” Mock said.

The pension plan currently has about 130 pensioners over the age of 100. On average, retirees are expected to collect their pension for 31 years.

Petroff told reporters that his 82-year-old mother, who is a retired teacher, receives a pension from the plan. “Every year she calls me and says, ‘You’re doing a wonderful job, Neil. Keep it up.’”

Petroff is retiring from the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan on June 1, the pension fund manager announced this week. There will be an internal and external search for a successor.

Indeed, Neil Petroff is retiring on June 1st and Ron Mock told me the plan has launched a global search to find a new CIO.

You can read a lot more on Ontario Teachers’ 2014 results on their website by clicking here. I highly recommend you read the 2014 Annual Report as well as the Report to Members.

I had a long chat with Ron Mock, Ontario Teachers’ President and CEO, late last week to discuss their 2014 results and dig a lot deeper into how they invest in an increasingly more competitive climate.

Below, I provide you with bullet points on our conversation:

- We began by talking about liabilities which are at the heart of every investment decision Teachers undertakes. Ron told me the board sets the discount rate which is mostly determined on mark-to-market basis (keep in mind, the Oracle of Ontario has one of the lowest discount rates in the world and unlike U.S. public pensions, their discount rate isn’t marked-to-fantasy). Once the board sets the discount rate and determines the plan’s liabilities, the sponsors (the government of Ontario and the Ontario Teachers’ Federation) then set the contribution rate and adjust benefits according to he plan’s funded status.

- In 2010, the plan removed full inflation protection and introduced 60% inflation protection to return it to fully funded status. As Jim Leech, the former president and CEO, noted back then, the liabilities were due to the maturation of the plan. The main driver of liabilities back then was the drop in interest rates, which significantly reduced bond yields and increased liabilities. In the early 1990s, real-return government bonds (RRBs), the backbone of the plan, generated a fixed 4.5% return plus inflation. These rates of return fell down to 1.6% four years ago – closer to historic averages – which meant the plan needed more money then to pay out future liabilities. They have since fallen to near zero percent, adding even more pressure on the plan to find suitable alternatives to match their long duration liabilities. Every decrease of one percentage point in interest rates increased the cost of a pension plan by 20% in 2010 and it hasn’t gotten any better since then. Ron told me the liabilities now swing by $30 billion every time rates go down by 100 basis points (1 percent) and their duration is 22.

- Adding to OTPP’s challenges is the fact that there are now only 1.4 working teachers for every retiree, and higher life expectancies for their members (ie. more longevity risk). As Ron explained to me, “this means there are fewer active members to absorb a substantial loss” and since members are living longer and the average age of their members is rising, they need to make sure their risk-adjusted returns remain extremely high and that they mitigate against any potentially devastating loss, like 2008 which rattled the plan.

- Ron explained how critical “path dependence” is to their plan: “When you have 10 active members for every one retiree, you can absorb a $100 loss much easier by increasing the contribution rate and spreading that loss among the active members. But when you have almost as many retirees as active members, you simply can’t afford to sustain a huge loss and because it will significantly impact the cost of the plan and endanger benefits to members.”

- Ron also said that the base case for the contribution rate is 11%, meaning the sponsors don’t want to see huge volatility in returns which will potentially mean a substantial increase in the plans’ liabilities and the contribution rate. “Our job is to minimize the volatility of that contribution rate and keep it stable for as long as possible and the sponsors can use inflation protection as a relief valve to moderate the plan according to its funded status. For a plan to be sustainable, it needs to be flexible and the sponsors need to share the risk of the plan.” He added: “Now that the plan is fully funded, the sponsors have the option to restore full inflation protection to the plan’s members.”

- Because of the long duration (22) of the plan’s liabilities and the fact that they simply can’t find enough real returns bonds (RRBs) to match these liabilities, it forces them to swap into Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) to make up for this scarcity. But even that’s not enough because there is a duration mismatch and lack of available product so they’re increasingly looking at better matching all their public and public assets with their liabilities to deal with the plan’s sensitivity to rates, especially on the downside.

- This is where our conversation shifted to asset allocation and how it relates to liabilities. Ron said that bonds serve three functions: 1) they provide a negative correlation to stocks; 2) they provide return and 3) they move opposite to their liabilities. “If rates go up, our liabilities decline by a lot more than the value of our bond portfolio, which is exactly what we want to maintain the plan fully funded.”

- As far as illiquid assets, Ron said that in real estate Teachers looks for class A malls and office buildings and doesn’t invest in hotels, strip malls, pure condo buildings, or box stores. “The lease of a hotel is one day. We prefer long term leases of ten years with stellar clients such as well known retailers or office tenants like top law and accounting firms.” He added: “Because our liabilities are in Canadian dollars, we have a substantial exposure to Canadian commercial real estate but are also looking in the United States for similar class A real estate because there aren’t enough opportunities up here.” Teachers isn’t alone, many other large Canadian pensions have been busy snapping up U.S. real estate and given my outlook for Canada, I think is is a wise move.

- In infrastructure, he told me that Teachers and OMERS own high speed trains in Europe and there too, they are looking for quality assets that can provide steady returns for a very long time to match their long dated liabilities. Interestingly, Ron said that many pension and sovereign wealth funds are jumping into infrastructure paying top prices and they don’t have people with operational experience to manage these assets (a buddy of mine in infrastructure totally agrees and says a day of reckoning awaits all these large funds with investment banking types looking to strike their next infrastructure deal). Ron told me that “Teachers’ infrastructure team sticks closely to its pricing discipline even if that often means walking away from an asset they’d really like to own. We also make sure we have board members with operational experience in each of our infrastructure investments.”

- In private equity too, Teachers is looking for long term deals that can yield nice returns over a very long period. Ron cited the example of the Irish lottery and other deals that they entered looking for solid returns over a long period.

- In fact, across, public, private and hedge fund assets, Teachers is looking for “the highest Sharpe ratio” in order to match their assets and liabilities as closely as possible. Even in public equities, they moved more into utilities last year to better match assets with liabilities.

- One area where Teachers got whacked again in 2014 was in natural resources, down 19% mostly due to the poor performance of their passive commodities exposure. I will discuss this below but Ron explained to me that they’ve implemented a Bridgewater type “all-weather portfolio to deal with four economic cycles, including an inflationary environment where commodities outperform” (Teachers has a substantial investment in Bridgewater’s Pure Alpa fund).

- Our discussion inevitably shifted to benchmarks and compensation. Ron told me their benchmarks are constructed with liabilities in mind and the risks they take in each investment portfolio are closely monitored by the board to make sure they’re in line with the accepted risk parameters. “You won’t see us take opportunistic real estate bets to beat our real estate benchmark.” Maybe not, but whenever I see any Canadian pension fund trouncing its benchmark in any asset class (like Teachers did in real estate and infrastructure in 2014), my antennas immediately go up and I start wondering whether those benchmarks accurately reflect the risks of the underlying investments (admittedly, over the last four years, which is what compensation is based on, the outperformance isn’t as stark in either asset class).

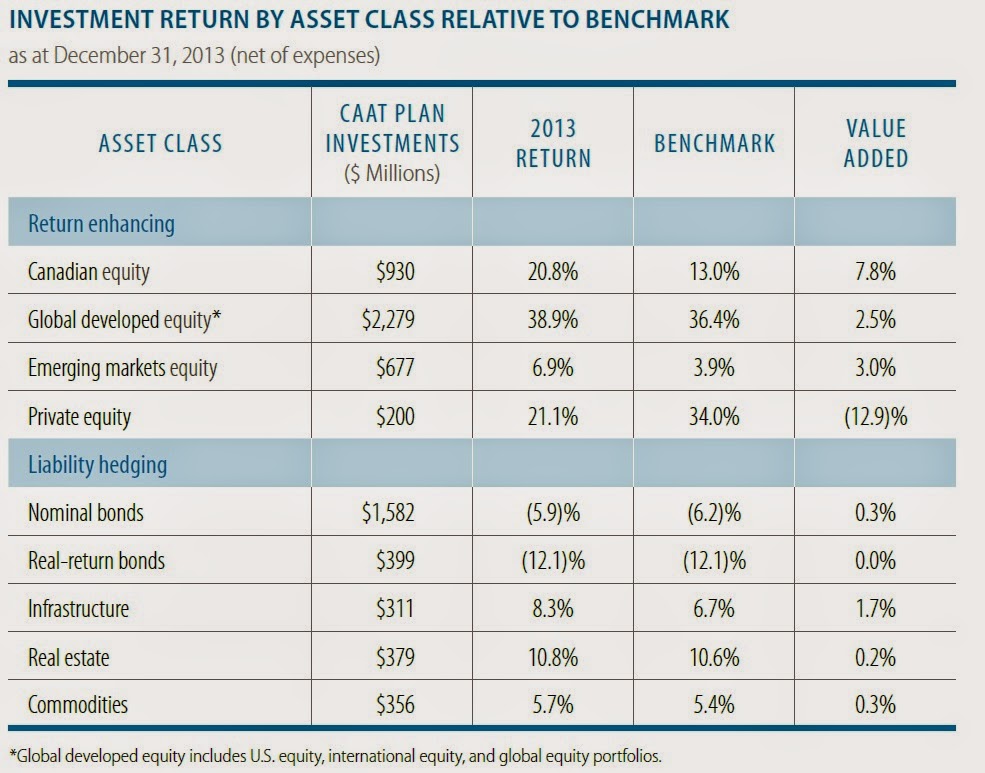

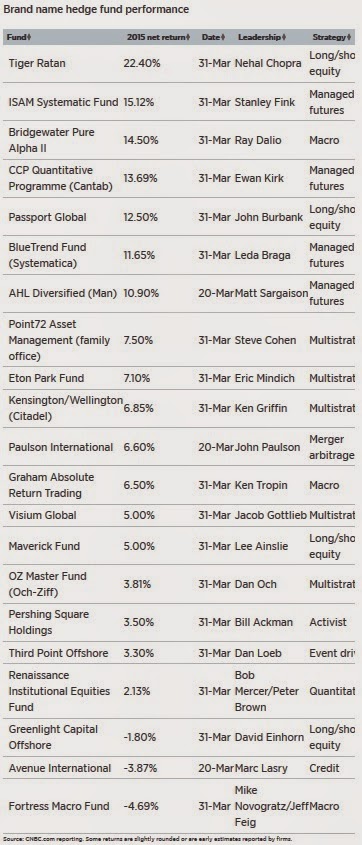

In fact, I want you all to click on the image below (page 13 of Annual Report):

You can scan the results of broad asset classes over the last year and four years. Unlike other large Canadian pensions, Teachers embeds private equity in its Equities asset class, making it harder to determine how much of the outperformance in non-Canadian equity is due to value-added in private as opposed to public markets (my hunch is it’s almost all due to private equity since one of the articles above states Teachers’ private capital arm rose 22% last year).

Also, you will see how well real estate and infrastructure performed over the last year and four years. Note the strong outperformance over the benchmarks of these assets in 2014, mostly due to higher valuations as everyone is jumping on the real estate and infrastructure bandwagon. Over the last four years, the outperformance in real estate isn’t as strong as that of infrastructure.

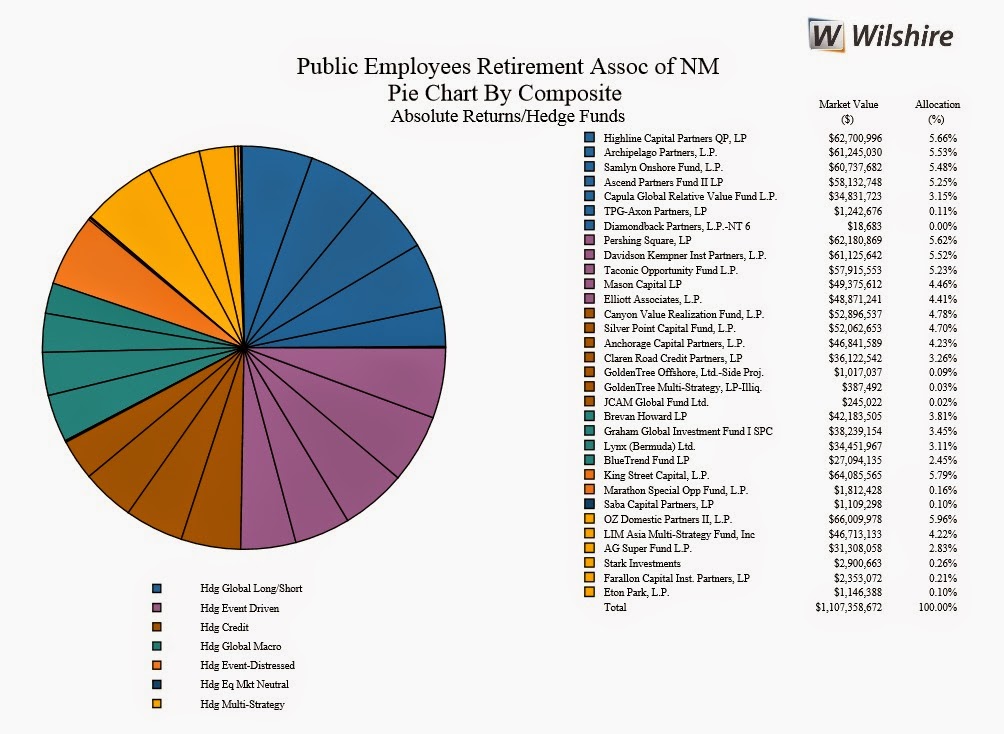

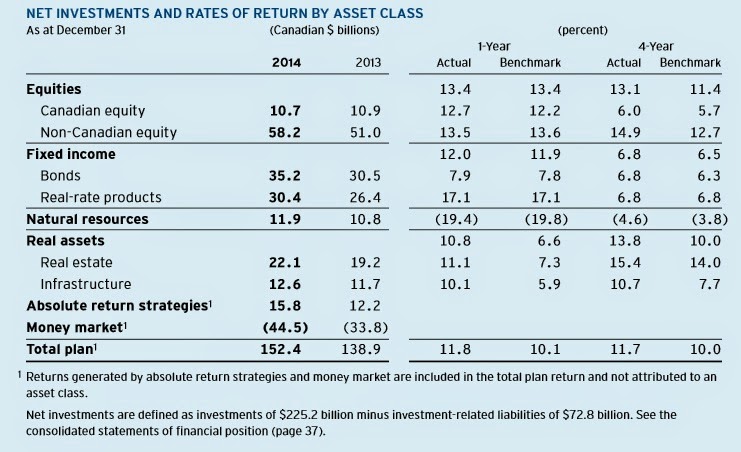

One big area of investments which isn’t discussed (deliberately) in detail in the Annual Report is hedge funds. Teachers invests a substantial amount in external hedge funds and engages in internal absolute return strategies. From page 17 of the Annual Report:

Teachers’ uses absolute return strategies to generate positive returns that are constructed to be uncorrelated to the returns of the plan’s other assets. These strategies are executed primarily by the Tactical Asset Allocation and Fixed Income & Alternative Investments teams. Internally managed absolute return strategies generally look to capitalize on market inefficiencies. The plan also uses external hedge fund managers to earn uncorrelated returns, to access unique strategies that augment returns and to diversify risk. Assets employed in absolute return strategies totalled $15.8 billion at 2014 year end compared to $12.2 billion the previous year.

I have discussed Teachers’ hedge fund strategy in great detail here and here. A brief recap for those of you who never read those comments:

Ron started the meeting by stating: “Beta is cheap but true alpha is worth paying for.” What he meant was you can swap into any index for a few basis points and use the money for overlay alpha strategies (portable alpha strategies). His job back then was to find the very best hedge fund managers who can consistently deliver T-bills + 500 basis points in any market environment. “If we can consistently add 50 basis points of added value to overall results every year, we’re doing our job.”

He explained to me how he constructed the portfolio to generate the highest possible portfolio Sharpe ratio. Back then, his focus was mainly on market neutral funds and multi-strategy funds but they also invested in all sorts of other strategies that most pension funds were too scared to invest in (strategies that fall between private equity and public markets; that changed after the 2008 crisis). He wanted to find managers that consistently add alpha – not leveraged beta – using strategies that are unique and hard to replicate in-house.

You can view some of the key hedge fund and private equity partners Teachers’ is engaged with on page 70 of the Annual Report (click on image):

On this list you will see familiar names in private equity and hedge funds, but they don’t print a full list of their partners like CPPIB and this is done deliberately to maintain capacity and a competitive advantage over their peers (I personally think they should be forced to disclose all their private equity and hedge fund relationships).

Which hedge funds does Teachers invest in? A lot of well-known multi strategy hedge funds (Citadel, Farallon, Millennium, etc.) I cover in my quarterly updates as well as market neutral funds, but also big players like Bridgewater and AQR. Unlike other pensions, however, Teachers puts most of its external hedge funds on a managed account platform managed by Innocap (where they used their size to squeeze the fees down to a ridiculous level but they are their biggest client by far).

Interestingly, Teachers recently announced it will be an anchor investor in Deimos Asset Management, a new hedge fund led by a group that includes a former Co-CEO of RBC Capital Markets. Deimos said it plans to develop a suite of alternative asset management products, which is expected to include a multi-strategy hedge fund, along with a wide variety of individual hedge fund strategies.

The fact that Teachers seeded this fund is a very strong endorsement and shows you they’re not afraid to enter into deals where others are typically running scared. In my opinion, far too many pensions are too focused on brand name funds and not paying enough attention in seeding emerging managers. In Quebec, the Caisse and other smaller pensions bungled up seeding emerging hedge fund managers through the SARA fund (it’s hemorrhaging money) to the point where Fiera Capital, Hexavest and AlphaFixe Capital had to step in and set up a $200 million fund to seed emerging managers (it remains to be seen how this new venture will work out but I know of one activist manager who is by far the best manager to seed in Canada).

Apart from absolute return strategies, the big money at Teachers is still coming from private equity. In fact, Teachers just announced it is exploring a sale or initial public offering of $2 billion of Alliance Laundry, a commercial laundry-equipment maker:

Based in Ripon, Wisconsin, Alliance Laundry says it’s the world’s largest designer and manufacturer of commercial laundry equipment with brands including Speed Queen and UniMac. Ontario Teachers’ bought the company from Bain Capital Partners in 2005 for $450 million.

Alliance expanded its reach across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia through the 2014 acquisition of Gullegem, Belgium-based Primus Laundry Equipment Group. Alliance reported revenue of $726 million in 2014, up 32% from the previous year, company filings show. It had net income of $29 million for the year.

Ontario Teachers’ also owns a 30% stake in coin-operated laundry machine provider CSC ServiceWorks Inc.

Do the math. Buying a company in 2005 for $450 million and selling it for $2 billion (assuming the deal goes through) is a nice juicy return of more than 3X their initial investment in ten years. And we’re not talking about sexy high-flying hedge funds here. This is a boring company which designs and manufactures commercial laundry equipment. And by doing this deal directly, Teachers saves huge on fees.

It’s this type of internal active management which allows Ontario Teachers to deliver exceptional results over a ten-year period at the lowest possible cost, far lower than any mutual fund and most of their peers (28 basis points of operating costs), with exception of HOOPP, which also delivered exceptional results in 2014 at a fraction of the cost of its peers and mutual funds.

Interestingly, Ron Mock praised all his peers, including HOOPP’s Jim Keohane which he called “brilliant,” but he rightly noted that if HOOPP was as big as OTPP, it too would be forced into managing more of its assets externally and would have “a hard time maintaining such a large fixed income allocation.”

Something else Ron mentioned is unlike most of his peers, which focus all their attention on investments, Teachers is a pension plan which manages assets and liabilities. “Every day we’re fielding calls from members to discuss a death of spouse, a divorce, or something else and we take this service extremely seriously which is why CEM voted us number one again in this area.”

Now, as you can see below from page 28 of the Annual Report, the senior managers at Teachers are compensated extremely well, so don’t shed a tear for them (click on image):

You will also notice that Neil Petroff, who is retiring in June, was the highest paid senior executive at Teachers with a total compensation of $4,481,846, which was even more than Ron Mock’s total compensation of $3,783,039. Ron explained to me that Neil has been working as a CIO for a long time which is why his compensation is higher.

These payouts are hefty by any measure, especially considering their members are Ontario teachers who get paid a modest income for their hard work, but it’s all part of the Canadian governance model which pays senior public pension executives extremely well (some argue outrageously well).

I’m not going to comment on compensation at Teachers except to say that they have delivered a stellar 10.2% annualized return since its founding and added billions over their benchmarks using internal active management which reduces costs and fees. On the topic of benchmarks, however, I did notice they were excluded from the Annual Report, which is odd and downright stupid, but a complete list of benchmarks is available at otpp.com/benchmarks.

Why are benchmarks important? There are a lot of reasons but the primary one is benchmarks determine value-added and compensation. Even after reading Teachers’ benchmarks, I still don’t understand what benchmark is used to gauge the risks and performance of private equity because it’s embedded under all equities.

In other words, you have to rely on the board of directors to make sure they are doing their job in setting up proper benchmarks for each and every investment activity. Now, I know enough about Jean Turmel, Teachers’ new chair of the board and formerly the board member overseeing all investments, to know he’s not a pushover when it comes to gauging risks and investments. Far from it, you’re not going to pull a fast one on Turmel who is obsessed with mitigating downside risk (sometimes too much so to the point where he doesn’t take enough risks!).

But I do wish Teachers had a section on benchmarks in their Annual Report, explaining in detail how they are determined by the plan’s liabilities and reflect the risks, leverage and beta of all investment activities including private equity and hedge funds.

Importantly, all Canadian pension funds and plans need to do a much better job on explaining how their benchmarks are determined, how they accurately reflect the risks of all investment portfolios, and how they link into compensation. If you want to get paid big bucks based on four-year rolling returns, it’s the least you can do!

Let me end by wishing Neil Petroff a happy retirement and all the best in whatever he decides to do post Teachers. Neil, like his predecessor Bob Bertram, is an exceptionally gifted investment professional with deep knowledge of private, public and hedge fund investments. He convinced Claude Lamoureux to hire Ron Mock to run Teachers’ hedge fund investments and the two men are close friends and have mentored each other in their respective roles at Teachers.

Two of my best blog comments featured Neil Petroff. One was a conversation with Neil on OTPP’s active management back in April 2011 where he discussed Teacher’s opportunistic approach (hope they got out of TransOcean and other drillers long before I warned my readers to short them!) and another was when I visited Toronto with Yves Martin who was looking for seed capital for his commodity fund (which unfortunately subsequently closed due to poor performance in a very tough market for commodities).

I told Neil straight out that I didn’t believe in passive commodities exposure and even recommended against it while working at PSP Investments (saving them a bundle but they fired me after ignoring my dire and timely warnings on the U.S. housing/ credit bubble which ended up costing them billions). I believe even less in passive commodities exposure now that global deflation is a very real possibility.

All this to say that I question why Teachers, a Canadian pension plan with tons of passive exposure to commodity shares and whose liabilities are in Canadian dollars (a petro currency) needs to have such a passive exposure to commodities (better off investing in guys like Pierre Andurand).

And before I forget, my favorite Neil Petroff quote to me: “If U.S. public pension funds used our discount rate, they’d be insolvent!!”.

A final word to Mr. Turmel. In our last conversation, you questioned whether a guy with Multiple Sclerosis can handle the pressure of trading. I know it came from a good place but without realizing it, that is the exact discriminatory mindset which infuriates me and makes me excel in my blogging and trading. I am happy to report that my health is stable and my personal investment performance over the last couple of years, playing the biotech and buyback bubbles, is doing a lot better than your old fund where my former PSP boss, Pierre Malo, also worked and even better than many top funds I regularly track.

You see Mr. Turmel, I might have MS and be blacklisted by every major financial institution in Quebec and Canada — because racist institutions that ignore diversity at the workplace refuse to hire someone with a chronic condition and an outspoken blog — but I’m still the best damn pension and investment analyst in the world and comments like this one prove it. So do me a favor, instead of propagating myths on people with disabilities, try hiring them at Teachers and elsewhere, you might be pleasantly surprised by their incredible work ethic and invaluable contributions.

As for the rest of you, including my old buddy out in Victoria, British Columbia, get to it and donate and/ or subscribe to this blog. If you’re taking the time to read my comments, please join others and take the time to support me through your financial contributions via PayPal at the top right-hand side under the click my ads picture.

Better yet, set your prejudices aside and hire me at your organization (LKolivakis@gmail.com). I’m a tough, cynical and sometimes hopelessly arrogant Greek-Canadian who loves Montreal and the Habs, but I guarantee you that you won’t find a better all-round pension and investment analyst who will work harder than anyone else to prepare you for the risks that lie ahead.

Below, Ontario Teachers’ CEO, Ron Mock, discusses 2014 results on BNN. I didn’t particularly like this interview because it was too short and there were some stupid questions asked (“why are you a major holder of BlackBerry shares“?!?) but I liked Ron’s explanation on the importance of bonds in their portfolio from an asset-liability standpoint.

Let me end by thanking Ron Mock for taking the time to chat with me in-depth on Ontario Teachers’ 2014 results. Ron, you’re a gentleman and a scholar and your insights provide me with a tremendous amount of food for thought. Keep up the great work and always strive to make Teachers’ an even better organization than it already is. If there are any errors in this comment or any additional comments you or others would like to make, please let me know and I will edit it.