Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Andre Tartar and Jill Ward of Bloomberg report, Brexit’s Biggest Fans Face New 115 Billion-Pound Pension Hole:

Turning 65 in the U.K. used to mean mandatory retirement and a future of endless holiday. But in 2016 it has come to signify a very different cut-off: membership in the single most pro-Brexit age group in the June 23 European Union referendum.

About 60 percent of Britons 65 and older voted to leave the world’s largest trading bloc in the recent vote, the most of any age group, according to two separate exit polls. The glaring irony is that senior citizens are also the most reliant on pensions, which face a worsening funding gap since the Brexit vote.

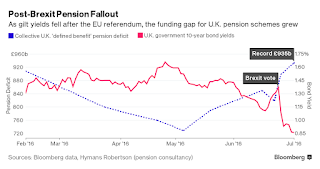

The combined deficits of all U.K. defined-benefit pension schemes, normally employer-sponsored and promising a specified monthly payment or benefit upon retirement, rose from 820 billion pounds ($1.1 trillion) to 900 billion pounds overnight following the referendum, according to pensions consultancy Hymans Robertson. Since then, it has grown further to a record 935 billion pounds as of July 1.

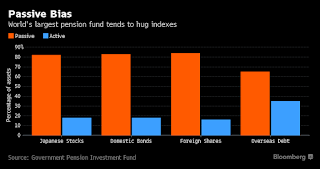

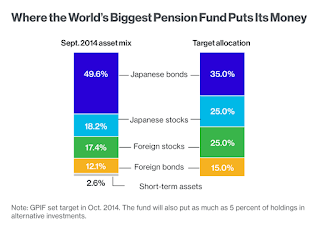

A sharp drop in U.K. government bond yields to record lows, and a similar decline in corporate bond yields, is largely to blame for the uptick in defined-benefit pension liabilities. That’s because fixed income represented 47.5 percent of total 2014 assets for corporate pensions funds, of which about three-quarters were issued by the U.K. government and/or sterling-denominated, according to the 2015 Investment Association Annual Survey.

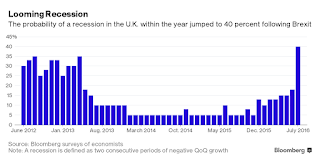

And the slump may not be over yet. While the Bank of England held off on cutting rates or increasing asset purchases at its July 14 meeting, early signals point to serious pain ahead for the U.K. economy. If additional quantitative easing is ultimately required to offset growing uncertainty, this would suggest “that bond yields are going to fall, which makes pensions a lot more expensive to provide,” former pensions minister Ros Altmann told Bloomberg. “Deficits would be larger if gilt yields fall further.”

Beyond gilt yields, Altmann said that anything that damages the economy is also bad news for pensions. The country’s gross domestic product is now expected to grow by 1.5 percent this year and just 0.6 percent in 2017, according to a Bloomberg survey of economists conducted July 15-20. That’s down from 1.8 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively, before the Brexit vote.

A weaker economy means companies will be less able to afford extra contributions precisely when pension schemes face a growing funding gap, possibly threatening future payouts to pensioners and creating a vicious feedback cycle. “If companies have got to put even more into their pension schemes than they have previously while their business is weakening, then clearly their business will be further weakened,” Altmann said.

Bad news, in other words, for Brexit’s biggest supporters.

Very bad news indeed but I guess British seniors weren’t thinking with their wallets as I thought they would when they decided to vote for Brexit.

Zlata Rodionova of the Independent also reports, Brexit supporters hit with record £935bn pension deficit because of the EU referendum:

The UK pension deficit hit a record level of £935 billion following UK’s vote to leave the EU, likely hitting pro-Brexit voters the hardest.

Support for the UK to leave the EU bloc grew with each age category, peaking at 60 per cent among those aged 65 and over, according to a survey of 12,356 referendum voters by Lord Ashcroft.

Ironically, the same voters are reliant on defined benefit pension to deliver their retirement income.

But UK’s pension deficit rose from £830 billion to £900 billion overnight following the EU referendum.

The vote then pushed the gap further to £935 billion as of July 1, according to Hymans Robertson, an independent pension’s consultancy, making it responsible for £115 billion of debt.

Gilt yields, the assets used to help value the cost of future payments, tumbled in the aftermath of the June 23 referendum, as investors bolted in favour of assets with a reputation for safety, putting more pressure on the pension industry.

Record lows in gilt yields in turn pushed the liabilities of UK pension schemes up to an all-time high £2.3 trillion on July 1.

“The gyrations in UK pension deficits are eye-watering. But one of the biggest factors that will determine whether or not pensions are paid to scheme members in full will be the health of the sponsoring company post Brexit,” Patrick Bloomfield, partner at Hymans Robertson, said.

Ros Altman, the former pensions minister, warned pensions could be under threat from the economic turmoil following UK’s vote to leave the EU.

“Good pensions depend on a good economy. Markets don’t like uncertainty, and we are clearly in unchartered territory,” Altmann said at an event in London.

“I hope we will get the political turmoil settled soon and do what we really need to be doing -which is making good policy for everyone in the country – who hopefully one day will be a pensioner if they aren’t one already,” she added.

As British businesses struggle to plan for an uncertain future in the aftermath of Britain’s decision to leave the EU, a worsening funding gap can reduce their scope to borrow money, curb their ability to invest and act as barrier to mergers and acquisitions.

High profile companies Tata Steel and BHS already showed evidence of the impact of pension deficits on investments and deal making this year.

The British Steel pension scheme, backed by Tata, has an estimated deficit of £700 million which has complicated the quest to find a new owner for Tata’s factories.

BHS’s pensions scheme had a £571 million hole when it collapsed. The risk of taking on the pensions burden is thought to be one of the reasons behind BHS’s failure to find backers or buyers for the business as a whole.

The fallout from Brexit on UK pensions is even more widespread than these articles suggest. Rob Langston of Raconteur reports, Brexit shock wave hits pension investors:

The full impact of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union has still to be felt, but uncertainty continues to affect pension investments as challenging times may lie ahead.

Pensions may not have been at the front of many people’s minds when entering the polling booths on June 23, but the Brexit referendum result is likely to have a lasting impact on pension schemes for years to come.

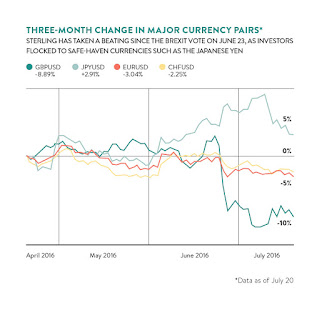

The immediate aftermath saw sterling plunge and markets fall, taking a toll on investors’ savings. But the longer-term effect may be just as significant.

While the impact of the EU referendum on markets may have trustees and pension scheme members seeking out the latest performance of their investments, there have been implications for the pension industry as a whole.

Ongoing annuity rates

For some scheme members close to retirement, the referendum result has had a major impact on their choices as annuity rates fell sharply post-Brexit.

“The cost of buying an annuity has got more expensive for DC [defined contribution] members close to retirement,” says Joanna Sharples, investment principal at consultancy Aon Hewitt. “Post-Brexit it will be really interesting to see how this translates across different annuity providers; however, quotes from one provider suggest that annuities are about 4 per cent more expensive, which is quite meaningful.”

Yet, the introduction of pension freedoms in April 2015 may have offered members a wider range of choices to mitigate the referendum result. Data from insurer and long-term investments industry body ABI suggests that annuity-buying activity has fallen away since the introduction of pension freedoms, with income drawdown products enjoying a corresponding rise in take-up.

Pension freedoms are likely to have a bearing on the type of investment decisions that are made in the post-referendum period, opening up opportunities to members they may not have enjoyed in previous years.

“Pensions freedoms have put existing default life cycles into question and there has been a sizeable shift from annuities to drawdown,” says Maya Bhandari, fund manager and director of the multi-asset allocation team at global asset manager Threadneedle Investments.

“We are now able to start on a blank sheet of paper and ask two crucial questions: what do people want and what do they need? Ultimately what people need is relatively simple tools and solutions that help them identify, manage or mitigate the three risks they face in retirement – financial market volatility, real returns and longevity.”

Brexit-proofing pensions

In light of the uncertainty brought about by Brexit, more scheme members might choose to take greater control over their pension savings. So-called Brexit-proofing pensions may appeal to many investors, although they will face a number of challenges.

“Pensions freedoms are still relatively new, which means people are currently faced with very mixed messages about how best to act in times of market uncertainty,” says Catherine McKenna, global head of pensions at law firm Squire Patton Boggs.

“We already know that one of the biggest trends of 2015 was the rise of the pensions scam and individuals should be careful to guard against Brexit uncertainty being used as a trigger to cash out their fund if this isn’t right for them.”

While the referendum decision and subsequent government shake-up may have ramifications for pension freedoms, any changes to existing pension legislation are unlikely to emerge in the immediate aftermath of the leave vote.

“In terms of legislation on pension freedoms, it is unlikely that the government will look to repeal what is already in place but, irrespective of Brexit, there may be further regulation to impose better value by reducing charges and product design for freedoms to develop,” says Ms McKenna.

Taking greater control of investment decisions in the current environment may pose a number of challenges, however, particularly with the increased level of volatility in markets seen in the wake of the result.

“From an investment perspective, Brexit has created much greater uncertainty and volatility in the markets, and made them more than usually reactive to political events,” says James Redgrave, European retirement director at asset management research and consultancy provider Strategic Insight.

“The FTSE 100 fell 500 points on June 24 – below 6,000 – and savers entitled to access their pots were advised to wait to take cash, if they could afford to do so.

“These markets have settled largely on the quick and orderly transition to a new government, after David Cameron’s resignation, and will have been buoyed by the Bank of England’s conclusion that an interest rate cut is not economically necessary.”

James Horniman, portfolio manager at investment manager James Hambro & Partners, says: “Investors have to position portfolios sensibly with insurance against all outcomes. Sterling is likely to come under continued pressure and there will almost certainly be volatility.

“As long as valuations are not unreasonable, it makes sense to weight any UK equity holdings towards businesses with strong US-dollar earnings rather than those reliant on raw materials from overseas – companies forced by adverse currency movements to pay extra for essential inputs from elsewhere in the world could see their profits really squeezed.”

The impact of home bias is likely to take a toll on some pension investments as fund managers have warned of being too exposed to the UK market. Under normal circumstances higher UK equities exposure may be expected, but the uncertainty introduced by the referendum result in local markets may harm returns.

Long term plans

Experts note that many trustees have already begun diversifying portfolios to mitigate geography and asset risk. The financial crisis remains a fresh memory for many trustees who will have taken a more robust approach to diversification in recent years.

“There’s been a general trend over the past decade of moving away from fund manager mandates that are very specific and narrow to wider mandates, such as global equities or multi-asset,” says Dan Mikulskis, head of defined benefit (DB) pensions at London-based investment consultancy Redington. “Trustees making fund manager changes will be more motivated to move to less constrained mandates.”

Yet, trustees and scheme members may need to get used to new market conditions and a longer-term, low-growth environment.

“Following Brexit, the conversations we’ve been having with investors are similar to those we’ve been having since the start of the year,” says Ana Harris, head of equity portfolio strategists for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at investment manager State Street Global Advisors.

“We haven’t seen a big shift in money or allocations, but there has been some realignment. What we are advising clients is not to be reactive to short-term volatility in the market and make sure plans for long-term investment are in place.”

“In the short term, it is likely there will be quite a lot of volatility in the market and members need to be aware of that,” says Aon Hewitt’s Ms Sharples. “One option is that everybody carries on as before with no change to strategy; however, the other option is trustees think about whether there are better ways of investing and opportunities to provide more diversification or add value.

“For people who are a bit further away from retirement, the key is what kind of returns can they expect going forward? Returns are likely to be lower than before because of pressure on the economy and lower growth expectations. To help offset this, members have the option of paying more in or retiring later, or a combination of both.”

With further details yet to emerge about what access the UK will have to EU markets and restrictions on free movement, the full impact of Brexit remains to be seen.

“Unfortunately, no one has a crystal ball. Even the best investment strategies may be adversely affected by current market volatility, but this is not to say members, trustees or fund managers should begin to panic,” says Ms McKenna of Squire Patton Boggs.

“There is little doubt that Britain leaving the EU will mean there are challenges ahead for investment funds; however, there are also opportunities for trustees to harness innovation and consider new investment portfolios.”

A greater focus on risk management has emerged as trustees attempt to mitigate some of the impact of June’s EU referendum result on pension schemes.

While attention may be focused on markets, pension scheme trustees will also have to consider a number of other risk management issues brought about by Brexit.

“I don’t think pensions should be focusing too much on whether sterling is going up or down, or whether one asset manager is performing,” says Dan Mikulskis, head of defined benefit pensions at investment consultancy Redington.

“Getting a risk management framework set up is sensible. With a simple framework to go by, there will be opportunities in a volatile market environment, but it’s always best left to the asset manager.”

Mr Mikulskis says regular reviewing of investment decisions and performance is likely to depend on the size of the scheme and the governance arrangements, adding that trustees may be put under pressure to communicate more frequently and effectively with scheme members.

Despite low interest rates, trustees should take care over possible liability hedging, while also recognising the challenges presented by a low-yield environment for bonds.

“We don’t think that just because rates are low they can’t fall further,” he says. “A lot of trustees that haven’t hedged will feel like they’ve missed the boat, but there are still risks on the down side.”

There sure are risks to the downside and trustees ignoring the bond market’s ominous warning are going to regret not hedging their liabilities because if you ask me, ultra low rates and the new negative normal are here to stay, especially if the deflation tsunami I’ve warned of hits us.

Brexit isn’t just hitting UK pensions, it’s also going to hit large Canadian pensions which invested billions in UK infrastructure and commercial real estate. They were right to worry about Brexit and if they didn’t hedge their currency risk, they will suffer material losses in the short-term.

However, Canada’s large pensions have a very long investment horizon, so over the long run these losses can become big gains especially if Britain figures out a way to continue trading with the EU after Brexit.

That all remains to be seen. In my opinion, Brexit was Europe’s Minsky moment and if they don’t wake up and fix serious structural deficiencies plaguing the EU, then the future looks bleak for this fragile union.

Brexit’s shock waves are also being felt in Japan where the yen keeps soaring, placing pressure on the Bank of Japan which is also grappling with expansionary fiscal policy. We’ll see what it decides on Friday but investors are bracing for another letdown.

In other related news, while Brexit’s biggest fans are in big trouble, Chris Havergal of the Times Higher Education reports, Bonuses up at USS as pension fund deficit grows by £1.8 billion:

Bonuses at the university sector’s main pension fund have soared, even though its deficit has grown by £1.8 billion.

The annual report of the Universities Superannuation Scheme says that the shortfall between its assets and the value of pensions due to members was estimated to be £10 billion at the end of March, compared with £8.2 billion last year and predating any negative effect of the Brexit vote on pensions schemes.

The health of the fund is due to be reassessed in 2017 and Bill Galvin, its chief executive, said that it was “too early” to say whether contributions from employers and employees would need to be increased.

Despite the expanding deficit, the annual report reveals that the value of bonuses paid to staff rocketed from £10.1 million to £18.2 million last year, with the vast bulk going to the scheme’s investment team.

This contributed to the number of USS employees earning more than £200,000 once salary and bonuses are combined increasing from 29 to 51 year-on-year.

Thirteen staff earned more than £500,000, up from three the year before. While the highest-paid employee in 2014-15 received between £900,000 and £950,000, last year one worker earned about £1.6 million, with another on about £1.4 million.

Mr Galvin told Times Higher Education that the increases reflected a decision to take investment activities in-house that were previously outsourced, and strong investment performance that meant that the deficit was £2.2 billion smaller than it would otherwise have been.

“Although bonuses to the investment teams have gone up, it reflects the fact they have contributed very substantially to keep the deficit from being in a worse position than it is,” Mr Galvin said. “We are delivering a very good value pension scheme, better than any other comparable schemes we have benchmarked.”

The report shows that Mr Galvin’s total remuneration, including pension contributions, increased by 12 per cent in 2015-16, from £432,000 to £484,000.

This comes after a summer of strike action by academics – many of whom will be USS members, particularly at pre-92 universities – over an offer of a 1.1 per cent pay rise for 2016-17.

The increased deficit means that the scheme’s pensions are now estimated to be only 83 per cent funded, compared with the 90 per cent figure predicted by the last revaluation in 2014.

Mr Galvin said that the assumptions made two years ago had been “reasonable”, but that asset values had not kept pace with declining interest rates.

The last revaluation led to the closure of the USS’ final salary pension scheme and an increase in contributions by employers and employees, but Mr Galvin said that a long-term assessment would be taken to determine if further changes were needed.

“Some of the things that will be relevant in the 2017 valuation have gone against [us] in terms of the assumptions we made at the last valuation,” Mr Galvin said. “That is a signal and we will consider what we should do about that…[but] it’s too early to say whether we do need to make any response or what that response might be.”

Mr Galvin added that, while an increase in liabilities since Brexit had been “broadly balanced” with an increase in the value of assets, it was “much too early” to determine the longer term impact of the UK leaving the European Union on the fund.

Looks like the Canadian pension compensation model has been adopted in the United Kingdom. That reminds me, I need to update the list of highest paid pension officers, but keep in mind Mr. Gavin is right, taking investment activities in-house saves the scheme money and it requires they pay competitive compensation to their senior investment officers.

Lastly, Elizabeth Pain of Science Magazine reports, Pan-European pension fund for scientists leaves the station:

Old age may not be something European scientists think about as they hop around the continent in search of exciting Ph.D. opportunities, broader postdoctoral experience, or attractive faculty positions. But once they approach retirement age, many realize that working in countries as diverse as Estonia, Spain, or Germany can be detrimental to one’s nest egg.

But now, there is a potential solution: a pan-European pension fund for researchers, called RESAVER, that was set up by a consortium of employers to stimulate researcher mobility. The fund was officially created on 14 July under Belgian law as a Brussels-based organization. Three founding members—the Central European University in Budapest; Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste in Basovizza, Italy; and the Central European Research Infrastructure Consortium headquartered in Trieste, Italy—will soon start making their first contributions. Researchers can also contribute part of their own salary to the fund.

“We have a solution” to preserve the pension benefits of mobile researchers, Paul Jankowitsch, who is the former chair of the RESAVER consortium and now oversees membership and promotion, said earlier this week here at the EuroScience Open Forum (ESOF). “The excuse [for institutions] to do nothing is gone.”

The European Commission has contributed €4 million to the set-up costs of RESAVER, as part of its funding program Horizon 2020. At least in principle, the fund is open to the entire European Economic Area, which includes all 28 E.U. member states except Croatia, as well as Norway, Lichtenstein, and Iceland.

Most European countries offer social security, and it’s usually possible to get access to benefits even if they’re accumulated in another country. But many universities and institutions also provide supplemental pension benefits that are not so easily transferred. Researchers who spend part of their career abroad—even if it’s just a few hundred kilometers from home—can find themselves paying into a variety of supplemental plans, often resulting in lower benefits than they would enjoy if they just stayed put. This puts a damper on scientists’ mobility.

The idea behind RESAVER is to create a common pension fund so that supplemental benefits will simply follow scientists whenever they change jobs or countries. Individual researchers can only join through their employers, which is why it’s essential for the scheme’s success that a large number of institutions around Europe join the initiative.

The big question is whether that will happen. In addition to the three early adopters, the RESAVER consortium, which was created in 2014, has some 20 members so far, together representing more than 200 institutions across Europe. That’s just a tiny fraction of Europe’s research landscape—and even most members of the consortium have not yet committed to joining the fund.

Take-up has been slow for a variety of reasons. According to Jankowitsch, the fund represents a long-term financial risk that many universities and research institutions are not accustomed to. Local factors further complicate matters. In France, many researchers have their pension fully covered by the state as civil servants. Although many institutions in Spain are part of the consortium, there are obstacles in Spanish law to joining a foreign pension fund. And in Germany, researchers at the Max Planck Institutes have little incentive to join because they already enjoy attractive pension packages.

Risk was also a concern for researchers in the audience at this week’s ESOF session. The RESAVER pension plan will be contribution- rather than benefit-based, meaning that researchers will know how much they put in but not how much they’ll get, as they would with many other pension plans in Europe. Although the fund has been conceived as a pan-European risk-pooling investment, Jankowitsch acknowledges that there will always be risks in the capital market.

Some attendees also wondered whether, with so few institutions participating, RESAVER could actually be a barrier to mobility, at least in the short term, by limiting researchers to those institutions. Young researchers worried about inequalities because Ph.D. candidates are employed in some places but are considered students in others, making them ineligible for participation. (The consortium is currently negotiating a private pension plan for researchers who don’t have an employment contract.)

The International Consortium of Research Staff Associations (ICoRSA) would like to see more transparency in the fund’s investment plan and more flexibility and guarantees for researchers, the organization says in a position statement sent to ScienceInsider today. But overall, “ICoRSA welcomes the initiative.”

Jankowitsch is optimistic: “We see a lot of questions, but not obstacles,” he said at ESOF. Institutes can benefit, because offering RESAVER to employees could give them a competitive hiring advantage, Jankowitsch said—but he encouraged researchers to urge their employers to join, if necessary. “If organizations are not joining, then this is not happening.”

This is an interesting idea but they should have modeled it after CERN’s pension plan which is a defined-benefit plan that thinks like a global macro fund. CERN’s former CIO, Theodore Economou is now CIO of Lombard Odier and he’s a great person to discuss this initiative with.

But before they launch RESAVER to bolster the pensions of European scientists, European policymakers and UK’s new leaders need to sit down and RESAVE the Euro.