Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

BusinessWire reports, World’s Largest Institutional Investors Expecting More Asset Allocation Changes over Next Two Years Than in the Past:

Institutional investors worldwide are expecting to make more asset allocation changes in the next one to two years than in 2012 and 2014, according to the new Fidelity Global Institutional Investor Survey. Now in its 14th year, the Fidelity Global Institutional Investor Survey is the world’s largest study of its kind examining the top-of-mind themes of institutional investors. Survey respondents included 933 institutions in 25 countries with $21 trillion in investable assets.

The anticipated shifts are most remarkable with alternative investments, domestic fixed income, and cash. Globally, 72 percent of institutional investors say they will increase their allocation of illiquid alternatives in 2017 and 2018, with significant numbers as well for domestic fixed income (64 percent), cash (55 percent), and liquid alternatives (42 percent).

However, institutional investors in some regions are bucking the trend seen in other parts of the world. Many institutional investors in the U.S. are, on a relative basis, adopting a wait-and-see approach. For example, compared to 2012, the percentage of U.S. institutional investors expecting to move away from domestic equity has fallen significantly from 51 to 28 percent, while the number of respondents who expect to increase their allocation to the same asset class has only risen from 8 to 11 percent.

“With 2017 just around the corner, the asset allocation outlook for global institutional investors appears to be driven largely by the local economic realities and political uncertainties in which they’re operating,” said Scott E. Couto, president, Fidelity Institutional Asset Management. “The U.S. is likely to see its first rate hike in 12 months, which helps to explain why many in the country are hitting the pause button when it comes to changing their asset allocation.

“Institutions are increasingly managing their portfolios in a more dynamic manner, which means they are making more investment decisions today than they have in the past. In addition, the expectations of lower return and higher market volatility are driving more institutions into less commonly used assets, such as illiquid investments,” continued Couto. “For these reasons, organizations may find value in reexamining their investment decision-making process as there may be opportunities to bring more structure and accommodate the increased number of decisions, freeing up time for other areas of portfolio management and governance.”

Primary concerns for institutional investors

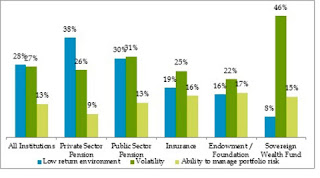

Overall, the top concerns for institutional investors are a low-return environment (28 percent) and market volatility (27 percent), with the survey showing that institutions are expressing more worry about capital markets than in previous years. In 2010, 25 percent of survey respondents cited a low-return environment as a concern and 22 percent cited market volatility.

“As the geopolitical and market environments evolve, institutional investors are increasingly expressing concern about how market returns and volatility will impact their portfolios,” said Derek Young, vice chairman of Fidelity Institutional Asset Management and president of Fidelity Global Asset Allocation. “Expectations that strengthening economies would build enough momentum to support higher interest rates and diminished volatility have not borne out, particularly in emerging Asia and Europe.”

Investment concerns also vary according to the institution type. Globally, sovereign wealth funds (46 percent), public sector pensions (31 percent), insurance companies (25 percent), and endowments and foundations (22 percent) are most worried about market volatility. However, a low-return environment is the top concern for private sector pensions (38 percent). (click on image)

Continued confidence among institutional investors

Despite their concerns, nearly all institutional investors surveyed (96 percent) believe that they can still generate alpha over their benchmarks to meet their growth objectives. The majority (56 percent) of survey respondents say growth, including capital and funded status growth, remain their primary investment objective, similar to 52 percent in 2014.

On average, institutional investors are targeting to achieve approximately a 6 percent required return. On top of that, they are confident of generating 2 percent alpha every year, with roughly half of their excess return over the next three years coming from shorter-term decisions such as individual manager outperformance and tactical asset allocation.

“Despite uncertainty in a number of markets around the world, institutional investors remain confident in their ability to generate investment returns, with a majority believing they enjoy a competitive advantage because of confidence in their staff or access to better managers,” added Young. “More importantly, these institutional investors understand that taking on more risk, including moving away from public markets, is just one of many ways that can help them achieve their return objectives. In taking this approach, we expect many institutions will benefit in evaluating not only what investments are made, but also how the investment decisions are implemented.”

Improving the Investment Decision-Making Process

There are a number of similarities in institutional investors’ decision-making process:

- Nearly half (46 percent) of institutional investors in Europe and Asia have changed their investment approach in the last three years, although that number is smaller in the Americas (11 percent). Across the global institutional investors surveyed, the most common change was to add more inputs – both quantitative and qualitative – to the decision-making process.

- A large number of institutional investors have to grapple with behavioral biases when helping their institutions make investment decisions. Around the world, institutional investors report that they consider a number of qualitative factors when they make investment recommendations. At least 85 percent of survey respondents say board member emotions (90 percent), board dynamics (94 percent), and press coverage (86 percent) have at least some impact on asset allocation decisions, with around one-third reporting that these factors have a significant impact.

“Institutional investors often assess quantitative factors such as performance when making investment recommendations, while also managing external dynamics such as the board, peers and industry news as their institutions move toward their decisions. Whether it’s qualitative or quantitative factors, institutional investors today face an information overload,” said Couto. “To keep up with the overwhelming amount of data, institutional investors should consider revisiting and evolving their investment process.

“A more disciplined investment process may help them achieve more efficient, effective and repeatable portfolio outcomes, particularly in a low-return environment characterized by more expected asset allocation changes and a greater global interest in alternative asset classes,” added Couto.

The complete report with a wealth of charts is available on request. For additional materials on the survey, go to institutional.fidelity.com/globalsurvey.

About the Survey

Fidelity Institutional Asset ManagementSM conducted the Fidelity Global Institutional Investor Survey of institutional investors in the summer of 2016, including 933 investors in 25 countries (174 U.S. corporate pension plans, 77 U.S. government pension plans, 51 non-profits and other U.S. institutions, 101 Canadian, 20 other North American, 350 European, 150 Asian, and 10 African institutions including pensions, insurance companies and financial institutions). Assets under management represented by respondents totaled more than USD $21 trillion. The surveys were executed in association with Strategic Insight, Inc. in North America and the Financial Times in all other regions. CEOs, COOs, CFOs, and CIOs responded to an online questionnaire or telephone inquiry.

About Fidelity Institutional Asset Management℠

Fidelity Institutional Asset Management℠ (FIAM) is one of the largest organizations serving the U.S. institutional marketplace. It works with financial advisors and advisory firms, offering them resources to help investors plan and achieve their goals; it also works with institutions and consultants to meet their varying and custom investment needs. Fidelity Institutional Asset Management℠ provides actionable strategies, enabling its clients to stand out in the marketplace, and is a gateway to Fidelity’s original insight and diverse investment capabilities across equity, fixed income, high‐income and global asset allocation. Fidelity Institutional Asset Management is a division of Fidelity Investments.

About Fidelity Investments

Fidelity’s mission is to inspire better futures and deliver better outcomes for the customers and businesses we serve. With assets under administration of $5.5 trillion, including managed assets of $2.1 trillion as of October 31, 2016, we focus on meeting the unique needs of a diverse set of customers: helping more than 25 million people invest their own life savings, nearly 20,000 businesses manage employee benefit programs, as well as providing nearly 10,000 advisory firms with investment and technology solutions to invest their own clients’ money. Privately held for 70 years, Fidelity employs 45,000 associates who are focused on the long-term success of our customers. For more information about Fidelity Investments, visit https://www.fidelity.com/about.

Sam Forgione of Reuters also reports, Institutions aim to boost bets on hedge funds, private equity:

The majority of institutional investors worldwide are seeking to increase their investments in riskier alternatives that are not publicly traded such as hedge funds, real estate and private equity over the next one to two years to combat potential low returns and choppiness in public markets, a Fidelity survey showed on Thursday.

The Fidelity Global Institutional Investor Survey showed that 72 percent of institutional investors worldwide, from public pension funds to insurance companies and endowments, said they would increase their exposure to these so-called illiquid alternatives in 2017 and 2018.

The survey, which included 933 institutions in 25 countries overseeing a total of $21 trillion in assets, found that the institutions were most concerned with a low-return investing environment over the next one to two years, with 28 percent of respondents citing it as such. Market volatility was the second-biggest worry, with 27 percent of respondents citing it as their top concern.

Private sector pensions were most concerned about a low-return environment, with 38 percent of them identifying it as their top worry, while sovereign wealth funds were most nervous about volatility, with 46 percent identifying it as their top concern.

“With the concern about the low-return environment as well as market volatility, as a result we’re seeing more of an interest in alternatives, where there’s a perception of higher return opportunities,” said Derek Young, vice chairman of Fidelity Institutional Asset Management and president of Fidelity Global Asset Allocation.

Investors seek alternatives, which may invest in assets such as timber or real estate or use tactics such as betting against securities, for “uncorrelated” returns that do not move in tandem with traditional stock and bond markets.

Young noted, however, that illiquid alternatives can also be volatile without it being obvious, since they lack daily pricing and as a result may give the perception of being less volatile.

“We would hope and would expect that institutional investors would appreciate the volatility that still exists within the underlying investments,” he said in reference to illiquid alternatives.

The survey, which was conducted over the summer, found that despite their concerns, 96 percent of the institutions believed they could achieve an 8 percent investment return on average in coming years.

U.S. public pension plans, on average, had about 12.1 percent of their assets in real estate, private equity and hedge funds combined as of Sept. 30, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service data.

And Jonathan Ratner of the National Post reports, Low returns, high volatility top institutional investors’ list of concerns:

Low returns and market volatility topped the list of concerns in Fidelity Investments’ annual survey of more than 900 institutional investors with US$21 trillion of investable assets.

Thirty per cent of respondents cited the low-return environment as their primary worry, followed by volatility at 27 per cent.

“Expectations that strengthening economies would build enough momentum to support higher interest rates and diminished volatility have not borne out, particularly in emerging Asia and Europe,” said Derek Young, vice chairman of Fidelity Institutional Asset Management and president of Fidelity Global Asset Allocation.

The Fidelity Global Institutional Survey, which is now in its 14th year and includes investors in 25 countries, also showed that institutions are growing more concerned about capital markets.

Despite these issues, 96 per cent of institutional investors surveyed believe they can beat their benchmarks.

The group is targeting an average return of approximately six per cent per year, in addition to two per cent alpha, and short-term decisions are being credited for those excess returns.

Institutional investors remain confident in their return prospects due to their access to superior money managers. They also have demonstrated a willingness to move away from public markets.

On a global basis, 72 per cent of institutional investors said they plan to increase their exposure to illiquid alternatives in 2017 and 2018.

Domestic fixed income (64 per cent), cash (55 per cent) and liquid alternatives (42 per cent) were the other areas where increased allocation is expected to occur.

However, institutional investors in the U.S. are bucking this trend, and seem to have adopted a “wait-and-see” approach.

The percentage of this group expecting to move away from domestic equity has fallen from 51 per cent in 2012, to 28 per cent this year. Meanwhile, the number of respondents who plan to increase their allocation to U.S. equities has risen to just 11 per cent from eight per cent in 2012.

“With 2017 just around the corner, the asset allocation outlook for global institutional investors appears to be driven largely by the local economic realities and political uncertainties in which they’re operating,” said Scott Couto, president of Fidelity Institutional Asset Management.

He noted that with the Federal Reserve expected to produce its first rate hike in 12 months, it’s understandable why many U.S. investors are hitting the pause button when it comes to asset allocation changes.

On Thursday, I had a chance to speak to Derek Young, vice chairman of Fidelity Institutional Asset Management and president of Fidelity Global Asset Allocation. I want to first thank him for taking the time to go over this survey with me and thank Nicole Goodnow for contacting me to arrange this discussion.

I can’t say I am shocked by the results of the survey. Since Fidelity did the last one two years ago, global interest rates plummeted to record lows, public markets have been a lot more volatile and return expectations have diminished considerably.

One thing that did surprise me from this survey is that the majority of institutions (96%) are confident they can beat their benchmark, “targeting an average return of approximately six per cent per year, in addition to two per cent alpha, and short-term decisions are being credited for those excess returns.”

I personally think this is wishful thinking on their part, especially if they start piling into illiquid alternatives at the worst possible time (see my write-up on Bob Princes’ visit to Montreal).

In our discussion, however, Derek Young told me institutions are confident that through strategic and tactical asset allocation decisions they can beat their benchmark and achieve that 8% bogey over the long run.

He mentioned that tactical asset allocation will require good governance and good manager selection. We both agreed that the performance dispersion between top and bottom quartile hedge funds is huge and that manager selection risk is high for liquid and illiquid alternatives.

Funding illiquid alternatives is increasingly coming from equity portfolios, except in the US where they have been piling into alternatives for such a long time that they probably want to pause and reflect on the success of these programs, especially considering the fees they are paying to external managers.

The move into bonds was interesting. Derek told me as rates go up, liabilities fall and if rates are going up because the economy is improving, this is also supportive of higher equity prices. He added that many institutions are waiting for the “right funding status” so they can derisk their plans and start immunizing their portfolios.

In my comment on trumping the bond market, I suggested taking advantage of the recent backup in yields to load up on US long bonds (TLT). I still maintain this recommendation and think anyone shorting bonds at these levels is out of their mind (click on chart):

Sure, rates can go higher and bond prices lower but these big selloffs in US long bonds are a huge buying opportunity and any institution waiting for the yield on the 10-year Treasury note to hit 3%+ to begin derisking and immunizing their portfolio might end up regretting it later on.

Our discussion on the specific concerns of various institutions was equally interesting. Derek told me many sovereign wealth funds need liquidity to fund projects. They are the “funding source for their economies” which is why volatile returns are their chief concern. (Oftentimes, they will go to Fidelity to redeem some money and tell them “we will come back to you later”).

So unlike pensions, SWFs don’t have a liability concern but they are concerned about volatile markets and being forced to sell assets at the wrong time (this surprised me).

Insurance companies are more concerned about hedging volatility risk to cover their annuity contracts. In 2008, when volatility surged, they found it extremely expensive to hedge these risks. Fidelity manages a volatility portfolio for their insurance clients to manage this risk on a cost effective basis.

I told Derek that they should do the same thing for pension plans, managing contribution volatility risk for plan sponsors. He told me Fidelity is already doing this for smaller plans (outsourced CIO) and for larger plans they are helping them with tactical asset allocation decisions, manager selection and other strategies to achieve their targets.

On the international differences, he told me UK investors are looking to allocate more to illiquid alternatives, something which I touched upon in my last comment on the UK’s pension crisis.

As far as Canadian pensions, he told me “they are very sophisticated” which is why I told him many of them are going direct when it comes to alternative investments and more liquid absolute return strategies.

In terms of illiquid alternatives, we both agreed illiquidity doesn’t mean there are less risks. That is a total fallacy. I told him there are four key reasons why Canada’s large pensions are increasing their allocations to private market investments:

- They have a very long investment horizon and can afford to take on illiquidity risk.

- They believe there are inefficiencies in private markets and that is where the bulk of alpha lies.

- They can scale into big real estate and infrastructure investments a lot easier than scaling into many hedge funds or even private equity funds.

- Stale pricing (assets are valued with a lag) means that private markets do not move in unison with public markets, so it helps boost their compensation which is based on four-year rolling returns (privates dampen volatility of overall returns during bear markets).

Sure, private markets are good for beneficiaries of the plan, especially if done properly, but they are also good for the executive compensation of senior Canadian pension fund managers. They aren’t making the compensation of elite hedge fund portfolio managers but they’re not too far off.

On that note, I thank Fidelity’s Derek Young and Nicole Goodnow and remind all of you to please subscribe and donate to this blog (pensionpulse.blogspot.ca) on the top right-hand side under my picture and show your appreciation of the work that goes into these blog comments.

I typically reserve Fridays for my market comments but there were so many things going on this week (OPEC, jobs report, etc.) that I need to go over my charts and research over the weekend.

One thing I can tell you is that US long bonds remain a big buy for me and I was watching the trading action on energy, metal and mining stocks all week and think a lot of irrational exuberance is going on there. There are great opportunities in this market on the long and short side, but will need to gather my thoughts and discuss this next week.