Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

John W. Schoen of CNBC reports, States face pension fund gap approaching $1 trillion:

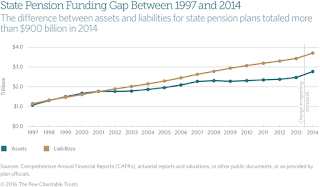

After years of not setting aside enough money, state pension funds are looking at a $1 trillion shortfall in what they owe workers in benefits, according to to a new analysis from The Pew Charitable Trusts.

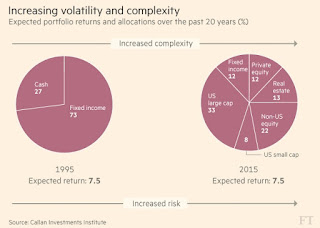

State retirement systems caught a break with strong investment returns in fiscal 2014, but the gap is expected to top $1 trillion in fiscal 2015, the last fiscal year with full results (click on image).

“The lesson here is that state and local policymakers cannot count solely on investment returns to close the pension funding gap over the long term,” the report said.

While many states have cut benefits for new workers and frozen plans for current staff, they cannot cut benefits that have already been earned by public employees. That means they have to find money to make up the shortfall by cutting other programs, raising taxes or both.

The report is based on the most recent data from all 50 states, which are typically reported as much as a year after each fiscal year ends.

States were to make up $35 billion of their unfunded liabilities in fiscal 2014, leaving a shortfall of $934 billion. That’s because of unusually strong returns averaging 17 percent in 2014, according to the study. But average returns fell sharply in 2015, it said, to just 3 percent.

The numbers for fiscal 2016, which ended on June 30 for most states, won’t be reported for some time. But investment gains are expected to work against them. Pew reports that public pension funds had negative average returns during the first three quarters of the latest fiscal year.

Those lower returns mean states with badly underfunded retirement plans will have to set aside more tax dollars to fill the shortfall.

States with the biggest funding gaps include Illinois and Kentucky, the two worst-funded systems, with just 41 percent of what’s needed to pay the benefits promised to public employees. New Jersey has set aside just 42 percent (click on image):

Only three states have set aside enough money to fully pay retirement benefits owed to current and futures retirees: South Dakota (107 percent of liabilities), Oregon (104 percent) and Wisconsin (103 percent).

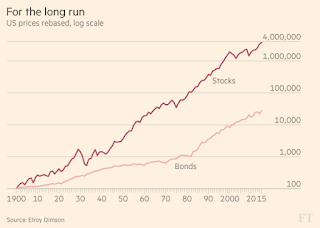

State pension fund debts have been growing since 2000, after falling in the preceding decades. The last time they were fully funded was the late 1990s, when a stock market boom generated returns that left them with a surplus of funds to pay benefits (click on image).

Let’s have a closer look at The Pew Charitable Trusts’s analysis on state pension deficits, The State Pension Funding Gap: 2014:

The nation’s state-run retirement systems had a $934 billion gap in fiscal year 2014 between the pension benefits that governments have promised their workers and the funding available to meet those obligations. That represents a $35 billion decrease from the shortfall reported for fiscal 2013. The reduction in pension debt was driven primarily by strong investment results, with public plans in fiscal 2014 averaging a 17 percent rate of return.

This brief focuses on the most recent comprehensive data from all 50 states and does not reflect the impact of weaker investment performance in fiscal 2015, which averaged 3 percent. Performance has been even weaker in the first three quarters of fiscal 2016, with negative average returns. Preliminary data from fiscal 2015 point to increases in unfunded liabilities for the majority of states. Total pension debt is expected to be over $1 trillion for state plans, an increase of more than 10 percent from fiscal 2014.

When combined with the shortfalls in local pension systems, this estimate reaches more than $1.5 trillion for fiscal 2015 and will likely remain close to historically high levels as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). The lesson here is that state and local policymakers cannot count solely on investment returns to close the pension funding gap over the long term; they also need to follow funding policies that put them on track to pay down pension debt.

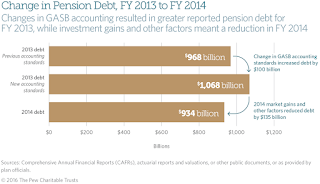

These data follow new standards from the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), the independent organization recognized by governments, the accounting industry, and capital markets as the official source of generally accepted accounting principles for state and local governments. As of June 15, 2014, GASB required governments to report pension debt as a net pension liability (NPL) on their annual balance sheets and to disclose more details on the cost of new pension benefits earned by current workers. In addition, some poorly funded plans must now use more conservative assumptions when calculating pension liabilities for reporting purposes.

Under the new rules, reporting on pensions is more closely tied to general accounting standards, rather than to plans’ individual funding policies. In particular, plans are no longer required to report the actuarial required contribution, known as the ARC, which had been the most common metric for assessing contribution adequacy. Although most plans have continued to include the ARC as a supplemental disclosure—or produced a similar metric known under the new GASB standards as the actuarially determined contribution (ADC)—these measures are based on each plan’s own assumptions and do not always signal true fiscal health. The Pew Charitable Trusts did not include those calculations in this brief because the ARC is not consistently available and the ADC does not have to meet minimum standards. Neither metric on its own provides sufficient information to evaluate the policies that states are following to fund their pension promises.

The analysis also looks at net amortization, a new 50-state metric that can help state and local governments understand whether their funding policies are adequate to reduce pension debt. Net amortization serves as a benchmark to assess contribution policies and helps gauge whether payments to a pension plan are sufficient, both to pay for the cost of new benefits and to make progress on shrinking unfunded liabilities. The calculation is based on the assumptions that plans use to determine liability and estimate long-term investment returns; it also accounts for employee contributions, given that workers in most states contribute to pensions.

………………

What Is Net Amortization?

Net amortization measures whether total contributions to a public retirement system would have been sufficient to reduce unfunded liabilities if all expectations had been met for that year. The calculation uses the plan’s own reported numbers as well as assumptions about investment returns. Plans that consistently fall short of this benchmark can expect to see the gap between the liability for promised benefits and available funds grow over time.

………………

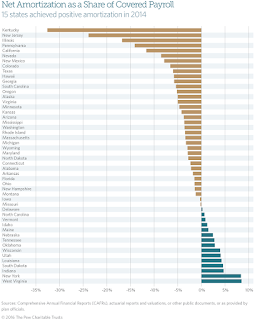

Under this new metric, states that follow contribution policies that are sufficient to pay down pension debt if plan assumptions are met are achieving positive amortization. States where contributions allow the funding gap to continue to grow are facing negative amortization. The analysis in this brief shows that 15 states currently follow policies that meet the positive amortization benchmark—exceeding 100 percent of needed funding—and can be expected to reduce pension debt in the near term. The remaining 35 states fell short; those performing the worst on this measure typically had the largest unfunded pension liabilities.

While 40 states reported decreased unfunded liabilities in 2014, only a small number met the positive amortization benchmark because the calculation is based on the long-term assumptions that plans use to set funding policy, including expectations for the rate of return on investments. In the short term, states experienced stronger-than-expected investment returns, which helped reduce reported pension debt. However, investment returns vary widely over time, and most governments that sponsor pension plans made contributions that were not large enough to reduce debt based on expected long-term rates of return.

New accounting standards spotlight poorly funded plans

The new disclosure rules require that state balance sheets now include the net pension liability, which is the difference between pension plan assets, reported as plan net position, and total pension liability. Net pension liability is essentially the pension debt, or unfunded liability, for that plan. All plans now calculate assets based on the market value of investments on the reporting date, rather than smoothing investment gains and losses over time, which had previously been allowed. This means that the 2014 results fully reflect the impact of strong market gains. Going forward, reported asset values will be more volatile from year to year. For example, funded levels are projected to decline for fiscal 2015 because the average returns of 3 percent were well below plans’ long-term return targets.

In addition, the new standards now require certain plans with low funded ratios to report pension liabilities using more conservative investment return assumptions. (See Appendix B for a more detailed explanation.) So far, this new requirement has had an impact on only eight of the 100 largest state-sponsored pension plans. Looking at restated 2013 results, this accounts for about $72 billion in increased reported pension liabilities and pension debt in total. Plans in Illinois and New Jersey, along with the Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System and the Texas Employees Retirement System, account for over 90 percent of this amount.

The new rules also require that all public pension plans use the same methodology to calculate liabilities. Previously, state pension plans could choose from multiple approaches, though most had been using the approach that is now required.

Primarily because of market gains, the state pension funding gap dropped in 2014, the first decline in reported pension debt since 2000. Lower investment returns in 2015, however, indicate that pension debt will increase when valuations for that year are complete.

The volatility in investment returns between 2014 and 2015 demonstrates that states cannot rely on higher-than-expected returns to eliminate unfunded liabilities. Pew’s net amortization analysis provides a benchmark for measuring the sufficiency of contributions based on long-term investment return assumptions. This analysis shows that states in aggregate fell short of the net amortization benchmark by $29 billion in 2014.

Figure 2 shows the impact that changes in accounting standards had on total reported pension debt in 2013 as well as the effects of investment gains and other factors in 2014.

Figure 2 (click on image)

While these new standards are required for all plans, most continue to report information using the previous standards as well. The prior rules allowed plans to report assets smoothed over multiple years and did not require the use of more conservative assumptions to report liabilities, as described above. In this analysis and going forward, Pew will use data reported under the most recent set of GASB standards because they provide a standardized point of comparison across plans and reflect the most up-to-date industry standards, consistent with our past work and the most recent government accounting guidelines.

Figure 3 shows trends in aggregate assets and liabilities since 1997. Fiscal 2014 data reflect the new reporting standards, which use the market value of assets and a different method for calculating liabilities. Figure 4 shows total state and local pension debt as a share of GDP.

Figures 3 and 4 (click on images)

New data provide for better measures of plan health

The new disclosure requirements under GASB allow for improved analysis of plan contribution policies compared with previously available data. Before the change, most researchers, including Pew, had to rely on the ARC as a means of comparison. But meeting contribution targets based on this reporting standard never ensured that states and cities were actually paying down their pension debts.

The new data included in public pension financial statements allow for measurement of whether an employer’s contribution policy achieves net amortization. That is the level at which employers’ annual contributions to a plan are sufficient to pay for the cost of new benefits in that year as well as offset any projected growth in pension debt after netting out employee contributions.

The National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA) accurately notes that using net amortization may not always recognize funding policies that are sustainable and that could reduce pension debt over the long term. However, for states following policies expected to address unfunded liabilities, the net amortization benchmark can help pension plan sponsors measure progress. In addition, Moody’s Investors Service’s latest analysis of contribution policies follows a very similar approach in terms of measuring whether states reduced unfunded pension liabilities in the current budget year. The Society of Actuaries Blue Ribbon Panel also noted the importance of contribution polices that pay down pension debt over a fixed time period.

Plan administrators also point out that the numbers disclosed under GASB rules will often differ from those that drive contribution policies. Most notably, GASB requires plans to report assets on a market basis, but plans’ funding policies typically calculate contributions using asset smoothing to recognize gains and losses over time. Other differences can affect liabilities, but these are expected to be limited. For instance, the discount rate requirements under the new GASB rules affect only a select number of troubled plans. Additionally, most plans were already calculating their liabilities using an entry age actuarial method—which takes into account workers’ likely pay increases in calculating pension costs—as required for new GASB disclosures.

Any credible approach to achieving full funding of pension promises needs to pay down pension debt over a reasonable time frame. Prior to this year, GASB standards provided state pension plans with significant leeway in calculating the ARC, which allowed for contribution policies that fell short of this goal. For example, these standards allowed states to reset the maximum 30-year payoff schedule annually. This approach may provide near-term budget relief, but it allows pension debt to grow and costs more in the long run. Because of its limitations, the ARC proved to be a minimum reporting standard rather than a model approach for pension funding.

The net amortization measure assesses the results of contribution policies without taking into account unexpected gains and losses. If plan assumptions are correct, plans receiving contributions meeting the net amortization benchmark will have their unfunded liabilities shrink. Pew’s analysis shows that most state pension plans didn’t receive sufficient contributions to meet this benchmark in 2014.

It is important to note that the net amortization calculation does not use the same discount rate for all plans—it relies on plans’ own individually chosen assumptions. Plans with higher assumed rates of return will have lower estimated costs of benefits, and that will lower the benchmark for positive amortization.

There is still no single measure of plan fiscal health, but effective contribution policies eventually achieve positive amortization. Along with funded ratios and supplemental disclosures on funding policy—including ARC calculations—net amortization provides an important benchmark for states and cities to consider.

Figure 5 shows each state’s net amortization as a share of covered payroll, the total salaries paid to current employees.

Figure 5 (click on image)

Net amortization provides fuller picture of contribution policy

Net amortization provides policymakers a clear picture of the effectiveness of a state’s contribution policy in terms of paying down pension debt in the near term. The data show that many states are not contributing enough to their pension funds to reduce unfunded liabilities—including some states that have paid the full ARC. The new net amortization benchmark provides a better assessment of contribution policies than prior measures did.

Under the new metric, Kentucky, New Jersey, Illinois, and Pennsylvania experienced the largest negative amortization, when adjusted by covered payroll. Plans in these states face significant challenges and have low funded ratios. And without the strong overall investment returns in 2014, net amortization shows that these states would have lost further ground. All four also fell short of paying what would have been the full ARC in 2014. Pennsylvania, however, has committed to large and steady increases in contributions, and is projected to reach positive amortization by 2018.

Of the 10 states with the strongest results on positive amortization, seven have historically paid about 95 percent of ARC. But this group includes three states—Nebraska, Oklahoma and Louisiana—that reported paying less than full ARC payments in recent years. Still, the three continued making progress in reducing pension debt.

Oklahoma’s performance reflects a 2011 change to cost of living adjustments (COLAs). After that policy change, the state’s current contribution policy was adequate to pay down the remaining pension debt. Louisiana sets higher standards than typical state pension plans in calculating its actuarial contribution. As a result, even though the state fell short of full ARC funding in 2012 and 2013, its contributions were enough to make progress on paying for pension debt in 2014. Nebraska’s numbers were driven by contribution timing as well as changes to the state’s contribution policy in 2013. Pew’s research indicates that most states with contribution policies sufficient to pay down pension debt used more conservative approaches targeted at reducing unfunded liabilities compared with states that failed to meet net amortization.

In other cases, states and participating local governments made full ARC payments but still fell short of reducing their pension debt because they followed 30-year payment plans that were refinanced annually. Alabama and Arizona, for example, have historically set actuarial contribution rates based on approaches that would not make progress on paying down pension debt. As a result, while both states paid every dollar that plan actuaries asked for, their unfunded liabilities increased and their funding rank relative to other states declined. Both states’ pension plans have recently changed contribution policies, with a goal of hitting positive amortization over time.

Low funding levels make it harder for states to make progress. Those with larger unfunded pension liabilities require substantially higher contributions to pay down debt because they generate less in the way of investment earnings. Connecticut is only 50 percent funded, but the state’s current contribution policies, which include a fixed amortization period to pay off the unfunded liability, are anticipated to start reducing debt in fiscal 2017. The state has made progress by increasing payments every year; in 2014, it made the highest contributions relative to payroll of all but three states.

Connecticut’s pension funds assume relatively high 8 percent returns, which means that the current policy is sustainable only under risky assumptions. This example shows the difficulties that face a fiscally challenged state trying to pay down pension debt, as well as how a state can improve funding policies over time.

Elsewhere, Virginia shows how states that recently adopted more responsible funding policies might not pay down pension debt immediately, though they will close their funding gaps over time. In 2013, the Virginia Retirement System (VRS) board adopted a stronger funding policy to pay off the unfunded liabilities over a fixed time period, a method known as a closed amortization schedule. State policymakers also enacted legislation to make full actuarial contributions by 2018.

West Virginia stands apart as having made the most progress on pension funding, increasing its funded ratio from 40 percent to 78 percent from 2003 to 2014. West Virginia has averaged payments equal to 95 percent of the ARC or higher for a decade, as have 21 other states, but it has followed a more aggressive funding policy than many of its peers. Tracking net amortization highlights the importance of analyzing how actuarial contributions are set.

Looking at net amortization allows policymakers to better compare contribution policies by measuring outcomes rather than inputs, using a consistent formula for liabilities and using the market value of assets. However, plans still use a range of investment return assumptions under which higher assumed rates of return lead to the reporting of lower liabilities and costs.

Looking forward: Measuring and managing cost uncertainty

Net amortization assesses what happens under current policy if everything goes as expected. However,in providing a fixed benefit, public employers take on a variety of risks—in particular, investment risk. In calculating the fiscal sustainability of a pension plan, looking at different scenarios in what is called sensitivity analysis or stress testing gives a more complete picture of future pension costs and projected pension debt.

The new GASB rules include some sensitivity analysis: Plans are required to estimate liabilities based on projected returns 1 percentage point above or below their assumed rate of return. The Society of Actuaries commissioned a Blue Ribbon Panel to issue recommendations on pension funding and governance, which included a more detailed stress testing approach. Finally, states such as California and Washington have taken the lead by publishing sensitivity analyses on their public pension plans to assess their fiscal sustainability under multiple investment scenarios. Given the importance of risk in understanding pension plans’ fiscal condition, Pew will be working to incorporate stress testing and sensitivity analysis into future reports on state pension funding levels.

Conclusion

The gap between the pension benefits that state governments have promised workers and the funding to pay for them remains significant. Many states have enacted reforms in recent years to help shrink that divide, but they also have benefited from strong investment returns.

Over the long term, however, these returns are uncertain. In addition, many states have not made contributions that would reduce plan debt under expected returns. New tools, such as net amortization, stress testing, and sensitivity analysis, provide policymakers with additional information to better evaluate the effectiveness of their policies and ensure that plans can achieve full funding over time—and that pension promises can be kept.

You can read the full Pew report on state pension funding gaps as of 2014 by clicking here. The report contains end notes and appendices. You can also download an Excel spreadsheet with state by state data from the report here.

Also, as shown below, the funded ratios increased in most states in FY 2014 (click on image):

Of course, as mentioned in the report, returns have come down over the last fiscal year and more importantly, interest rates have also declined and that is the primary driver of pension deficits.

The report is very useful and basically offers hope to many states struggling to address the problem of chronically underfunded public pensions. In this report, states like Kentucky, Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania should look at the success of the Virginia Retirement System and try to adopt better funding policies (ie. no contribution holidays, keep topping up your state pensions!).

However, the Pew report leaves out a lot of information. For example, it singles out “West Virginia as standing apart, having made the most progress on pension funding, increasing its funded ratio from 40 percent to 78 percent from 2003 to 2014.”

All this is true but there is no mention of a recent report by the National Institute of Retirement Security (click here to read it) which shows that West Virginia and other states that switched from a DB to DC plan did not help their existing underfunding problem and in fact increased pension costs (again, click here for more information)

All this to say you have to be extremely careful reading these reports because there is a lot of stuff left out, important things like switching from a DB to DC plan which is an absolutely terrible decision from a public policy perspective.

Importantly, switching to a DC pension plan won’t stop the pension Titanic from sinking, it will only accelerate widespread pension poverty and increase social welfare costs (and the national debt).

None of these important policy questions are discussed in The Pew Charitable Trusts’s report. Sure, it’s a useful report that gives us a snapshot of state pension funding gaps using the net amortization measure (and even that is deficient because they use their own assumed discount rates), but if offers little in terms of insights and policies that will improve retirement security in the United States.

Also, the trillion dollar gap has been contested. In the $6 trillion pension cover-up, I discussed why some experts think the figures being reported on state pension funding gaps by the Society of Actuaries vastly understate the real extent of the US public pension gaps. I’m not suggesting they’re right but we need a more fruitful, honest and transparent debate on all these important public policy issues or else succumb to Chicago’s pitchforks and torches.

What else do US state pensions need to do? They desperately need to adopt the governance that has allowed Canada’s radical pensions to forge ahead and become global leaders in terms of managing pension assets and liabilities.

In other words, there is a gross misconception that if you improve the funding policy, you will magically fix state pension deficits. Sure, this will no doubt help a lot but unless you fix the governance at these state pensions, you won’t make real long-lasting change to secure their long-term sustainability.

Instead of fixing their governance so they can manage more assets internally, it’s business as usual for US public pensions which are shifting more assets into private equity, ignoring the risks and forking over huge fees for mediocre returns. That’s a subject for another day but it’s not a winning strategy.

Lastly, I want to share with you an email I received earlier today from someone who thinks I don’t know what I’m talking about when discussing why the pension Titanic is sinking:

You’re missing the boat. Returns, including returns on pension funds, are ALWAYS spreads, not absolute numbers.

It does not matter how much pension funds return as an absolute number. What matters is how much they return with respect to inflation or deflation (the spread). What matters is purchasing power, not the absolute return number!

In a world that is deflating at 3% a year, a 1% return will do just fine!

I replied back:

I think you are missing the point, pensions are all based on a promise that they will have enough money to cover future liabilities. In a deflationary world, rates will remain ultra low or negative for years, which means low returns and more importantly soaring liabilities. The only spread that counts is the one between assets and liabilities and since the duration of liabilities is much bigger than the duration of assets, deflation will kill pensions, especially poorly governed, chronically underfunded US pensions.

On that note, enjoy your weekend, and try not to worry too much about Janet Yellen and Stanley Fisher’s remarks. I still maintain that the Fed would be very foolish to raise rates in a world struggling with strong deflationary headwinds.

And while some like Morgan Stanley’s Jonathan Garner see emerging markets turning the corner, I would caution all of you to be very careful with emerging markets, energy and commodity shares going forward, regardless of what the Fed decides to do (read my market insights here and here).