Reporter Ed Mendel covered the California capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.

A paper issued by Stanford graduates seven years ago helped shift public focus to what critics call a “hidden” pension debt. Now a paper issued by UC Berkeley’s Haas Institute last month argues that full pension funding is not needed and may even be harmful.

The Stanford paper came after record losses in crucial investment funds expected to pay two-thirds of future pension costs. Whether investment earnings forecasts used to offset or “discount” future pension debt are too optimistic became a key part of pension debate.

It’s not clear at this point, needless to say, that the UC paper will mark another turning point in the debate. But pension funding has not recovered from the huge investment losses nearly a decade ago, despite a lengthy bull market that has nearly tripled the Dow index.

The California Public Employees Retirement System, only 63 percent funded last month, fears investment losses in another big market downturn could be crippling. Even a prolonged stagnant or slumping market could erode the management outlook.

It seems possible (who knows how likely) that in the years ahead there may be a growing movement, out of necessity, to accept or rationalize low pension funding as normal, reducing the pressure for employer rate increases that are already at an all-time high.

Seven years ago, the Stanford graduate student paper contending that California’s three big public pension funds had a shortfall of $500 billion, not the reported $55.4 billion, drew national media attention.

A New York Times story called it a “hidden shortfall.” A Washington Post editorial said it’s “more evidence that state governments are not leveling with their citizens about the costs of pensions for public employees.”

The Stanford study, using the principles of financial economics, discounted future pension obligations using risk-free bonds, not government accounting rules that allow pension funds to use earnings forecasts for stocks and other higher-yielding investments.

Responding to economic forecasts, not accounting theory, pension funds have lowered their forecasts. CalPERS and CalSTRS recently dropped their discount rates from 7.5 percent to 7 percent, increasing the need for more employer rate increases to fill the funding gap.

Far from signaling that low funding is becoming acceptable, Gov. Brown told Bloomberg news early this month he thinks CalPERS, which covers half of all state and local government employees, will “probably” lower its earnings forecast again.

“All that imposes greater costs on local and state government,” Brown told Bloomberg. “The pressure will mount.”

The UC paper issued last month, “Funding Public Pensions: Is full funding a misguided goal?” by Tom Sgouros, did not get major media attention. A quick internet search finds articles in The Week, The Fiscal Times, and the American Retirement Association news.

Sgouros argues that the Governmental Accounting Standards Board goal of full funding is needed for private-sector pensions but not for pensions offered by state and local governments, which are unlikely to go out of business.

The paper examines the problems created by the accounting rules in eight different categories, including actuarial and political. The conclusion is that the rules result in the “waste” of government funds that could be used for basic services.

A pension plan is “mutual insurance” for a group, not an attempt at “intergenerational equity” in which those who receive the services of government employees pay for their pensions, instead of pushing the cost to future generations.

Under the right conditions, the paper argues, a pension system with much less than full funding can pay benefits indefinitely: “Unless the combination of funding level and demographhics creates a liquidity crisis, there is always room to ‘kick the can’ further.”

A cautionary example of extreme full funding is a federal law in 2006 requiring the U.S. Postal Service to estimate pension and retiree health care liabilities 75 years in advance. By 2015 the USPS had put aside $335 billion and was 83 percent funded over 75 years.

But building a “breathtaking” retirement fund resulted in major operating losses, said the paper, that “shorted new capital investment and service expansions and left the service open to persistent charges that it is an an obsolete money-loser.”

The example in the paper of how pension funds that reach “full funding” tend to raise pensions and cut employer contributions is the California State Teachers Retirement System around 2000, as described in a Legislative Analyst’s Office report.

The UC paper said accounting rules “have been a convenient club to wield against public employee unions,” enabling claims that poor pension funding shows “the public has been duped into obligations it cannot afford.”

The author argues that many union leaders have weakened their own position by demanding full funding of pensions and viewing suggested cost-cutting reforms as an attack on benefits.

The paper quotes a source of support mentioned by other skeptics of the need for fully funding pensions, a report by the Congressional Government Accountability Office in 2008.

“Many experts and officials to whom we spoke consider a funded ratio of 80 percent to be sufficient for public plans for a couple of reasons,” said the GAO report.

“First, it is unlikely that public entities will go out of business or cease operations as can happen with private sector employers, and state and local governments can spread the costs of unfunded liabilities over a period of up to 30 years under current GASB standards.”

Girard Miller, debunking 12 pension myths, said in a 2012 Governing magazine column the view that 80 percent funding is healthy comes from anonymous GAO and Pew sources and a federal requirement that private pensions take action when funding falls below 80 percent.

Miller said pension funds should be 125 percent funded at the market peak. Based on equity losses in 14 recessions since 1926, a pension plan 100 percent funded at the end of a business expansion is likely to lose 20 percentof its value during an average recession.

“A plan funded at 80 percent going into a recession will likely find itself funded at 65 percent at the cyclical trough — and that’s a toxic recipe calling for huge increases in employer contributions to thereafter pay off the unfunded liabilities,” Miller said.

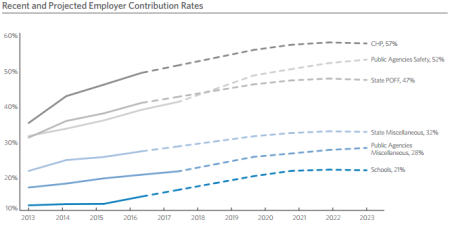

Now CalPERS is about 65 percent funded and phasing in the fourth in a decade-long series of rate increases ending in 2024. Getting back to 80 percent funding has been mentioned at the last two monthly CalPERS board meetings.

As a five-year strategic plan was adopted in February, board member Dana Hollinger suggested that a goal of 75 to 80 percent funding in five years would be more “attainable” and “realistic” than the goal that was aproved: 100 percent with acceptable risk, beyond five years.

Last week, Al Darby of the Retired Public Employees Association urged the board to reverse a short-term shift last September to lower-yielding investments expected to reduce the risk of funding dropping below 50 percent, another of the goals adopted in February.

“Restoring public equity allocation to pre-2016 levels would contribute a lot to reaching the 80 percent funding status that we are all hoping to restore,” Darby said.

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/mhuddelson/public_html/pension360.org/wp-includes/formatting.php on line 3712

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/mhuddelson/public_html/pension360.org/wp-includes/formatting.php on line 3712

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/mhuddelson/public_html/pension360.org/wp-includes/formatting.php on line 3712