Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Nick Thornton of Benefitpro reports, DC vs DB: 4 views on new EBRI data (h/t, Pension Tsunami):

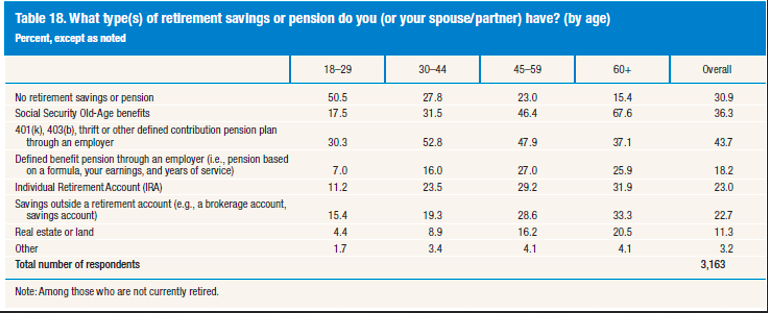

This week’s new data from the Employee Benefits Research Institute adds a new dimension to the vital question of the country’s retirement readiness.

In the report, researchers show that often, 401(k) plans can do a better job of replacing income in retirement than defined benefit plans can.

The report simulates savings outcomes for workers currently age 25 to 29, with at least 30 years of eligibility in a 401(k) plan.

It measures how often replacement rates of 60, 70, and 80 percent can be achieved by workers in four income quartiles if they participate in a 401(k) plan, compared to those levels of income replacement rates for participants in defined benefit plans.

When measured against a 60 percent income replacement rate, traditional pensions beat 401(k) for all workers, except those in the highest income quartile.

But as replacement rates are increased, 401(k) participants fare better, according EBRI.

Under the 70 percent replacement rate, workers in the top two income quartiles do resoundingly better than their counterparts in defined benefit pension plans.

Only 46 percent of workers in the second-highest income quartile can expect to replace 70 percent of income from a defined benefit plan, compared to 75 percent who contribute to a 401(k) plan.

When benchmarking against an 80 percent income replacement rate, workers in the top two income quartiles stand little chance of replacing as much income with traditional pension benefits, whereas 61 percent of workers in the second highest income quartile will be able to do so with distributions from a 401(k), and 59 percent of the best-paid workers will be able to do so through 401(k) savings, according to the modeling.

The take away: traditional defined benefit plans seem better for lowest income workers, especially the lower the income replacement rate.

Many 401(k) proponents will no doubt see the new data as supportive of their core argument: that participating in a defined contribution plan throughout the lion’s share of one’s working life will reap sufficient savings for a secure retirement.

Of course, others will disagree. Here is a look at four stakeholder views on the question of 401(k)’s efficacy, or inadequacy, in preparing the country for retirement.

Daniel Bennett, Managing Director, Advanced Pension Strategies

Bennett’s Southern California-based advisory provides specialized pension and tax-advantaged solutions for small employers.

He has real issues with EBRI’s new report. For starters, he says it’s based on generous return assumptions—the study uses an average annual return of 10.9 percent in 401(k) plans, which the institute tracked in plans between 2007 and 2013.

He also questions the validity of a 401(k) assessment that assumes 30 years of contributions, as EBRI’s report does.

Bennett tells BenefitsPro he is not partial to a defined benefit option to a 401(k), or vice versa, but he does admit to having a bias for small businesses.

“My field experience strongly indicates that 401(k)s are very deficient in providing positive retirement outcomes for anyone, owner and worker alike, in all but the largest firms and even then typically only for the higher wage earners,” said Bennett.

Selling 401(k) plans to the small business market is a “loss leader” for firms like Bennett’s.

He says providers are not incentivized to service the market, given the thin margins. He thinks the Department of Labor’s “draconian” fiduciary proposal will only make matters worse.

Defined contribution plans are part of the solution, he says, but don’t expect him to be in the camp that says 401(k)’s superiority is an open and shut case.

“Retirement Income outcomes are really the only thing that matters,” believes Bennett. “So when I read studies assuming 30 years of contributions and 10.9 percent growth rates, I can only sit there and scratch my head wondering what these guys are smoking.”

“They need to get out of the ivory tower and down in the trenches with me to see what is really happening,” he added.

Tony James, President and COO, Blackstone

A leader of one of world’s biggest private equity firms went on CNBC this week and said that the retirement crisis facing savers in their 20s and 30s will ultimately lead to a breakdown of the country’s financial structure.

“If we don’t do something, we’re going to have tens of millions of poor people and poverty rates not seen since the Great Depression,” James told CNBC.

He advocated a government-mandated Guaranteed Retirement Account system, of the kind famously recommended by labor economist Teresa Ghilarducci almost a decade ago.

Private equity firms like Blackstone have been trying to break into the 401(k) market for several years, with little documented success to date.

While James’ comments to CNBC were made outside the context of the EBRI report, he clearly would take issue with its assumptions.

He said 401(k)s typically earn 3 to 4 percent, while pension plans, which James said have an average allocation of 25 percent to alternative investments such as ones his firm manages, yield closer to 7 and 8 percent.

“The trick is to have these accounts invested like pension plans, so the money compounds over decades at 7 to 8 percent, not at 3 to 4,” said James.

Economic Policy Institute

The self-described non-partisan think tank advocates on economic issues affecting low- and moderate-income Americans (Teresa Ghilarducci sits on its board, as do several of the country’s largest labor leaders).

This week it published its own report, claiming in 2014, “distributions from 401(k)s and similar accounts (including Individual Retirement Accounts (IRA), which are mostly rolled over from 401(k)s) came to less than $1,000 per year per person aged 65 and older.”

“On the other hand, seniors received nearly $6,000 annually on average from traditional pensions,” according to EPI’s blog post.

Its post was also independent of EBRI’s new study.

“Though 401(k) and IRA distributions will grow in importance in coming years, the amounts saved to date are inadequate and unequally distributed, and it is unlikely that distributions from these accounts will be enough to replace bygone pensions for most retirees, who will continue to rely on Social Security for the bulk of their incomes,” according to the institute.

Peter Brady, Senior Economist, Investment Company Institute (ICI)

The ICI, a trade group representing the interests of the mutual fund industry (Blackstone is a member), also works with EBRI to coordinate data on 401(k) savings rates.

Brady published a post, also independent of EBRI, calling to question the Economic Policy Institute’s defense of defined benefit plans.

“EPI has it wrong,” writes Brady. Its analysis is “highly misleading” for the following reasons, he argues.

- It’s using unreliable data. Its source, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey (CPS), has consistently undercounted the income that retirees receive from employer-sponsored retirement plans and IRAs.

- It’s backward looking. The people whose income it’s measuring, today’s retirees, haven’t enjoyed the benefits of today’s well-developed 401(k) system.

- It’s gotten the math wrong. EPI’s analysts simply mishandled the data in ways that minimized the value of 401(k) plan and IRA distributions.

Unlike Peter Brady who represents the mutual fund industry, I don’t question the non-partisan Economic Policy Institute or its findings that 401(k)s are a negligible source of retirement income for seniors.

In fact, maybe Brady is right for the wrong reasons. I would reckon the EPI has gotten the math wrong by overestimating the retirement income from 401(k)s which have been a monumental failure contributing to the ongoing retirement woes of millions of Americans getting crushed by pension poverty.

That is where I agree with Blackstone’s Tony James. 401(k)s are not the solution to America’s retirement crisis but neither is his idea of a government-mandated Guaranteed Retirement Account system which invests like U.S. pension funds getting eaten alive by hedge fund, private equity fund and real estate fund fees. James’s solution is great for the Blackstones of this world and Wall Street, but it won’t bolster America’s retirement system, which is why I ripped into it in my last comment.

Moreover, Daniel Bennett, Managing Director of Advanced Pension Strategies is right to question the new data from the Employee Benefits Research Institute. It’s based on unrealistic return assumptions which are even worse than the ones U.S. public pension funds use as they chase their rate-of-return fantasy foolishly believing they will achieve a 7-8% bogey in a deflationary supercycle which won’t end any time soon.

Let me add a fifth and sobering view to this debate between DB vs DC plans, one which I’ve already covered in a previous comment of mine on the brutal truth on DC plans. In that comment, I noted the following:

Take the time to read the research report by the Canadian Public Pension Leadership Council. The research paper, Shifting Public Sector DB Plans to DC – The Experience so far and Implications for Canada, examines the claim that converting public sector DB plans to DC is in the best interests of taxpayers and other stakeholders by studying the experience of other jurisdictions, including Australia, Michigan, Nebraska, New York City, Saskatchewan and Texas and applying those lessons here in Canada. I thank Brad Underwood for bringing this paper to my attention.

I’m glad Canada’s large public pension funds got together to fund this new initiative to properly inform the public on why converting public sector defined-benefit plans to private sector defined-contribution plans is a more costly option.

Skeptics will claim that this new association is biased and the findings of this paper support the continuing activities of their organizations. But if you ask me, it’s high time we put a nail in the coffin of defined-contribution plans once and for all. The overwhelming evidence on the benefits of defined-benefit plans is irrefutable, which is why I keep harping on enhancing the CPP for all Canadians regardless of whether they work in the public or private sector.

And while shifting to defined-contribution plans might make perfect rational sense for a private company, the state ends up paying the higher social costs of such a shift. As I recently discussed, trouble is brewing at Canada’s private DB plans, and with the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield sinking to a 16-month low today, I expect public and private pension deficits to swell (if the market crashes, it will be a disaster for all pensions!).

Folks, the next ten years will be very rough. Historic low rates, record inflows into hedge funds, the real possibility of global deflation emanating from Europe, will all impact the returns of public and private assets. In this environment, I can’t underscore how important it will be to be properly diversified and to manage assets and liabilities much more closely.

And if you think defined-contribution plans are the solution, think again. Why? Apart from the fact that they’re more costly because they don’t pool resources and lower fees — or pool investment risk and longevity risk — they are also subject to the vagaries of public markets, which will be very volatile in the decade(s) ahead and won’t offer anything close to the returns of the last 30 years. That much I can guarantee you (just look at the starting point with 10-year U.S. treasury yield at 2.3%, pensions will be lucky to achieve 5 or 6% rate of return objective).

Public pension funds are far from perfect, especially in the United States where the governance is awful and constrains states from properly compensating their public pension fund managers. But if countries are going to get serious about tackling pension poverty once and for all, they will bolster public pensions for all their citizens and introduce proper reforms to ensure the long-term sustainability of these plans.

Finally, if you think shifting public sector DB plans into DC plans will help lower public debt, think again. The social welfare costs of such a shift will completely swamp the short-term reduction in public debt. Only economic imbeciles at right-wing “think tanks” will argue against this but they’re completely and utterly clueless on what we need to improve pension policy for all our citizens.

The brutal truth on defined-contribution plans is they’re more costly and not properly diversified across public and private assets. More importantly, they will exacerbate pension poverty which is why we have to enhance the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) for all Canadians allowing more people to retire in dignity and security. These people will have a guaranteed income during their golden years and thus contribute more to sales taxes, reducing public debt.

In short, I believe that now is the time to introduce real change to Canada’s retirement system and enhance the CPP for all Canadians.

I’m also a big believer that the same thing needs to happen in the United States by enhancing the Social Security for all Americans, provided they get the governance right, pay their public pension fund managers properly to manage the bulk of the assets internally and introduce a shared risk pension model in their public pensions.

It’s high time the United States of America goes Dutch on pensions and follows the Canadian model of pension governance. Now more than ever, the U.S. needs to enhance Social Security for all Americans and implement the governance model that has worked so well in Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden (and even improve on it).

And some final thoughts for all of you confused between defined-benefit and defined-contribution plans. Nothing, and I mean nothing, compares to a well-governed defined-benefit plan. The very essence of the pension promise is based on what DB, not DC, plans offer. Only a well-governed public DB plan can offer retirees a guaranteed income for the rest of their life.

What are the main advantages of well-governed DB plans? They pool investment risk, longevity risk, and they significantly lower costs by bringing public and private investments and absolute return strategies internally to be managed by properly compensated pension fund managers. DB plans also offer huge benefits to the overall economy, ones that will bolster the economy in tough times and reduce long-term debt.

In short, there shouldn’t be four, five or more views on DB vs DC plans. The sooner policymakers accept the brutal truth on DC plans, the better off hard working people and the entire country will be over the very long run.

Photo jjMustang_79 via Flickr CC License