The federal law ERISA – the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 – regulates many aspects of private pension plans.

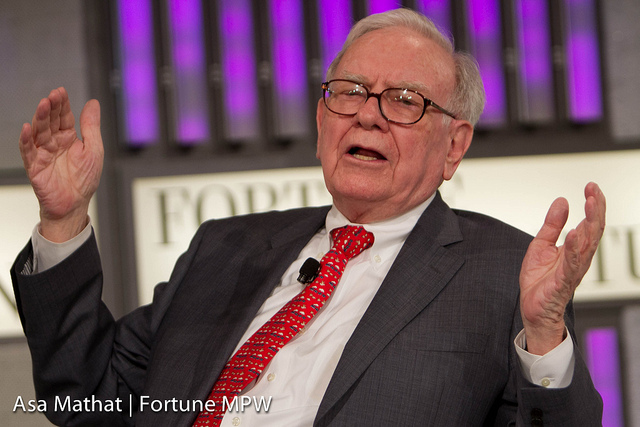

Should public pension funds be beholden to similar federal regulation? Alicia H. Munnell of the Center for Retirement Research explored this issue in a recent column published on MarketWatch.

Munnell writes:

In a recent meeting, an expert very supportive of public-sector employees raised the question of PERISA. These initials are shorthand for federal regulation of state and local pension plans—essentially extending some or all of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), which covers private-sector retirement plans, to the public sector.

I had not thought about such legislation since the early 1980s, and am not sure how I feel about it. On the one hand, proposals these days with regard to federal regulation tend to have a punitive tone—focusing mainly on getting public plans to stop using excessively high discount rates. On the other hand, serious underfunding in some plans is usually the result of delinquent behavior on the part of the sponsor.

So some regulation might be helpful, particularly now that the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) has clarified that its financial reporting standards do not constitute funding policy guidance, leaving a vacuum when it comes to public pension funding policies. But it is not clear that federal legislation could actually include funding requirements.

Munnell explores the origins of ERISA, and the reasons the federal law wound up covering private plans:

Here’s what I remember from the old days. Originally, governmental plans were included along with private plans in the legislative proposals leading up to the passage of ERISA. In the end, Congress exempted public plans from the Act and instead mandated a study of retirement plans at all levels of government to determine: 1) the adequacy of existing levels of participation, vesting, and financing; 2) the effectiveness of existing fiduciary standards; and 3) the necessity for federal legislation. The study concluded that serious problems existed and that federal regulation was necessary.

The experts believed that the federal government had the constitutional authority under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution to regulate reporting, disclosure, and fiduciary standards of state and local plans. On the other hand, the imposition of funding standards might affect the fiscal operations of state and local governments in a way that could threaten the sovereignty of the states. Hence, early legislative efforts omitted any funding regulation.

Some form of public plan legislation was introduced in each of the next four Congresses. While reporting, disclosure, and fiduciary standards may sound dull and routine, the proposed federal regulation met with passionate opposition during its long legislative history in the early 1980s. Opponents claimed that most public plans were under large systems that were generally well managed, and the public sector had not seen the flood of participant complaints witnessed in the private sector. Supporters contended that major reporting and disclosure deficiencies still existed and that the problems would persist since a major conflict of interest often exists between the goals of elected officials and sound financial management. In the absence of adequate reporting and disclosure, public officials could grant generous benefit increases and shift the costs to future taxpayers.

The two sides battled it out for several years but, in the end, no legislation was enacted for the federal regulation of state and local plans. My sense at this point, three decades later, is that federal regulation would be useful given the importance of state and local plans to the economy and the well-being of millions of workers. But the effort to pass such a bill would be worthwhile only if the legislation included funding requirements. And only the lawyers know whether funding requirements could pass constitutional muster.

Read Munnell’s entire piece here.