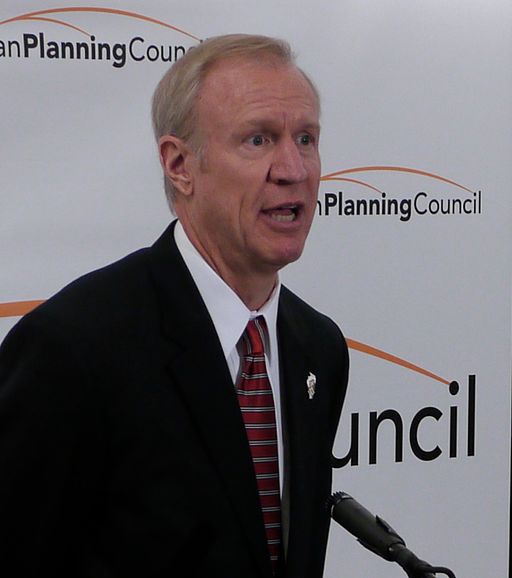

Illinois public schools that hand out late-career pay raises could be subject to heightened penalties under the Rauner administration.

Gov. Bruce Rauner this week laid out a series of pension-related measures as part of his budget proposal; among them was the idea of levying a penalty on schools that give late-career raises to teachers.

Illinois already penalizes schools for handing out such raises if they exceed 6 percent. Under Rauner’s proposal, schools would be penalized for any such raise that exceeds the cost of inflation, which is a much lower threshold.

More from the Daily Herald:

Tucked away in his plan to cut teachers’ pensions, though, is a detail school districts would have to be wary of should Rauner’s plans become law.

Here’s all it says on the list of details released publicly by the governor’s office: “Eliminates spiking.”

Rauner wants to change a state law that makes local school districts pay penalties if they give big end-of-career pay raises to teachers and administrators.

School districts can still give the pay raises, but the state says local officials have to pay for the pension consequences.

Now, school districts have to pay penalties if they give late-career pay raises of more than 6 percent. Rauner wants to enact penalties for those pay raises if they’re greater than the rate of inflation, which lately has been around 1 percent.

Suburban schools have already had to pay big bucks when they’ve been caught by the 6 percent law. For the 2012-2013 school year, for example, Elgin Area District U-46 had to pay $135,393.

The year before that, Schaumburg Township District 54 had to pay $489,841.

Most districts avoid big penalties, even writing in a 6 percent pay raise cap into their contracts with teachers. But 1 percent is a lot lower, of course.

“While a so-called reform was enacted in an effort to prevent pension spiking, teacher contracts in recent years have made the six percent cap a floor rather than a ceiling,” Rauner spokesman Lance Trover said.

A teacher’s salary during his/her final year of teaching plays a large role in determining pension benefits.

By Steven Vance [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons