Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

David Berman and Bertrand Marotte of the Globe and Mail report, CPPIB lands $12-billion deal for GE lending arm:

The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board has struck a $12-billion (U.S.) deal to acquire General Electric Co.’s private-equity lending arm, expanding its corporate lending capacity among smaller companies, where the fund had long sought a foothold.

The acquisition of Antares Capital is CPPIB’s largest deal to date. It is being backed by $3.85-billion of the pension fund’s own money, with the balance of the purchase price provided by debt from a consortium of international banks.

The deal is expected to close in the third quarter.

“It is extremely complementary to our existing business and that is why we are so interested in it,” said CPPIB chief executive officer Mark Wiseman.

Chicago-based Antares has a leading 20-per-cent share of the $96-billion business of providing loans for private-equity-backed transactions across industries. It specializes in the mid-market, focusing on companies with annual revenue as high as $1-billion.

The loans are generally rated below investment grade, and are therefore higher yielding than top-rated corporate debt.

CPPIB has an existing business lending larger amounts of money directly to companies, but the pension fund had been keen to expand its range.

“We had been undergoing a strategy review of the middle market for a number of years,” said Mark Jenkins, global head of private investments at CPPIB.

“So as soon as it became apparent that Antares was going to be one of the companies that was going to be sold, we knew that this was a good opportunity for us.”

CPPIB began discussions with GE in late April, soon after the U.S. conglomerate announced plans to sell off pieces of GE Capital, its finance arm.

The deal gives CPPIB about $11-billion in existing loans, mostly with durations under five years. The deal also comes with the Antares origination business, which will remain as a standalone unit under its existing management and brand name.

“Essentially, if we just bought the loan book, we’d be buying a melting ice cube. As the loans ran off, that portfolio would just wind down,” Mr. Wiseman said.

“What we’ve done is, we’ve bought the origination business that will continually refresh and replenish the portfolio. So essentially we’ve bought an ice cube that will never melt.”

He said other pension funds were likely rival bidders for Antares, but that CPPIB would consider bringing in partners as the deal progresses over the coming months.

“It’s our nature to partner,” Mr. Wiseman said. “If you look globally at what we do, we like working in concert with others.”

The Canadian fund manager is set apart from typical asset managers because of its long-term investment horizon and stable assets. It has been expanding into the United States to take advantage of the country’s relatively strong economic recovery but also as a diversification strategy.

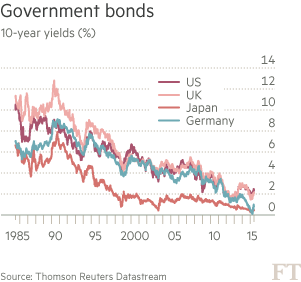

CPPIB has a mandate to generate average annual returns of 4 per cent, after accounting for inflation. This can be a struggle when government bonds, once the foundation of pension assets, are yielding well below that figure.

CPPIB is “really pushing the envelope here and being creative about what is going to work over the next 10, 20 years,” said Keith Ambachtsheer, director emeritus of the Rotman International Centre for Pension Management at the University of Toronto.

“There are risks in this business, especially if rates start surging higher, but I know they have qualified staff to handle the risks of each deal,” said Montreal-based pension and investment analyst Leo Kolivakis.

The $265-billion (Canadian) Canada Pension Plan fund has delivered an average annual return of 6.2 per cent, after inflation, over the past 10 years.

However, its foray into riskier assets appears to be paying off. The fund delivered a return of 18.3 per cent in its 2015 fiscal year ended March 31.

Barbara Shecter of the National Post also reports, CPPIB expands its debt business in $12B deal to buy Antares lending unit of GE Capital:

The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board has struck a $12-billion deal to acquire Antares Capital, the U.S. sponsor lending portfolio of GE Capital.

The Canadian pension investment giant will retain the management of Antares, and a staff of about 300, to continue generating loans.

CPPIB is better known for investments in real estate and infrastructure assets and sectors such as retail, but executives said Tuesday’s transaction is in the same category as CPPIB’s purchase last year of a reinsurance business, Wilton Re.

Both businesses were purchased with a portfolio of financial assets – reinsurance contracts in the case of Wilton Re, and loans in the case of the GE unit – and operational expertise to replenish those portfolios.

“This acquisition exemplifies our strategy to achieve scale in key sectors through platform investments,” said Mark Wiseman, the chief executive of CPPIB, adding that the acquisition will help diversify the fund’s investment portfolio.

Executives said the strategy makes sense for CPPIB, which invests the funds not needed by the Canada Pension Plan to pay current benefits and looks to generate returns over decades.

“The book of loans [in Antares] is like an ice cube in that the loans will run off over time because they will be repaid,” said Mark Jenkins, global head of private investments at CPPIB. “The platform that we’re acquiring alongside that asset allows us to continue to replenish that loan book such that we don’t have a shrinking ice cube in our hands.”

The Antares deal expands the Canadian pension organization’s presence in the private debt business by firmly establishing it in the mid-market. The acquisition will give CPPIB the expertise to make smaller loans in private equity transactions than it has traditionally done through its direct loan business, which targets positions between US$50 million and US$1 billion.

Jenkins said the Antares Capital and Wilton Re acquisitions aren’t as different from traditional CPPIB investments as they appear on the surface.

“This is no different (than) any other company we would buy… whether it be Neiman Marcus that’s a retailer or Informatica (Corp.), which we announced, which develops and sells software,” Jenkins said. “We’re effectively buying a business where the main widget that they make or, if you will, create is a loan that they have with a middle market private equity sponsor.”

Antares, which is based in Chicago, will continue to operate as a standalone business governed by its own board of directors.

The purchase gives the Canadian pension giant access to the management team including managing partners David Brackett and John Martin, as well as the employees responsible for generating loans across the United States through offices in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco.

Over the past five years, Antares has provided more than $120 billion in financing.

The acquisition is intended to complement and expand CPPIB’s principal credit investments portfolio. Formed in 2009, the principal credit investments group has invested more than $17 billion in global credit markets.

Jenkins said CPPIB has been looking to enter the mid-market for a couple of years. Customers tend to form strong relationships with their lenders, which leads to less turnover than in large-cap space, he said. Returns tend to better as well, due to better terms and stronger covenants for lenders than in the large-cap space.

CPPIB’s experience in the lending business and long-term investing horizon probably helped edge out competitors for the GE Capital business, Jenkins said, though the field of credible bidders would arguably have been small, given the specialized niche and ongoing funding requirements.

“I would say it was a very narrow group of institutions that could credibly put a bid in because of the scale of the transaction and also the certainty of funding,” he said.

“I think we had additional credibility because we know the business.”

Euan Rocha of Reuters also reports, Canada’s CPPIB to buy GE private equity lending arm for $12 billion:

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) said on Tuesday it has agreed to buy GE Capital’s private equity lending portfolio for $12 billion, in a deal that will greatly expand the largest Canadian pension fund’s lending business.

GE’s Antares unit is the leading lender to middle market private equity-backed transactions in the United States. In the past five years it has provided over $120 billion in financing.

“This provides us with a very unique opportunity to access the U.S. middle market space via a very attractive platform,” said Mark Jenkins, CPPIB’s global head of private investments.

GE’s retreat from lending and a broader move to reduce its exposure to its finance arm comes as U.S. regulators move to curb aggressive lending practices. GE announced plans in April to sell $200 billion worth of finance assets as it focuses on its industrial products business.

In a separate statement, GE said it plans to continue to run the Senior Secured Loan Program – a joint venture between affiliates of GE Capital and affiliates of Ares Capital; and its Middle Market Growth Program, a joint venture between affiliates of GE Capital and affiliates of Lone Star Funds; for a period of time to provide CPPIB the opportunity to work with both parties.

If CPPIB is unable to reach deals with both parties GE said it plans to wind down its investments in those two programs.

With this deal, GE said it has now finalized $55 billion worth of asset sales and it remains on track to complete roughly $100 billion worth of asset sales this year.

“This was the biggest thing we wanted to get done early and we did it in 60 days from a standing start,” said GE Capital’s head, Keith Sherin, adding he stood by GE’s rough target for agreements for $20 billion to $30 billion in finance asset sales by the end of the month.

GE and CPPIB expect the deal to close in the third quarter, pending regulatory approvals. JPMorgan Securities and Citigroup advised GE on this transaction, while Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley acted as CPPIB’s advisors.

CPPIB has invested over $16 billion in leveraged loans, high yield bonds, and mezzanine financings since 2009. This deal solidifies its foray into the lending sphere as it looks for investment opportunities for its roughly C$264 billion ($213.37 billion) in assets under management.

In his article, Scott Deveau of Bloomberg notes, Canada Pension Makes Biggest Bet Yet With $12 Billion GE Unit:

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board’s largest acquisition to date, the $12-billion purchase of a lending business from General Electric Co., is unusual for another reason: the Canadian firm did it alone.

The portfolio of loans in GE Capital’s U.S. Sponsor Finance business, and its management team, justified the risk of doing the deal without any partners, said Mark Jenkins, Canada Pension’s global head of private investments.

“When you put the two entities together, that’s the value for us,” Jenkins said in an interview.

The $12-billion price tag, of which Canada Pension paid $3.85 billion in equity, was a premium on the roughly $10 billion in loans on the books in the unit, called Antares Capital. The unit has a book value of about $3 billion, people familiar with the matter said last month.

Jenkins said it was justified. Already a lender for large companies globally, Canada Pension has had a harder time cracking the market for lending to smaller U.S. companies, Jenkins said. Canada Pension has C$265 billion ($215 billion) in assets.

“The comparative advantage Antares has is that you have long-term relationships with the middle-market sponsors, and that’s important,” Jenkins said. The management team, which will remain in place, was also an important component in generating future business, he said.

Another piece of GE’s business — an $8-billion Senior Secured Loan Program GE co-manages with Ares Management — was not included in the sale. Canada Pension remains open to talks with Ares about that business, Jenkins said.

Alternative Lenders

A U.S. regulatory clampdown on leveraged loans made by big banks has created a growth opportunity for alternative lenders, like the leveraged loan business. The U.S. Federal Reserve has discouraged debt levels from crossing certain thresholds and narrowed the window in which the loans must be paid down.

The measures have limited the lending power of big banks, Bobby LeBlanc, senior managing partner at Onex Corp., Canada’s largest private equity firm said last week.

“There is some constraint, but there is also alternative lenders that have popped up that are not regulated,” he said at an investor day. “Capital that’s not regulated always finds a way to our door.”

Major Divestiture

The deal marks the first major divestiture since GE announced a goal April 10 of unloading about $200 billion of GE Capital assets. Chief Executive Officer Jeffrey Immelt is speeding the exit of the banking division that imperiled the Fairfield, Connecticut-based parent company during the financial crisis.

GE Capital plans to continue to operate the joint venture with Ares for a period of time prior to closing to provide the parties an opportunity to work to together on a go-forward basis, the company said in Tuesday’s release.

If a mutual agreement can’t be reached, GE said it will retain the business so that it can execute the orderly wind down of the program.

You can also read an excellent article from the Canadian Press published in the CBC which points out the following:

CPPIB has been attracted to the U.S. middle market — which would be served by commercial banks in most countries, including Canada — by the structure of the loans, the lower loss rates and a stable customer base, Jenkins said.

Part of the reason the business has been very resilient through the ups and downs of the economic cycle is the relatively short duration of the loan agreements.

“These loans, on average, will mature after four years or be refinanced. So you’re constantly replenishing that loan book at different times through the cycle and you can adjust pricing.”

The Toronto-based fund manager will spend $3.85 billion to buy 100 per cent ownership of Antares Capital from GE Capital. The rest of the $12-billion transaction is in the form of new debt from a syndicate of global banks that will be used to run the business, Jenkins said.

Jenkins wouldn’t reveal what rate of return CPPIB expects from the Antares investment but said it’s in line with the overall investment portfolio on a risk-adjusted basis.

GE strategy to sell

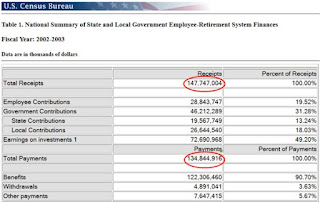

The CPP Investment Board oversees about $264.6 billion of assets on behalf of the Canada Pension Plan, which is funded by employee and employer contributions. The CPPIB invests surpluses that will eventually be used to supplement retirement payments for about 18 million contributors and beneficiaries.

General Electric said earlier this year it plans sell most of the assets of its GE Capital financial arm over the next 18 months, but planned to keep components that relate to its industrial businesses.

In its announcement from Fairfield, Conn., GE Capital said it will provide time for CPP Investment Board to work towards forging relationships with two partners of its U.S. Sponsor Finance business — which is primarily made up of Antares Capital.

Jenkins said CPPIB is willing to negotiate but the outcome won’t affect its purchase of Antares.

The deal is expected to close in the third quarter, subject to regulatory approvals.

Lastly, I highly recommend you take the time to read CPPIB’s press release on the deal:

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (“CPPIB”) announced today that an affiliate of its wholly owned subsidiary, CPPIB Credit Investments Inc. (“CPPIB Credit Investments”), has signed an agreement with GE Capital to acquire 100% of the Company’s U.S. sponsor lending portfolio, Antares Capital (“Antares” or “the Company”), alongside Antares management for a total consideration of US$12 billion. The transaction is subject to customary regulatory approvals and closing conditions and is expected to close during the third quarter of 2015.

Based in Chicago, Illinois, Antares is the leading lender to middle market private equity sponsors in the U.S., offering a “one-stop” source for lending and other services to middle market private equity sponsors within a US$96 billion a year market. Over the past five years, Antares has provided more than US$120 billion in financing.

“This acquisition exemplifies our strategy to achieve scale in key sectors through platform investments. It secures a market-leading business that is exceptionally well positioned to deliver value-building investment flows,” said Mark Wiseman, President & CEO, CPPIB. “In doing so, we are advancing the prudent diversification of our investment portfolio, strengthening the Fund even further.”

Upon closing, Antares will operate as a standalone, independent business governed by its own board of directors. The Company will retain the brand most associated with its long and impressive track record in the U.S. middle market, Antares Capital, and the team responsible for its long-term success led by its Managing Partners, David Brackett and John Martin. The acquisition will expand and complement CPPIB’s existing Principal Credit Investments portfolio.

“We have been studying the attractive economics of the U.S. middle market lending sector for several years. Antares represents a rare opportunity to invest in the leading lender in this segment of the market and involving companies owned by private equity sponsors,” said Mark Jenkins, Senior Managing Director & Global Head of Private Investments, CPPIB. “With this single transaction, we immediately acquire turn-key scale and a long-term partnership with the best, most experienced management team in the market. This business is extremely complementary to our existing business, which is not focused on the middle market.”

Antares’ core business is diversified across multiple industries and sponsors, and the mid-market segment provides attractive supply/demand dynamics due to the changing landscape of lenders in this space. Antares will be a highly strategic, long-term platform investment for CPPIB Credit Investments.

“The management team has done an excellent job in growing and managing the business, and we look forward to working together with the entire Antares team to further grow the business over the long term,” said Mr. Jenkins. “In acquiring these highly prized assets, we are able to leverage our comparative advantages of a long investment horizon and a stable capital base. We view Antares as a long-term addition to our portfolio and we are confident that it will provide CPPIB access to these attractive assets for the long term.”

CPPIB Credit Investments will be partnering with Antares’ entire seasoned management team and its approximately 300 employees. Antares has successfully built long-term relationships with more than 300 middle market private equity sponsors over many years.

“We are excited to partner with CPPIB. We couldn’t imagine a better outcome to the sale process for our team or our customers,” said David Brackett, Managing Partner, Antares Capital. “CPPIB brings deep understanding and knowledge of our market and permanent capital, which will allow us to serve our customers in both good and challenging times. We also look forward to continuing to offer our clients our existing best-in-class financing products and anticipate broadening our capabilities.”

CPPIB Credit Investments’ desire and intention to invest follow-on growth funding at scale into the Antares platform and significant access to capital, should position Antares to grow and prosper for decades to come. CPPIB Credit Investments will stand ready to immediately invest follow-on capital into Antares post closing to support origination of unitranche loans for its clients at scale, as we believe this is a differentiated product that will support Antares’ market leading position.

“In partnering with CPPIB, Antares is ideally positioned to continue, and expand upon, its market leading support for our private equity sponsor client base,” said John Martin, Managing Partner, Antares Capital. “In CPPIB we will have a strategic owner who is committed to our business model, with unparalleled capital resources. Additionally, this partnership will allow Antares to better address the realities of today’s leveraged lending environment. Our team will invest side by side with CPPIB Credit Investments and is thrilled about having the opportunity to build our franchise in the years ahead.”

With investments and 36 professionals in the Americas, Europe and Asia, CPPIB’s Principal Credit Investments (PCI) group focuses on providing financing solutions both globally and across the capital structure. The group makes direct primary and secondary investments in leveraged loans, high yield bonds, mezzanine, intellectual property and other solutions. PCI participates in unique event-driven opportunities, such as acquisitions, refinancing, restructurings and recapitalizations, and targets positions between US$50 million to US$1 billion in any single credit. The team underwrites on a standalone basis or with select partners depending on the investment opportunity. Since its first investment in 2009, the group has invested over US$17 billion in the global credit markets.

Now, let me briefly provide you with my thoughts on this mega deal:

- CPPIB is over-exposed to large private equity funds where it pays hefty fees to invest with top global funds and co-invest along with them on bigger deals (it pays no fees on co-investments but still needs to invest with big funds to gain access to the bigger deals).

- In order to diversify the private equity portfolio away from this large-cap space into mid-market space, it would have to find many mid-market funds, paying out even more fees, to properly diversify its private equity portfolio into the U.S. mid-market.

- When GE announced it was divesting from some of its financial business for regulatory reasons, a gift was presented to CPPIB and Mark Jenkins and his team pounced on the opportunity.

- By buying Antares Capital from GE Capital at a premium, it made GE very happy and CPPIB will gain exposure to the U.S. mid-market space on a massive scale, avoiding paying fees to mid-market private equity funds.

- More importantly, CPPIB is buying a well established lending business generating steady cash flows as the loans mature relatively quickly and will be able to leverage off the senior managers of Antares Capital to gain important insights on the U.S. economy, insights no other pension fund in the world will be privy to.

- Also, by buying the business directly, it will keep operations going and will benefit from the origination and underwriting activities of this business and be able to use the knowledge of these senior managers as a source for consulting them on other deals (it remains to be seen how they will compensate these senior managers but it’s fair to say they will be the highest paid employees at CPPIB).

- For its part, Antares gets a solid partner with a long investment horizon. No more worrying about quarterly earnings results or big downturns in the economy, this deal will allow them to focus on the long run and building up the capacity of their business to an unprecedented scale. There were big private equity funds bidding for this business too but they aren’t the right fit because their investment horizon is much shorter than that of CPPIB. Antares will also benefit from synergies with CPPIB and their huge network of expert partners and bankers.

- There was a premium paid but in my opinion, it was justified as the returns and knowledge transfer from this deal over the very long-run will more than offset this premium.

- With this deal, CPPIB will be placed in an enviable position, one that others can only dream of. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if other large Canadian pension funds are asked to join them on this deal. That all remains to be seen.

Having said this, I want to temper my enthusiasm a little because I’ve worked as a senior economist at the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), a Crown corporation that among its functions, primarily assists Canadian banks to provide loans to small and medium-sized businesses. The mid-market space is much riskier than the large-cap space because it’s more economically sensitive, which is why the returns are better (to compensate for the extra risk).

Go back to read my comment on hedge funds preparing for war where I wrote:

[…] hedge funds and private equity funds are now lending to small businesses starving for credit. Having worked as a senior economist at the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), a Crown corporation that finances and consults small and medium-sized enterprises, I can only wish these private debt funds a lot of luck making money in this area.

True, U.S. job growth rebounded last month and the unemployment rate dropped to a near seven-year low of 5.4 percent, which bodes well for lending to small and medium-sized enterprises, but there’s still plenty of slack in the economy with the number of Americans not in the labor force rising to a record 93.2 million (most of those unemployed are women). Moreover, America’s risky recovery poses serious challenges to the economy and can come back to haunt these private debt lenders.

This is particularly true if a liquidity time bomb is triggered by the Fed and global deflation comes back to haunt us, spreading to America. At a recent AIMA luncheon I attended many participants dismissed this possibility stating we should prepare for global reflation.

But I’m still very worried and agree with Michael Feroli of JPMorgan Economics, there is a new structural slowdown for the U.S. economy and America’s retirement nightmare will exacerbate this slowdown.

In a recent and excellent interview you should all read, David Brackett, CEO of Antares, stated that the interest rate environment is “favorable” adding this on how high interest rates would need to rise to impact mid-market lenders:

…because you are dealing with two components, leverage levels and interest rates, that are variable, it is tough to figure out where that would be. Leverage levels could likely expand from where they are today. If we look at our performance in the crisis, our losses were minimal and our private equity sponsors were really supportive. I think we’re in a very favorable interest rate environment. There would have to be a major movement in rates, which isn’t happening.

I hope he’s right and while some hedge fund gurus are warning of the bigger short, I’m far more worried about global deflation and a new structural slowdown in the U.S. and global economy.

One private equity expert shared this with me on this mega deal with GE:

Deal looks strategic, not something they will sell onwards to someone else in a few years, so that is probably why they have no partners. Seems like a good fit for CPPIB, and captures more economics around their broader belief in the private markets. That said, it does feel like a market/credit cycle top type of transaction.

He added this: “Most notable is CPPIB putting more profile to Mark Jenkins,” to which I replied: “Yup, they’re grooming him to be the next Mark Wiseman” (he has big shoes to fill there).

So take a good look at Mark Jenkins, CPPIB’s global head of private investments (a Goldman alumnus), because I guarantee you he’s next in line once Mark Wiseman decides to step down.

Finally, while this deal has risks and has a nice premium attached to it, I think the synergies between CPPIB and Antares will far outweigh all the risks and it was a great deal for all parties involved, including GE (a core holding of the Oracle of Omaha).

More importantly, from a policy perspective, this deal illustrates why the federal government should move quickly to make mandatory enhancement of the CPP our country’s new retirement policy. CPPIB delivered exceptional results in fiscal 2015 and will continue to do so over the very long run by investing in public and private markets through funds and direct investments which lower the costs to the fund.

Photo credit: “Canada blank map” by Lokal_Profil image cut to remove USA by Paul Robinson – Vector map BlankMap-USA-states-Canada-provinces.svg.Modified by Lokal_Profil. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons