Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Jonathan Rochford, portfolio manager at Narrow Road Capital, wrote a guest comment for ValueWalk, The Dallas Pension Fiasco Is Just the Beginning (h/t, Jim Leech):

The recent blow-up of the Dallas Police and Fire Pension System was entirely predictable. Whilst it is tempting to blame unusual circumstances for the recent lock-up of redemptions and likely substantial reductions to pensions for those still in the fund, many other American pension funds are heading down the same road. The combination of overpriced financial markets, inadequate contributions and overly generous pension promises mean dozens of US local and state government pension plans will end up in the same situation. The simple maths and political factors at play mean what happened at GM, Chrysler, Detroit and now Dallas will happen nationwide in the coming decade. So, what’s happened in Dallas and why will it happen elsewhere?

The Dallas pension scheme has been underfunded for many years with the situation accelerating recently. As the table below shows, as at 1 January 2016 the pension plan had $2.68 billion of assets (AVA) against $5.95 billion of liabilities (AAL), making the funding ratio (AVA/AAL) a mere 45.1%. Despite equity markets recovering strongly over the last seven years, the value of the assets has fallen at the same time as the value of the liabilities has grown rapidly. The story of how such a seemingly odd outcome could occur dates back to decisions made long before the financial crisis (click on image).

Source: Dallas Police and Fire Pension SystemIn the late 1990’s, returns in financial markets had been strong for years leading many to believe that exceptional returns would continue. In this environment, the board that ran the Dallas plan decided that more generous pension terms could be offered to employees and that these could be funded by the higher expected returns without needing greater contributions from the Dallas municipality and its taxpayers. Exceptionally generous terms were introduced including the now notorious DROP accounts and inflated assumptions for cost of living adjustments (COLA). These changes meant that pension liabilities were guaranteed to skyrocket in future years, whilst there was no guarantee that investment returns and inflation levels would also be high. Dallas police and fire personnel were being offered the equivalent of a free lunch and they took full advantage.

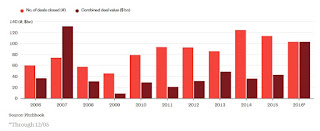

In the 2000’s the pension plan made some unusual investment decisions. A disproportionate amount of plan assets were invested in illiquid and exotic alternative investments. When the financial crisis struck these assets didn’t decline as much as the assets of other pension plans. However, this was merely a deferral of the inevitable write downs which came in the last two years after a change in management.

Dallas Pension – Recent Events

Throughout 2016 the pension board, the municipality and the State government bickered over who was responsible and who should pay to fix the mess. The State government blamed the municipality for the poor investment decisions. The municipality blamed the State government for creating a system that it could not control but was supposed to be responsible for. It also blamed the pension board for the overly generous changes they implemented. The pension board recognised the huge problem but offered only minor concessions arguing that plan participants were entitled to be paid in full in all circumstances. They asked the municipality for a one-off addition of $1.1 billion, equivalent to almost one year’s general fund revenue for the municipality.

As the funding ratio plummeted during 2016, plan participants became concerned that their generous pension entitlements might not be met. In other pension plans the employer might increase its contributions when these circumstances occurred, but in Dallas the municipality was already paying close to the legislative maximum. Police officers with high balances retired in record numbers, pulling out $500 million in four months in late 2016. Those who withdrew received 100% of what was owed, with those remaining seeing their position as measured by the funding ratio deteriorate further.

In November, when faced with $154 million of redemption requests and dwindling liquid assets, the pension board suspended redemptions. The funding ratio is now estimated to be around 36% with assets forecast to be exhausted in a decade. Litigation has begun with some plan participants suing to see their redemption requests honoured. The municipality has indicated it wants to claw back some of the generous benefits accrued since the changes in the 1990’s, though this is likely to only impact those who didn’t redeemed. The State has begun a criminal investigation. Everyone is looking to blame someone else, but not everyone has accepted that drastic pension cuts are inevitable.

Dallas Pension – The Interplay of Political Decisions and Financial Reality

The factors that led to Dallas pension fiasco are all too common. Politicians and their administrations often make decisions that are politically beneficial without taking into account financial reality. A generous pension scheme keeps workers and their unions onside, helping the politicians win re-election. However, the bill for the generosity is deferred beyond the current political generation, with unrealistic assumptions of future returns enabling the problem to be obscured. As financial markets tend to go up the escalator and down the elevator it is not until a market crash that the unrealistic return assumptions are exposed and the funding ratio collapses.

This is when a second political reality kicks in. In the case of Dallas, there are just under 10,000 participants in the pension plan compared to 1.258 million residents in the municipality. Plan participants therefore make up less than 1% of the population. If the Dallas municipality chose to fully fund the Dallas pension plan it would be require an enormous increase in taxes from the entire population in order to fund overly generous pensions for a very small minority of the population. For current politicians, it is far easier to blame the previous politicians and the pension board for the mess and see pensions for a select group cut by half or more than it is to sell a massive tax increase.

The legal position remains murky and it will take some time to clear up. The municipality is paying 37.5% of employee benefits into the pension plan, the maximum amount required by state law. Without a change in state legislation, it seems likely that the Dallas pension plan will have to bear almost all of the financial pain through pension reductions. If state legislation was changed to increase the burden on the municipality years of litigation could ensue with the potential for the municipality to declare bankruptcy as a strategic response. The appointment of an administrator during bankruptcy could see services reduced and/or taxes increased, but pension cuts would be all but a certainty.

Dallas Pension Isn’t the First and Won’t be the Last

It’s tempting to see the generous pension structure and bad investment decisions in Dallas as making it a special case. Detroit was seen by many as a special case when it went into bankruptcy in 2013 as it had seen its population fall by 25% in a decade. This depopulation left a smaller population base trying to fund the debt and pensions obligations incurred when the population was much larger. Growing debt and pension obligations are signs of what is to come for many local and state governments who have been living beyond their means for decades.

As well as building up pension obligations many US governments have been accruing explicit debt. The two are intertwined, with some governments issuing debt to make payments into their pension plans, often to close the underfunding gap. This is very much a short-term measure, as whether it is pension contributions or debt repayments both will either require high taxes and/or lower spending on government services in the future in order for these payments to be met.

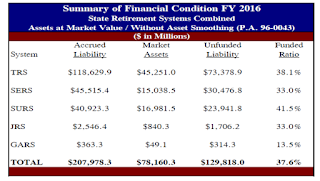

Pew Charitable Trusts research estimates a $1.5 trillion pension funding gap for the states alone, with Kentucky, New Jersey, Illinois, Pennsylvania and California going backwards at a rapid rate. Using a wider range of fiscal health measures the Mercatus Center has the five worst states as Kentucky, Illinois, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut. The table below shows the five state pension plans in Illinois, with an average funded ratio of just 37.6% (click on image).

Dallas Pension Source: Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and AccountabilityFor cities, Chicago is likely to be the next Detroit with the city and its school system both showing signs of financial distress. Chicago is trying to stem the bleeding with a grab bag of tax and other revenue increases but in the long term this makes the overall position worse.

Default is Almost Inevitable as the Weak get Weaker

The problem for Chicago and others trying to pay their debt and pension obligations by raising taxes is that this makes them unattractive destinations for businesses and workers. Growth covers many sins, as growth creates more jobs and drags more people into the area. This increases the tax base and lessens the burden from previous commitments on those already there. Well managed, low tax jurisdictions benefit from a positive feedback loop.

For states and municipalities in decline, their best taxpayers are the first to leave when the tax burden increases. Young college educated workers with professional jobs generate substantial income and sales tax revenue but require little in the way of education and healthcare expenditure. This cohort has many options for work elsewhere and can easily relocate. Chicago and Illinois are bleeding people, with the flight of millionaires particularly detrimental on revenues.

Those who own property are caught in a catch 22; property taxes and declining population have pushed property prices down, potentially creating negative equity. But staying means a bigger drain on the household budget as property taxes are the most efficient way to raise revenue and therefore become the tax increased the most. If too many people leave property prices plummet as they have in Detroit, making it even more difficult to collect property taxes as these are typically calculated as a percentage of the property valuation. Bankruptcy becomes inevitable as a poorer and older population base that remains simply cannot support the debt and pension obligations incurred when the population base was larger and wealthier.

Dallas Pension – Will be Reduced, but Bondholders Will Fare Worst

The playbook from the Detroit bankruptcy is likely to be used repeatedly in the coming decade. When a bankruptcy occurs and an administrator is appointed a very clear order of priority emerges. Firstly, services must be provided otherwise voters/taxpayers will leave or revolt. There may need to be cuts to balance the budget but if there is no police force, water or waste collection the city will cease to function.

Secondly, pensions will be reduced to match the available assets quarantined to meet pension obligations and the ability of the budget to provide some contribution. If the budget doesn’t have capacity or the legal obligation to contribute more to pension funding, pensioners should expect their payments to be cut to something like the funding percentage. For Dallas and the Dallas pension plans in Illinois this means payments cut by more than half.

Third in line are financial debtors. Bondholders and lenders don’t vote and they are seen as a bunch of faceless wealthy individuals and institutions who mostly reside out of state. They effectively rank behind pensioners, who are people who predominantly reside in the state and who vote, even though the two groups technically might rank equally. This makes state and local government debt a great candidate for a CDS short as the recovery rate for unsecured debt is usually awful in the event of default.

Dallas Pension Canary In Coal Mine? The Next Crisis Will Trigger an Avalanche

At the risk of being labelled a Meredith Whitney style boy who cried wolf I expect that the next financial crisis will trigger a wholesale revaluation of the creditworthiness of US state and local government debt. I have no crystal ball for when this will happen, but it is almost certain that the next decade will contain another substantial decline in asset prices. This will impact state and local governments and their pension obligations in two major ways.

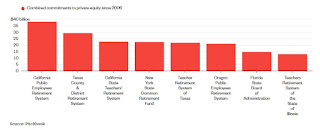

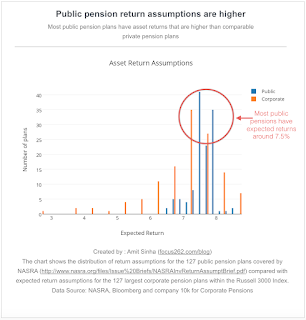

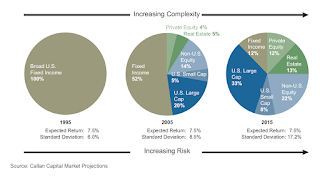

Firstly, asset prices will fall causing underfunded pensions to become even more obviously insolvent. Most US defined benefit pension funds are using 7.50% – 8.00% as their future return assumption. Using a 7.50% return assumption for a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, with ten year US treasuries at 2.50%, implies equities will return 10.8% every year going forward. In a low growth, low inflation environment this might be achievable for several years, but an eventual market crash will destroy any outperformance from the good years. The continued use of such high return assumptions is unrealistic and is being used to kick the can further down the road. The largest US public pension fund, Calpers, has recognised this and is reducing its return expectations from 7.50% to 7.00% over three years. This still implies a 10% return on equities for a 60/40 portfolio.

Secondly, downturns cause a reassessment of all types of debt with the highest risk and most unsustainable debt unable to be renewed. State and local governments with a history of increasing indebtedness and no realistic plan for reducing their debts may become unable to borrow at any price. This will force them to seek bankruptcy or an equivalent restructuring process. Once this happens for one mainland state (Illinois looks likely to be the first) lenders will dramatically reprice the possibility that it could happen elsewhere. Those who think states cannot file for bankruptcy should watch the process occurring in Puerto Rico, it will be repeated elsewhere. Barring a federal bailout, an overly indebted state or territory has no alternative other than to default on its debts. Raising taxes or cutting services will see the city or state depopulated. Politicians and voters are strongly incentivised to default.

Dallas Pension – Conclusion

Chronic budget deficits, growing indebtedness, excessive pension return assumptions and pension underfunding all set the stage for a wave of state and local government pension and debt defaults in the coming decade. As Detroit has shown this century, once an area loses its competitiveness its financial viability spirals downward. As taxes increase and services are cut the wealthiest and highest income earners leave slashing government revenues and increasing the burden on the older and poorer population that remains.

The next substantial fall in asset prices will sharpen the focus on budget deficits and pension underfunding, with the most indebted and underfunded states likely to find they are unable to rollover their debts at any price. Remaining residents will be negatively impacted, pensioners will see their payments slashed and bondholders will recover little, if any, of their debt. As there is virtually no political will to take action to avoid these problems investors should position their portfolios in expectation that these events will happen.

Written by Jonathan Rochford for Narrow Road Capital on January 17, 2017. Comments and criticisms are welcomed and can be sent to info@narrowroadcapital.com

Disclosure

This article has been prepared for educational purposes and is in no way meant to be a substitute for professional and tailored financial advice. It contains information derived and sourced from a broad list of third parties, and has been prepared on the basis that this third party information is accurate. This article expresses the views of the author at a point in time, and such views may change in the future with no obligation on Narrow Road Capital or the author to publicly update these views. Narrow Road Capital advises on and invests in a wide range of securities, including securities linked to the performance of various companies and financial institutions.

This is an excellent comment on why all roads lead to Dallas when it comes to chronically underfunded US public pensions with poor governance. I thank Jim leech for bringing it to my attention.

US state and local public pension plans need a miracle to get out of the hole they are in. Detroit was a basket case but Dallas and Chicago are not far behind. This particular case of the Dallas Police and Fire Pension once again demonstrates how public plans with little or no governance are a disaster waiting to happen.

The key passage from above is this one:

The combination of overpriced financial markets, inadequate contributions and overly generous pension promises mean dozens of US local and state government pension plans will end up in the same situation. The simple maths and political factors at play mean what happened at GM, Chrysler, Detroit and now Dallas will happen nationwide in the coming decade. So, what’s happened in Dallas and why will it happen elsewhere?

The simple math just doesn’t add up when you combine chronically underfunded public pensions with overly generous pension promises. You can promise pensioners the world but when the money runs out and you’re unable to raise property or sales taxes to fund gross incompetence and negligence, the only option left is to drastically reduce pension benefits.

If you don’t believe me, ask Greek pensioners. For years they were living under the delusion that their public pensions are well managed and that their pension payments are sacred, untouchable, good as gold. When the money ran out, they got a rude awakening as their pension benefits were slashed by 50, 60, 70% or more.

Pensions are all about managing assets and liabilities. If liabilities soar while assets plummet, there simply is no choice but to raise contributions and/or cut benefits. This is especially true if pensions are chronically underfunded. The math is simple and any rational person looking at the situation objectively would come to the same conclusion.

In response to dire pension calculus, state and local governments are trying to raise taxes and emit pension obligation bonds. These are feeble attempts to solve deep structural problems that can only be addressed properly through major reforms on pension governance and introducing some form of a shared risk model to make sure these pensions are sustainable over the long run.

Do all roads lead to Dallas? You bet, to Dallas, Chicago, Detroit and Greece, but so many people are living in Bubble Land that they simply can’t see the global pension storm is gathering steam and will soon threaten public finances everywhere, especially in areas where chronic pension deficits abound.