Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Randy Diamond of Pensions & Investments reports, CalPERS balancing risks in review of lower return target:

The stakes are high as the CalPERS board debates whether to significantly decrease the nation’s largest public pension fund’s assumed rate of return, a move that could hamstring the budgets of contributing municipalities as well as prompt other public funds across the country to follow suit.

But if the retirement system doesn’t act, pushing to achieve an unrealistically high return could threaten the viability of the $299.5 billion fund itself, its top investment officer and consultants say.

“Being aggressive, having a reasonable amount of volatility and (being) wrong could lead to an unrecoverable loss,” Andrew Junkin, president of Wilshire Consulting, the system’s general investment consultant, told the board at a November meeting. CalPERS’ current portfolio is pegged to a 7.5% return and a 13% volatility rate.

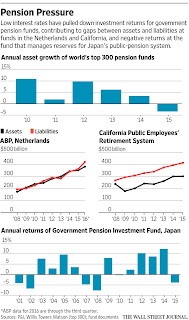

The chief investment officer of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and its investment consultants now say that assumed annualized rate of return is unlikely to be achieved over the next decade, given updated capital market assumptions that show a slow-growing economy and continued low interest rates.

Still, cities, towns and school districts that are part of the Sacramento-based system say they can’t afford increased contributions they would be forced to pay to provide pension benefits if the return rate is lowered.

A decision could come in February.

Unlike other public plans that have leaned toward modest rate of return reductions, a key CalPERS committee is expected to be presented with a plan in December that’s considerably more aggressive.

That was set in motion Nov. 15 at a committee meeting when Mr. Junkin and CalPERS CIO Theodore Eliopoulos said 6% is a more realistic return over the next decade.

At that meeting, it also was disclosed that CalPERS investment staff was reducing the fund’s allocation to equities in an effort to reduce risk.

Only a year earlier, CalPERS investment staff and consultants had agreed that CalPERS was on the right track with its 7.5% figure. So confident were they that they urged the board to approve a risk mitigation plan that did lower the rate of return, but over a 20-year period, and only when returns were in excess of the 7.5% assumption.

Two years of subpar results — a 0.6% return for the fiscal year ended June 30 and a 2.4% return in fiscal 2015 — reduced views of what CalPERS can earn over the next decade. Mr. Junkin said at the November meeting that Wilshire was predicting an annual return of 6.21% for the next decade, down from its estimates of 7.1% a year earlier.

Indeed, Mr. Junkin and Mr. Eliopoulos said the system’s very survival could be at stake if board members don’t lower the rate of return. “Being conservative leads to higher contributions, but you still have a sustainable benefit to CalPERS members,” Mr. Junkin said.

The opinions were seconded by the system’s other major consultant, Pension Consulting Alliance, which also lowered its return forecast.

Shifting the burden

But a CalPERS return reduction would just move the burden to other government units. Groups representing municipal governments in California warn that some cities could be forced to make layoffs and major cuts in city services as well as face the risk of bankruptcy if they have to absorb the decline through higher contributions to CalPERS.

“This is big for us,” Dane Hutchings, a lobbyist with the League of California Cities, said in an interview. “We’ve got cities out there with half their general fund obligated to pension liabilities. How do you run a city with half a budget?”

CalPERS documents show that some governmental units could see their contributions more than double if the rate of return was lowered to 6%. Mr. Hutchings said bankruptcies might occur if cities had a major hike without it being phased in over a period of years. CalPERS’ annual report in September on funding levels and risks also warned of potential bankruptcies by governmental units if the rate of return was decreased.

If the CalPERS board approves a rate of return decrease in February, school districts and the state would see rate increases for their employees in July 2017. Cities and other governmental units would see rate increases beginning in July 2018.

Any significant return reduction by CalPERS, which covers more than 1.5 million workers and retirees in 2,000 governmental units, would cause ripples both in and outside the state. That’s because making such a major rate cut in the assumed rate of return is rare.

Mr. Eliopoulos and the consultants are scheduled to make a specific recommendation on the return rate at a Dec. 20 meeting. But they were clear earlier this month that they feel the system won’t be able to earn much more than an annualized 6% over the next decade.

Gradual reductions

Thomas Aaron, a Chicago-based vice president and senior analyst at Moody’s Investors Services, said in an interview that many public plans have lowered their return assumption because of lower capital market assumptions and efforts to reduce risk. But Mr. Aaron said the reductions have happened “very gradually, it tends to be in increments of 25 or 50 basis points.”

Statistics from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators show that 43 of 137 public plans have lowered their return assumption since June 30, 2014. But NASRA statistics show only nine plans out of 127 are below 7% and none has gone below 6.5%.

“CalPERS is the largest pension system in the country; definitely if CalPERS were to make a significant reduction, other plans would take notice,” said Mr. Aaron.

Mr. Aaron said it would be hard to predict whether other public plans would follow. While there has been a general trend toward reduced return assumptions given capital market forecasts, some plans are sticking to higher assumptions because they believe in more optimistic longer-term investment return forecasts.

Compounding the problem is that CalPERS is 68% funded and cash-flow negative, meaning each year CalPERS is paying out more in benefits than it receives in contributions, Mr. Junkin said. CalPERS statistics show that the retirement system received $14 billion in contributions in the fiscal year ended June 30 but paid out $19 billion in benefits. To fill that $5 billion gap, the system was forced to sell investments.

CalPERS has an unfunded liability of $111 billion and critics have said unrealistic investment assumptions and inadequate contributions from employers and employees have led to the large gap.

Previously, CalPERS officials had said that any return assumption change would not occur until an asset allocation review was complete in February 2018. But Mr. Eliopoulos on Nov. 15 urged the board to act sooner, saying the U.S. could be in a recession by that date.

Richard Costigan, chairman of CalPERS finance and administration committee, said in an interview that he expects a recommendation and vote by the full board meeting in February, adding there is no requirement to wait until 2018 to consider the matter.

Some board members at the Nov. 15 meeting said CalPERS was moving too fast to implement a new assumption. “I’m a little confused at the panic and expediency that you guys are selling us right now,” said board member Theresa Taylor. “I think that we need to step back and breathe.”

But other board members suggested CalPERS needs to take immediate action even if it is uncomfortable.

Already adjusting

In a sense the system already has. Even without a formal return reduction, members of the investment staff have embarked on their own plan to reduce overall portfolio risk by reducing equity exposure, a policy supported by the board.

Mr. Eliopoulos said Nov. 15 that a pitfall of CalPERS’ current rate of return is the need to invest heavily in equities, taking more risk than might be prudent. He also said the system was reviewing its equity allocation.

The system’s latest investment report, issued Aug. 31, shows equity investments made up 51.1% or $155.4 billion of the system’s assets, down from 52.7% or $160 billion as of July 30 and down from 54.1% in July 2015.

CalPERS took $3.8 billion of the $4.6 billion in equity reduction and increased its cash position and other assets in its liquidity asset class. Liquidity assets grew to $9.6 billion as of Aug. 31 from $5.8 billion at the end of July.

But an even bigger cut in the equity portfolio occurred after the September investment committee meeting, when board members meeting in closed session reduced the allocation even more, sources said. It is unclear how big that cut was, but allocation guidelines allow equity to be cut to 44% of the total portfolio.

Board member J.J. Jelincic at the Nov. 15 meeting disclosed the new asset allocation was made at the September meeting closed session. But Mr. Jelincic said based on revisions the board approved in the system’s asset allocation, he felt the most CalPERS could earn was 6.25% a year because it was not taking enough risk.

Mr. Jelincic did not disclose the new asset allocation but said in an interview: “We are taking too little risk and walking away from the upside by not investing more in equities.”

So, CalPERS is getting real on future returns? It’s about time. I’ve long argued that US public pensions are delusional when it comes to their investment return assumptions and that if they used the discount rates most Canadian public pensions use, they’d be insolvent.

And J.J. Jelincic is right, taking too little risk in public equities is walking away from upside but he’s not being completely honest because when a mature pension plan with negative cash flows the size of CalPERS is underfunded, taking more risk in public equities can also spell doom because it introduces a lot more volatility in the asset mix (ie. downside risk).

When it comes to pensions, it’s not just about taking more risk, it’s about taking smarter risks, it’s about delivering high risk-adjusted returns over the long run to minimize the volatility in contribution risk.

Sure, CalPERS can allocate 60% of its portfolio to MSCI global stocks and hope for the best but can it then live through the volatility or worse still, a prolonged recession and bear market?

This too has huge implications because pension plans are path dependent which means the starting point matters and if the plan is underfunded or severely underfunded, taking more risk can put it in a deeper hole, one that it might never get out of.

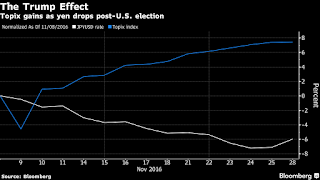

Yeah but Trump won the election, he’s going to spend on infrastructure, build a wall on the Mexican border and have Mexico pay for it, renegotiate NAFTA and all other trade agreements, cut corporate taxes, and “make America great again”. Bond yields and stocks have surged, lowering pension deficits, it’s all good news, so why lower return assumptions now?

Because my dear readers, Trump won’t trump the bond market, there are huge risks in the global economy, especially emerging markets, and that’s one reason why the US dollar keeps surging higher, which introduces other risks to US multinationals and corporate earnings.

I’ve been warning my readers to take Denmark’s dire pension warning seriously and that the global pension crisis is far from over. It’s actually gaining steam because the risks of deflation are not fading over the long run, they are still lurking in the background.

What else? Investment returns alone will not be enough to cover future liabilities. The best plans in the world, like Ontario Teachers and HOOPP, understood this years ago which is why they introduced a shared-risk model to partially or fully adjust inflation protection whenever their plans experience a deficit and will only restore it once fully funded status is achieved again.

In Canada, the governance is right, which means you don’t have anywhere near the government interference in public pensions as you do south of the border. Canadian pensions have been moving away from public markets increasingly investing directly in private markets like infrastructure, real estate and private equity. In order to do this, they got the governance right and compensate their pension fund managers properly.

Now, as the article above states, if CalPERS decides to lower its return assumptions, it’s a huge deal and it will have ripple effects in the US pension industry and California’s state and local governments.

The main reason why US public pensions don’t like lowering their return assumptions is because it effectively means public sector workers and state and local governments will need to contribute more to shore up these pensions. And this isn’t always feasible, which means property taxes might need to rise too to shore up these public pensions.

This is why I keep stating the pension crisis is deflationary. The shift from defined-benefit to defined-contribution plans shifts the retirement risk entirely onto employees which will eventually succumb to pension poverty once they outlive their meager savings (forcing higher social welfare costs for governments) and public sector pension deficits will only be met by lowering return assumptions, hiking the contributions, cutting benefits or raising property taxes, all of which take money out of the system and impact aggregate demand in a negative way.

This is why it’s a huge deal if CalPERS goes ahead and lowers its investment return assumptions. The ripple effects will be felt throughout the economy especially if other US public pensions follow suit.

Unfortunately, CalPERS doesn’t have much of choice because if it doesn’t lower its return target and its pension deficit grows, it will be forced to take more drastic actions down the road. And it’s not about being conservative, it’s about being realistic and getting real on future returns, especially now that California’s pensions are underfunded to the tune of one trillion dollars or $93K per household.