Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Lawrence Delevingne of Reuters reports, Struggling hedge funds still expense bonuses, bar tabs:

Investors are starting to sour on the idea of reimbursing hedge funds for multi-million dollar trader bonuses, lavish marketing dinners and trophy office space.

Powerful firms such as Citadel LLC and Millennium Management LLC charge clients for such costs through so-called “pass-through” fees, which can include everything from a new hire’s deferred compensation to travel to high-end technology.

It all adds up: investors often end up paying more than double the industry’s standard fees of 2 percent of assets and 20 percent of investment gains, which many already consider too high.

Investors have for years tolerated pass-through charges because of high net returns, but weak performance lately is testing their patience.

Clients of losing funds last year, including those managed by Blackstone Group LP’s (BX.N) Senfina Advisors LLC, Folger Hill Asset Management LP and Balyasny Asset Management LP, likely still paid fees far higher than 2 percent of assets.

Clients of shops that made money, including Paloma Partners and Hutchin Hill Capital LP, were left with returns of less than 5 percent partly because of a draining combination of pass-through and performance fees.

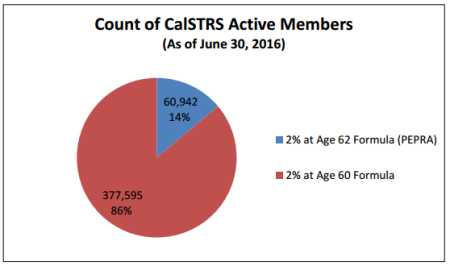

For a graphic on the hedge funds that passed through low returns, click on image below:

Millennium, the $34 billion New York firm led by billionaire Israel Englander, charged clients its usual fees of 5 or 6 percent of assets and 20 percent of gains in 2016, according to a person familiar with the situation. The charges left investors in Millennium’s flagship fund with a net return of just 3.3 percent.

Citadel, the $26 billion Chicago firm led by billionaire Kenneth Griffin, charged pass-through fees that added up to about 5.3 percent in 2015 and 6.3 percent in 2014, according to another person familiar with the situation. Charges for 2016 were not finalized, but the costs typically add up to between 5 and 10 percent of assets, separate from the 20 percent performance fee Citadel typically charges.

Citadel’s flagship fund returned 5 percent in 2016, far below its 19.5 percent annual average since 1990, according to the source who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity because the information is private.

All firms mentioned declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.

In 2014, consulting firm Cambridge Associates studied fees charged by multi-manager funds, which deploy various investment strategies using small teams and often include pass-throughs. Their clients lose 33 percent of profits to fees, on average, Cambridge found.

The report by research consultant Tomas Kmetko noted such funds would need to generate gross returns of roughly 19 percent to deliver a 10 percent net profit to clients.

‘STUNNING TO ME’

Defenders of pass-throughs said the fees were necessary to keep elite talent and provide traders with top technology. They said that firm executives were often among the largest investors in their funds and pay the same fees as clients.

But frustration is starting to show.

A 2016 survey by consulting firm EY found that 95 percent of investors prefer no pass-through expense. The report also said fewer investors support various types of pass-through fees than in the past.

“It’s stunning to me to think you would pay more than 2 percent,” said Marc Levine, chairman of the Illinois State Board of Investment, which has reduced its use of hedge funds. “That creates a huge hurdle to have the right alignment of interests.”

Investors pulled $11.5 billion from multi-strategy funds in 2016 after three consecutive years of net additions, according to data tracker eVestment. Redemptions for firms that use pass-through fees were not available.

Even with pass-through fees, firms like Citadel, Millennium and Paloma have produced double-digit net returns over the long-term. The Cambridge study also found that multi-manager funds generally performed better and with lower volatility than a global stock index.

“High fees and expenses are hard to stomach, particularly in a low-return environment, but it’s all about the net,” said Michael Hennessy, co-founder of hedge fund investment firm Morgan Creek Capital Management.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Citadel has used pass-through fees for an unusual purpose: developing intellectual property.

The firm relied partly on client fees to build an internal administration business starting in 2007. But only Citadel’s owners, including Griffin, benefited from the 2011 sale of the unit, Omnium LLC, to Northern Trust Corp for $100 million, plus $60 million or so in subsequent profit-sharing, two people familiar with the situation said.

Citadel noted in a 2016 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filing that some pass-through expenses are still used to develop intellectual property, the extent of which was unclear. Besides hedge funds, Citadel’s other business lines include Citadel Securities LLC, the powerful market-maker, and Citadel Technology LLC, a small portfolio management software provider.

Some Citadel hedge fund investors and advisers to them told Reuters they were unhappy about the firm charging clients to build technology whose profits Citadel alone will enjoy. “It’s really against the spirit of a partnership,” said one.

A spokesman for Citadel declined to comment.

A person familiar with the situation noted that Citadel put tens of millions of dollars into the businesses and disclosed to clients that only Citadel would benefit from related revenues. The person also noted Citadel’s high marks from an investor survey by industry publication Alpha for alignment of interests and independent oversight.

Gordon Barnes, global head of due diligence at Cambridge, said few hedge fund managers charge their investors for services provided by affiliates because of various problems it can cause.

“Even with the right legal disclosures, it rarely passes a basic fairness test,” Barnes said, declining to comment on any individual firm. “These arrangements tend to favor the manager’s interests.”

Interestingly, Zero Hedge recently reported that Citadel just paid a $22 million settlement for front-running its clients (great alignment of interests!). Chump change for Ken Griffin, one of the richest hedge fund managers alive and part of a handful of elite hedge fund managers in the world who are highly regarded among institutional investors.

But the good fat hedge fund years are coming to an abrupt end. Fed up with mediocre returns and outrageous fees, institutional investors are finally starting to drill down on performance and fees and asking themselves whether hedge funds — even “elite hedge funds” — are worth the trouble.

I know, everybody invests in a handful of hedge funds and Citadel, Millennium, Paloma and other ‘elite’ multi-strategy hedge funds figure prominently in the hedge fund portfolios of big pensions and sovereign wealth funds. All the more reason to cut this nonsense on fees and finally put and end to outrageous gouging, especially in a low return, low interest rate world.

“Yeah but Leo, it’s Ken Griffin and Izzy Englander, two of the best hedge fund managers alive!” So what? I don’t care if it’s Ken Griffin, Izzy Englander, Ray Dalio, Steve Cohen, Jim Simons, or even if George Soros started taking money from institutional investors, nonsense is nonsense and I will call it out each and every time!

Because trust me, smart pensions and sovereign wealth funds aren’t stupid. They see this nonsense and are hotly debating their allocations to hedge funds and whether they want to be part of the herd getting gouged on pass-through and other creative fees.

Listen to Michael Sabia’s interview in Davos at the end of my last comment. Notice how he deliberately avoided a discussion on hedge funds when asked about investing in them? All he said was “not hedge funds”. The Caisse has significantly curtailed its investments in external hedge funds. Why? Because, as Sabia states, they prefer focusing their attention on long-term illiquid alternatives, primarily infrastructure and real estate, which can provide them with stable yields over the long run without all the headline risk of hedge funds that quite frankly aren’t delivering what they are suppose to deliver — uncorrelated alpha under all market conditions!!

Now, is investing in infrastructure and real estate the solution for everyone? Of course not. Prices have been bid up, deals are very expensive and as Ron Mock stated in Davos, “you have to dig five times harder” to find good deals that really make sense in illiquid private alternatives.

And if my long-term forecast of global deflation materializes, all asset classes, including illiquid alternatives, are going to get roiled. Only good old US Treasuries are going to save your portfolio from getting clobbered, the one asset class that most institutional investors are avoiding as ‘Trumponomics’ arrives (dumb move, it’s not the beginning of the end for bonds!).

By the way, I know Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan still invests heavily in hedge funds but I would be surprised if their due diligence/ finance operations people would let any hedge fund pass through dubious fees on to their teachers. In fact, OTPP has set up a managed account platform at Inncocap to closely monitor all trading activity and operational risks of their external hedge funds.

Other large institutional investors in hedge funds, like Texas Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS), are tinkering with a new fee structure to get better alignment of interests with their external hedge funds. Imogen Rose-Smith of Institutional Investor reports, New Fee Structure Offers Hope to Besieged Hedge Funds (click on image):

You can read the rest of this article here. According to the article, TRS invests in 30 hedge funds and the plan has not disclosed how it will apply this new fee structure.

I think the new fee structure is a step in the right direction but if you ask me, I would get rid of the management fee for all hedge funds managing in excess of a billion dollars and leave the 20 percent performance fee (keep the management fee only for small emerging hedge fund managers that need it).

“But Leo, I’m an elite hedge fund manager and my portfolio managers are expensive, rent costs me a lot of money, not to mention my lifestyle and my wife who loves shopping at expensive boutiques in Paris, London, and New York and needs expensive cosmetic surgery to stay youthful and look good as we keep up with the billionaire socialites.”

Boo-Hoo! Cry me a river! Life is tough for all you struggling hedge fund managers charging pass-through fees to enjoy your billion dollar lifestyles? Let me take out the world’s smallest violin because if I had a dollar for all the lame, pathetic excuses hedge fund managers have thrown my way to justify their outrageous fees and mediocre returns, I’d be managing a multi-billion dollar global macro fund myself!

If you’re an elite hedge fund manager and are really as good as you claim, stop charging clients 2% to cover your fixed costs, focus on performance and delivering real alpha in all market environments, not on marketing and asset gathering (so you can collect more on that 2% management fee and become a big fat, lazy asset gatherer charging clients alpha fees for leveraged beta!).

I’m tired of hedge funds and private equity funds charging clients a bundle on fees, including management fees on billions, pass-through fees and a bunch of other hidden fees. And trust me, I’m not alone, a lot of smart institutional investors are finally putting the screws on hedge funds and private equity funds, telling them to shape up or ship out (it’s about time they smarten up).

Unfortunately, for every one large, smart institutional investor there are one hundred smaller, dumber public pension plans who literally have no clue what’s going on with their hedge funds and private equity funds. Case in point, the debacle at Dallas Police and Fire Pension System which I covered last week.

I’m convinced they still don’t know all the shenanigans that went on there and I bet you a lot of large and small US public pensions are in the same boat and petrified as to what will happen when fraud, corruption and outright gross incompetence are uncovered at their plans.

For all of you worried about your hedge funds and private equity funds, get in touch with my friends over at Phocion Investment Services in Montreal and let them drill down and do a comprehensive risk, investment, performance and operational due diligence on all your investments, not just in alternatives.

What’s that? You already use a “well-known consultant” providing you cookie cutter templates covering operational and investment risks at your hedge funds and private equity funds? Good luck with that approach, you deserve what’s coming to you.

On that note, I don’t get paid enough to provide you with my unadulterated, brutally honest, hard-hitting comments on pensions and investments. Unlike hedge funds and private equity funds charging you outrageous fees, I need to eat what I kill by trading and while I love writing these comments, it takes time away from what I truly love, analyzing markets and looking for great swing trading opportunities in bonds, biotech, tech and other sectors.

Please take the time to show your financial appreciation for all the work that goes into writing these comments by donating or subscribing to the PensionPulse blog on the top right-hand side under my beautiful mug shot. You simply won’t read better comments on pensions and investments anywhere else (you will read a bunch of washed down, ‘sanitized’ nonsense, however).