Here’s attorney Matthew Benson, offering a concise explanation of how Illinois’ pension system got to where it is today, the severity of its underfunding, and whether workers could be affected by reforms.

Tag: pension underfunding

Roadwork, Pensions and Congress’ Plan to Replenish the Highway Trust Fund

We could get a vote this week on the issue of replenishing the near-empty Highway Trust Fund, the federal fund used to finance transportation projects across the country. It’s funded by gas tax revenues, but due to run out of money within the month.

A solution has already been proposed and passed through the house, and now the Senate takes the reigns. If the fund runs out of money, many construction and infrastructure projects across the country would grind to a halt. But some critics say the the proposed solution could close the door on one problem and open the door for another.

What does any of this have to do with pensions? Josh Barro explains:

The Federal Highway Trust Fund is expected to run out of money in August. So, naturally, Congress is debating a temporary fix that involves letting corporations underfund their pension systems.

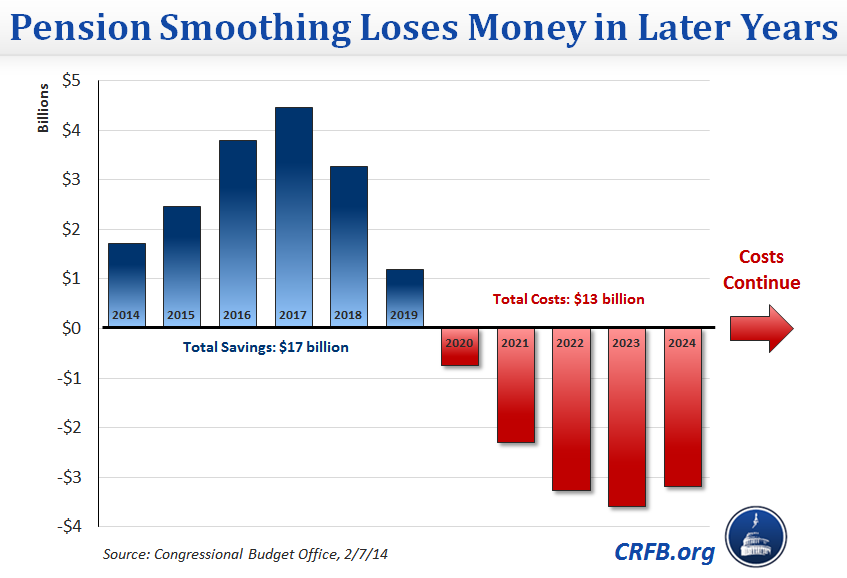

The latest proposal, which passed the Republican-controlled House Ways and Means Committee on Thursday, works like this: If you change corporate pension funding rules to let companies set aside less money today to pay for future benefits, they will report higher taxable profits. And if they have higher taxable profits, they will pay more in taxes over the 10-year budget window that Congress uses to write laws. Those added taxes can be diverted to the Federal Highway Trust Fund.

Unfortunately, this gimmick will also result in corporations paying less in taxes in later years, when they have to make up for the pension payments they’re missing now. But if it happens more than 10 years in the future, it doesn’t count in Congress’s method for calculating budget balance. “Fiscal responsibility,” as popularly defined in Washington, ignores anything that happens after 2024.

The official term for this method is called “smoothing.” Len Boselovic at the Pittsburg Post-Gazette gets into even more detail on the topic:

Smoothing affects the way pension funds value their liabilities, the benefits they are obligated to pay to retirees and their beneficiaries. The current value of those future obligations is based on a discount rate, which is determined by current interest rates. As Mr. Cole explains at www.taxfoundation.org/blog, if the future value of a pension benefit is $1, using a 4 percent discount rate puts the current value of the benefit at 96 cents. Using a 6 percent discount rate values it at 94 cents.

In other words, the higher the discount rate, the lower the current value of a pension fund’s obligations. The lower those obligations are, the less money a company has to contribute to its pension fund to comply with federal pension funding rules.

Interest rates have remained stubbornly low — forcing companies to contribute more to their pension funds. While that should make the funds better funded and put current and future retirees at ease, it crimps federal tax revenue. That’s because pension fund contributions are tax deductible. The more a company contributes to its pension fund, the less it contributes to the IRS.

Lawmakers who grasp that concept figure they can kill two birds with one stone: give pension funds relief from low interest rates and boost federal highway funding. They want to “smooth” the impact of lower interest rates by allowing companies to use a higher discount rate. That would lower companies’s pension funding requirements but raise their tax bills. The extra tax revenue would pay for transportation projects.

It’s an interesting way for Congress to approach this problem. But, as Pension360 has covered in the past, it’s a solution that causes its own problems, as Public Sector Inc. explains:

None of this is free, of course. Aside from the dangerous trend of allowing private firms to purposely underfund their pensions, the plan boosts federal revenues today at the cost of increasing the deficit over the long term.

Given this proposal, you would think that everything is just peachy with funding of private sector pensions in America. But The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, which is responsible for insuring private pensions, just put out a report estimating it’s on an eight-year path to insolvency itself.

The nation’s laws dictating private sector pension standards were enacted to protect retirement plans. But Congress, in its endless quest for more revenues, can’t even live by the standards that it imposed on companies.

Pension360 will keep you updated on subsequent developments in this story.

Pension Obligation Bonds Help Some Governments But Hurt Many More, Says New Report

New Jersey, Illinois, and California.

Those are the states that, more than any others, have frequently scrambled to pay down their pension obligations by issuing a financial tool called Pension Obligation Bonds (POBs). Over the last three decades, those three states have issued a total of $25 billion worth of POBs in an attempt to ease the heavy burden of their pension systems’ on state finances.

But what are POBs, and do they work as advertised? A new report from the Center for Retirement Research sheds light on that question and suggests that POBs may not be beneficial, after all. But first, what exactly is a POB? From Governing:

The tool, called Pension Obligation Bonds (commonly referred to as POBs), allows governments to issue taxable bonds for the purposes of putting money toward or fully paying off the unfunded portion of a pension liability. The proceeds from the bond issue go in the pension fund. The theory is that the rate of return on the investment will be greater than the interest rate the government pays to bond investors so that the transaction is favorable to the government; it makes money off the deal.

The concept is simple enough. And, in theory, it’s pretty clever. But in practice? Well, let’s just say timing is key. And many state and local governments have failed to get the timing right. It has cost them dearly, as Liz Farmer summarizes:

The report noted that the governments more likely to issue POBs are ones that have pension plans that represent “substantial obligations.” The governments have large outstanding debt and are short of cash. However, rather than necessarily relieving such governments of financial pressures, the bonds actually create a more rigid financial environment. Issuing bond debt to pay off a long-term obligation like a pension liability turns a somewhat flexible pension obligation into a hard and fast annual debt payment. Thus, “governments that have issued a POB have reduced their financial flexibility,” the study says.

POBs’ net returns (what the investment has earns after making bond payments) has varied, depending on when the bonds were issued. According to the center’s research, the net rate of return has averaged in the low, single digits for most years (the 30-year average is 1.5 percent). Governments that issued Pension Obligation Bonds in 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2007 actually lost money on their investment. Detroit, for example, issued debt at the peak of the market in the mid-2000s to fund its pension plan and did so using a complicated interest rate swap deal. The result was that the deal went the wrong way for the city. Detroit was still on the hook to pay bondholders and though its pension was well funded, it had even less day-to-day cash to meet its financial obligations. That debt played a key role in Detroit’s decision to file for bankruptcy last July.

Illinois, New Jersey, Detroit—that’s not the kind of company you want to keep if you are a local government trying to curb the burden of pension obligations. Though, the reputation of POBs may not be completely deserved. After all, just because struggling governments use them unwisely doesn’t mean POBs aren’t an effective tool when used the right way.

Although examples are hard to come by, POBs can be used effectively. In 2002 and 2003, Winnebago County and Sheboygan County in Wisconsin issued POBs to the tune of $7 million. They paid a 3 percent interest on that debt, but earned 20 percent returns on investments made with the borrowed money. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way.

You can read the CRR’s full report on POBs here.

Photo by Miran Rijavec Stan Dalone via Flickr CC License

![Video: Understanding the Illinois Pension Problem [Part 1]](http://pension360.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/271px-Flag_map_of_Illinois.png)