Reporter Ed Mendel covered the California Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.

After reaching agreements with all major creditors, San Bernardino is moving toward an exit from a four-year bankruptcy this fall without cutting public pensions, its largest and rapidly growing debt.

Last week U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Meredith Jury, saying the end is “in view,” scheduled another hearing June 16, when she plans to set a date for a hearing to confirm the exit plan, probably about 90 days later.

San Bernardino follows the path of previous bankruptcies in Vallejo and Stockton by limiting the main cuts in long-term debt to bonds and retiree health care, while raising taxes, slowly rebuilding reduced services, and leaving pensions untouched.

Now the prospect of cities and other local governments using bankruptcy to cut pensions or to get leverage in bargaining, which alarmed unions after Vallejo filed in 2008, may be fading as a pattern seems to be emerging.

Of the three cities that filed recession-era bankruptcies, San Bernardino had by far the strongest case for cutting pensions. The poorly managed city somehow seemed surprised to find that it was running out of cash and in danger of not making payroll.

After an emergency bankruptcy filing in August 2012, San Bernardino took the unprecedented step of skipping its legally required pension payment to CalPERS for the rest of the fiscal year, running up a tab of $13.5 million.

The California Public Employees Retirement System had grounds to cancel its contract with San Bernardino, likely resulting in pension cuts. But in mediation San Bernardino agreed to repay CalPERS with interest, $16 million, plus a $2 million penalty, all but $500,000 of which pays down city pension debt.

Part of the agreement announced in June 2014 was that the San Bernardino exit plan would not attempt to cut pensions. Four months later, a federal judge in the Stockton bankruptcy issued an opinion that a CalPERS pension can be cut in bankruptcy.

But even if the opinion had been issued before the mediated agreement, a lengthy San Bernardino disclosure statement heard by Judge Jury last week suggests that the city would not have attempted to cut pensions.

The San Bernardino disclosure gave the same basic reason as Stockton for not attempting to cut pensions in bankruptcy: Pensions are needed to be competitive in the job market, particularly for police.

“The city concluded that rejection of the CalPERS contract would lead to an exodus of City employees and impair the City’s future recruitment of new employees due to the noncompetitive compensation package it would offer new hires,” said the San Bernardino disclosure.

“This would be a particularly acute problem in law enforcement where retention and recruitment of police officers is already a serious issue in California, and where a defined benefit pension program is virtually a universal benefit.”

Apparently for the same reason, a pension reform approved by San Diego voters four years ago switched all new hires to 401(k)-style retirement plans, except for new police who continue to receive pensions.

If San Bernardino ended its CalPERS contract, Gov. Brown’s pension reform could speedup the feared exodus. To avoid being classified as “new hires” getting lower pensions, police and others choosing to leave the city would have to find another employer in CalPERS or a county system within six months.

“The departure of City employees upon rejection of the CalPERS Contract could be massive and sudden,” said the San Bernardino disclosure, which would “seriously jeopardize” public safety and other essential services.

San Bernardino does not provide federal Social Security for its employees. To remain competitive in the job market with a pension plan, said the disclosure, the city has “no ready, feasible, and cost-effective alternative” to CalPERS.

If San Bernardino did leave CalPERS, the city would have to pay for some type of new retirement plan while paying for pensions already earned under the CalPERS plan. The disclosure said the city would face a “hypothetical termination liability” of almost $2.5 billion.

And there would be a major legal battle. During mediation, said the disclosure, CalPERS took the position that its contract with the city cannot be rejected in bankruptcy or modified to reduce pensions and give the city financial relief.

When U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein issued an opinion in the Stockton case that CalPERS pensions can be cut in bankruptcy, CalPERS shrugged: the opinion is not legally binding and not a precedent.

In the Vallejo bankruptcy, city officials said they considered an attempt to cut pensions in bankruptcy but were dissuaded by a CalPERS threat of a long and costly court fight, possibly all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Unions responded to the Vallejo bankruptcy by obtaining legislation, AB 506 in 2011, requiring cities, before filing for bankruptcy, to go through a 60 to 90-day process to try to reach an agreement with creditors or declare a fiscal emergency.

Stockton went through the “neutral evaluation” process before filing for bankruptcy on June 28, 2012. A little more than a month later San Bernardino filed an emergency bankruptcy on Aug. 1, 2012.

Under the San Bernardino exit plan, annexation of the city and its fire department by the county fire district is expected to yield a $143 parcel tax. City firefighters transfer to the county retirement system with no reduction in pensions. The city would continue to pay for previously earned CalPERS pensions.

In exchange for no cuts in pensions, San Bernardino got an agreement with a federally appointed retiree committee to eliminate a $112 per month retiree health care subsidy, saving the city $411,250 this fiscal year.

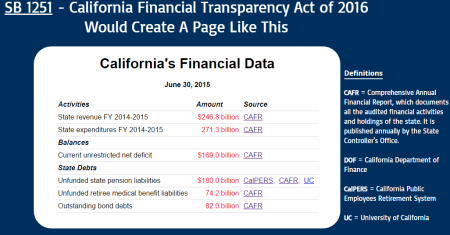

The disclosure shows the total annual San Bernardino payment to CalPERS is expected to increase from $14.2 million last fiscal year to $28.9 million by fiscal 2023-24.

In the latest CalPERS valuation, the safety plan for police was 76.2 percent funded with a debt or “unfunded liability” of $162.6 million. The annual employer rate of 44.8 percent of pay next fiscal year was expected to increase to 57.8 percent by fiscal 2021-22.

The CalPERS plan for miscellaneous employees was 78.1 percent funded with a $109.7 million unfunded liability. The annual employer rate, 26 percent of pay next fiscal year, was expected to increase to 34.4 percent by fiscal 2021-22.

Some pension costs are reduced, said the disclosure, through increased employee contributions, lower pensions for new hires under the governor’s reform, and contracting with private companies for solid waste removal and right-of-way cleanup.

A big step toward an exit plan was an agreement with Commerzbank to pay 40 percent of a $51 million pension obligation bond, up from the original proposal of 1 percent.

The judge was told last week that the city also has an agreement with 23 retired police officers who receive a supplemental pension through a private firm, the Public Agency Retirement System.

“We are not Detroit, we are not Stockton,” Judge Jury said in her concluding remarks last week. “We came into this case in a very different posture than the other cities. And therefore, the fact that it has taken us this long to get to confirmation was to be expected.”