Leo Kolivakis is a blogger, trader and independent senior pension and investment analyst. This post was originally published at Pension Pulse.

Devin Banerjee of Bloomberg reports, Blackstone’s Top Dealmaker Says Now Is The Most Difficult Period He’s Ever Experienced:

Joe Baratta, Blackstone Group LP’s top private equity dealmaker, can’t be too cautious right now.

“For any professional investor, this is the most difficult period we’ve ever experienced,” Baratta, Blackstone’s global head of private equity, said Tuesday, speaking at the WSJ Pro Private Equity Analyst Conference in New York. “You have historically high multiples of cash flows, low yields. I’ve never seen it in my career. It’s the most treacherous moment.”

Private equity managers have tussled with a difficult reality for several years. The same lofty valuations that created ideal conditions to sell holdings and pocket profits have made it exceedingly difficult to deploy money into new deals at attractive entry prices. Several executives, including Blackstone Chief Executive Officer Steve Schwarzman, have pinned those conditions squarely on the Federal Reserve’s near-zero interest rate policies.

Baratta, 45, said Blackstone isn’t finding value in large leveraged buyouts of publicly traded companies. Instead, the New York-based asset manager is targeting smaller companies with low leverage, he said.

‘Net Sellers’

The firm is still selling more assets than it’s buying, according to President Tony James.

“We’re net sellers on most things right now — prices are high,” James said in a Bloomberg Television interview Tuesday. “Interest rates are so low and there’s so much capital sloshing around the world.”

Blackstone finished gathering $18 billion for its latest private equity fund last year. The firm also has an energy private equity vehicle, which finished raising $4.5 billion last year.

Blackstone is close to striking its first deal by a new private equity fund, called Blackstone Core Equity Partners, Baratta said. The vehicle will have a 20-year life span, double the length of a traditional private equity fund.

The core equity fund, which has gotten $5 billion so far, will deploy $1 billion to $3 billion per deal, said Baratta. The transaction the firm is working on is valued at about $5 billion including debt, he said, without elaborating.

Blackstone, founded by Schwarzman and Peter G. Peterson in 1985, managed $356 billion in private equity holdings, real estate, credit assets and hedge funds as of June 30.

No doubt, these are treacherous times for private equity, hedge funds and especially active managers in public markets.

Facing dim prospects, Jon Marino of CNBC reports the barons of the buyout industry are now looking to buy each other out:

The barons of the buyout industry may need to buy one another out next.

KKR, the private equity firm co-founded by Henry Kravis, reportedly sought to tuck lender and investment firm HIG Capital under its growing corporate credit wing. That would mean adding about $20 billion in assets to Kravis’ company. Neither firm responded to a request for comment.

That’s not all; HarbourVest Partners, perhaps looking to take advantage of the discounted pound in the U.K., submitted a bid to buy SVG Capital, a British firm, but was rebuffed late last week. SVG Capital told HarbourVest, which is based in Boston, that it felt the bidder’s offer came up short — and revealed it has had talks with other “credible parties,” as well.

For some, it’s the right move, in order to beef up assets under management.

Public markets haven’t been too friendly to private equity firms’ initial public offerings, and as their senior leaders consider ways to exit long-held positions in their companies, options to net a return are dwindling. Tacking on other businesses could at least help juice management fees for buyers.

But for other private equity firms, it may be the only other option, beyond becoming zombie funds or winding down in the long run.

“The bloom has come off the rose for many big private equity firms,” said Richard Farley, chair of the leveraged finance group at law firm Kramer Levin.

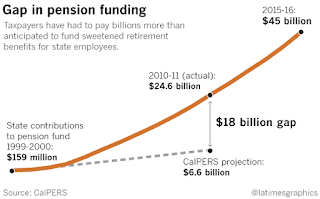

The urge to merge in the private equity industry should be growing, and it comes at a tough time for the private equity industry. Funding could become scarcer, as general partners leading top leveraged buyout firms are weighing whether to do deals. Some of their primary sources of cash — public pensions — are withdrawing from the business, in part because of abusive fee practices at certain firms.

Beyond the secular industry pressures faced by private equity firms, their returns have been compressed by a number of legislative and regulatory measures in the U.S.

In the wake of the global financial crisis, Washington regulators forced banks that fall under the purview of the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve to scale back how much they lent to private equity buyers’ deals, relative to the earnings before taxes, depreciation and amortization of those companies. Broadly speaking, banks are not permitted to lend more than six times a company’s Ebitda to get a deal done.

Further, leading up to this election there has been a great deal of hand-wringing by private equity executives that carried interest taxation, which allows them to be taxed at around half the going rate ordinary Americans face, may rise in coming years, further crimping profits. One legislative expert, asking to not be quoted, suggested it will remain difficult to pass legislation targeting carried interest, in part because other financial services sector businesses beyond private equity count on the tax break.

“Washington probably isn’t private equity’s biggest enemy,” the source said. “The real pressures are that the industry can’t generate the same kinds of returns their investors got used to.”

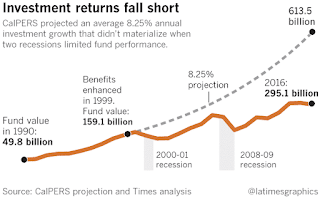

Indeed, the (not so) golden age of private equity is long gone and investors better get used to the industry’s diminishing returns. Just look at the private equity returns at CalPERS and other large pensions I cover in this blog, they have been declining quite significantly.

Moreover, the industry faces increased regulatory scrutiny and increased calls to be a lot more transparent on all the fees levied on investors, not that these initiatives are going anywhere.

In April of last year, I warned my readers to stick a fork in private equity. The point I made in that comment was the industry is far from dead but it’s undergoing a major transformation and facing important secular headwinds in a low yield/ high regulatory environment.

Even the best of the best private equity firms, like Blackstone, realize they need to adapt to the changing landscape or risk major withdrawals from clients.

In response, private equity’s top funds are looking to merge and they’re discovering Warren Buffett’s approach may indeed save them from extinction or at least help them navigate what is increasingly looking like a prolonged debt deflation cycle.

There’s a reason why Blackstone’s new fund, called Blackstone Core Equity Partners, will have a 20-year life span, double the length of a traditional private equity fund. Blackstone is implicitly telling investors to prepare for lower returns ahead and it will need to adopt a much longer investment horizon in order to produce better returns over public markets.

This isn’t a bad thing. In fact, by introducing new funds with longer life spans, private equity funds are better aligning their interests with those of their investors. They are also able to garner ever more assets (at reduced fees) which will help them grow their profits. And the name of the game is always asset gathering but it helps when these funds outperform too.

Let me end by informing my readers that Canada’s West Face Capital is aiming to raise $1.5 billion for a new private equity fund to make larger investments:

“We believe attractive market dislocations could occur over the next few years and we are making preparations with our investing partners,” Greg Boland, the head of Toronto-based West Face, said in an e-mail, declining to comment on the details of the fundraising. “The new committed draw fund will augment our ability to respond to large opportunities.”

West Face has reached out to potential investors about the new fund, which will invest in private and public securities and seek control through distressed transactions, said the person, who asked not to be identified because the matter is private.

The hedge fund is touting a 14 percent year-to-date return on its open-ended core fund in the fundraising efforts, the person said.

West Face focuses on event-oriented investing, specializing in distressed situations, private equity, public market investments and other transactions. The fund has been involved in several high-profile investments in recent years, including leading a group who acquired wireless carrier Wind Mobile in September 2014. That business was sold about 15 months later for C$1.6 billion ($1.2 billion) to Shaw Communications Inc., netting a sixfold return for the acquirers.

Not bad at all, while most hedge funds are struggling, some are still delivering exceptional returns and I like reading about Canadian hedge funds that are doing well.

By the way, a friendly reminder that the first ever cap intro conference for Quebec and Ontario emerging managers is taking place next Wednesday, October 5th, in Montreal. Details can be found here.

Also, another conference taking place in Montreal next week (October 5 and 6) is the AIMA Canada Investor Forum 2016. You can find details on this conference here.

I have decided to do my part to cover the first conference as it’s important to help emerging managers get the decent exposure they deserve and I haven’t decided whether I will attend the AIMA conference but there are some very good panel discussions taking place there.