When a pension system gives employees and employers a 20-year contribution holiday, you can bet it’ll run into some funding troubles down the line. University of California’s retirement system has been knee-deep in that harsh reality for years now. That has led to the borrowing of billions of dollars to cover funding shortfalls. And the University system has now taken out another massive loan.

From Ed Mendel at CalPensions:

UC regents last week approved borrowing another $700 million internally to help close a pension funding gap, bringing the total borrowed to $2.7 billion in a pension bond-like strategy with risks or rewards, depending on investment earnings.

Five years ago University of California employers and employees were paying nothing into the pension system. In a remarkable contribution “holiday” that began in 1990, payments into the system dropped to zero and stayed there for two decades.

After restarting in 2010, the employer contribution to the UC Retirement Plan increased from 12 to 14 percent of pay this month and most employee contributions increased from 6.5 to 8 percent of pay, a total of nearly $2 billion a year.

But the steady increase of contributions that were once zero still falls short of closing the pension funding gap. Last year UC Retirement had only 76 percent of the actuarially projected assets needed to pay pension obligations over the next three decades.

To help close the funding gap, UC borrowed $1.1 billion from its own Short-Term Investment Pool in 2011 and $937 million from external sources. The $700 million loan approved last week is from the short-term pool.

The UC Retirement fund, with assets valued at about $50 billion, expects to earn an average of 7.5 percent a year, the same as the California Public Employees Retirement System. Critics say the earnings forecast is too optimistic and conceals massive debt.

In what some call arbitrage, money borrowed at a low interest rate from the UC short-term pool (which earned 1.7 percent last year) and invested in the pension fund earns a profit if the return is the expected 7.5 percent or even a little less.

“I do feel we are on a little bit of a slippery slope here,” said Regent Fred Ruiz. “I think we have to be very cautious … The market changes from year to year, and if we don’t get the returns we need to have, then we are in great trouble.”

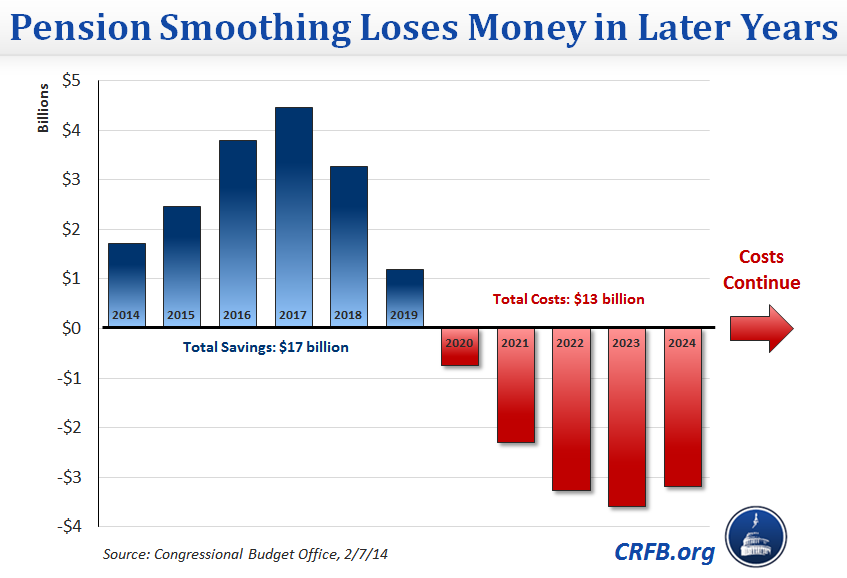

This is the same concept, essentially, as Pension Obligation Bonds. And, just like POBs, the outcome of this borrowing can either be of great benefit or great harm to the U of C pension system. Whether this turns out good or bad depends on future investment returns.

STUMP blogger Mary Pat Campbell gives her take on the dangers of U of C’s decision:

One should always match one’s borrowing to one’s accrual of expenses. It’s okay to finance the acquisition of an asset (such as a car or a house) with a loan that amortizes over the life of the asset. It’s not okay to take out a 30-year-loan to pay for a trip to Disney. The first is based on good financial principles, the second indicates you are living way beyond your means.

Short-term financing for operational expenses is fine if one has “lumpy” cash flows (which the UC system may have, depending on how they pay their staff. I get paid for my adjunct teaching only during the semester.) But even though they’re calling it a short-term pool, it sounds to me like what they’re doing is borrowing under short-term limits, but keeping rolling over the debt, as if it were a longer-term loan.

I really don’t like the sound of that.

That is something that could escalate rapidly should interest rates start to rise.

Bottom-line: borrowing money for a fake arbitrage is bad finance. The 7.5% return is just an assumption, not a sure thing. Real life returns vary a lot the way they invest it — and the loan interest is a sure thing, just as the pension benefits are a (supposed) sure thing.

We won’t know for years how this decision ultimately plays out for the University of California system. But you can bet the Regents have their fingers crossed.