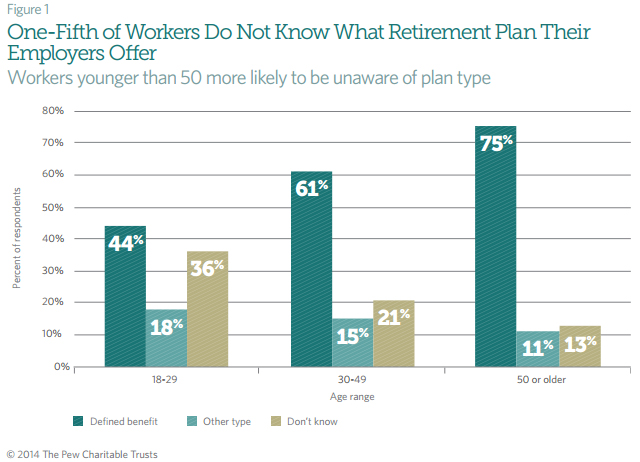

Robert Sarvis and the Competitive Enterprise Institute have released a new report on public pension debt in the United States. The report draws from several estimates of pension debt and produces a list of states with the highest (and lowest) burdens of pension debt on their shoulders.

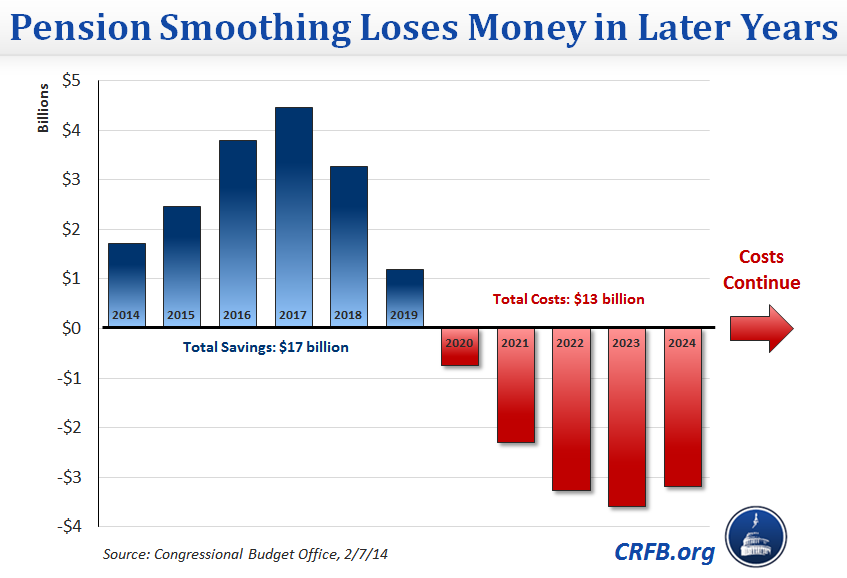

The report begins by laying out some of the reasons most states are shouldering massive pension debts:

One reason is legal. In many states, pension payments have stronger legal protections than other kinds of debt. This has made reform extremely difficult, as government employee unions can sue to block any scaling back of generous pension packages.

Then there is the politics. For years, government employee unions have effectively opposed efforts to control the costs of generous pension benefits. Meanwhile, politicians who rely on government unions for electoral support have been reluctant to pursue reform, as they find it much easier to pass the bill to future generations than to anger their union allies.

Another contributing factor has been math—or rather, bad math. For years, state governments have understated the underfunding of their pensions through the use of dubious accounting methods. This involves using a discount rate—the interest rate used to determine the present value of future cash flows—that is too high. This affects the valuation of liabilities and the level of governments’ contributions into their pension funds.

More on the ‘bad math’ portion of that argument:

In defined benefit plans, states are on the hook for payouts regardless of their pensions’ funding level. Therefore, the discount rate used in the valuation of pension liabilities should be a low-risk rate, because of the fixed nature of pension liabilities. Ideally, this should as low as the rate of return on 10- to 20-year Treasury bonds, which is in the 3 to 4 percent range.

However, in the U.S., most state and local governments use discount rates based on much higher investment return projections, usually of 7 to 8 percent a year. This usually leads to state and local governments making lower contributions, in the expectation of high investment returns making up for the gap. However, while such returns may be achievable at some times, they need to be achievable year-on-year in order for a pension fund to meet its payout obligations, which grow without interruption. Therefore, failing to achieve such high returns can result in pension underfunding that extends into the future. Discount rates based on high return projections also incentivize pension fund managers to seek higher returns. This encourages in-vesting in riskier assets, which incur large losses for investors when they go south.

For years, this practice was validated by the quasi-private Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB). To improve accounting, GASB recently introduced new standards that have pensions deemed underfunded—those with a funding level of under 80 percent—use a lower discount rate. However, pension plans deemed to be above 80 percent funded will still be able to use a high discount rate. Thus, the new GASB standards do not go nearly far enough to end the dubious accounting practices that have exacerbated state pension underfunding by hiding its extent.

Of course, these factors affect different states in different ways. Not all states use an 8 percent discount rate, although many do. That’s why the report breaks down which states are the worst off based. We won’t give away the results–but there are some surprises. Click the link below to check out the results of this interesting study.