Stephen Herzenberg, the executive director of the Keystone Research Center, took to the newspaper on Monday to counter Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett’s argument that the best bet for saving the state’s pensions would be to switch new hires into a 401(k)-type plan.

Herzenberg claims in an op-ed that such a plan would provide no savings for the state, reduce benefits for retirees and actually increase the state’s pension debt.

Herzenberg starts by talking about the fees and other costs associated with 401(k) plans. From the op-ed, published in the Patriot-News:

For two years, Governor Corbett has advocated a shift from pooled, professionally managed, defined-benefit pensions to a system where each employee manages an individual account, similar to a private sector 401(k) plan.

[…]

How does the efficiency of today’s defined benefit pensions system translate, in bottom-line terms, measured by the level of contributions required to fund retirement? According to the National Institute on Retirement Security, individual 401(k)-style accounts cost 45% to 85% more than traditional pooled pensions to achieve the same retirement benefit. That’s a big efficiency gap.

A lot of this efficiency gap results from the fees that financial firms charge holders of individual accounts – for administration, for financial management and trading stocks, and for converting savings at retirement into a monthly pension check guaranteed until the end of life – an “annuity.” In essence, these fees are transfer from Main Street retirees to Wall Street. In an economy with stagnant middle-class incomes and all the gains for recent growth already going to the top, such a transfer seems like the last thing we need.

Given the high fees and low returns of 401(k)-style accounts, it is hardly a surprise that actuaries who have studied the Governor’s proposal for an immediate switch to them – or a more gradual switch under a new “hybrid” proposal that the Governor now supports – don’t find any savings.

Far from providing savings, in fact, this switch could result in a large upfront transition costs – because the investment returns on the existing pension plans would fall as the plans wind down. The Governor’s plan was projected to have a $42 billion transition cost.

He goes on to write that Corbett’s plan would be “highly inefficient” and would actually reduce retirement benefits. From the op-ed:

The switch would also reduce retirement benefits. This is not only bad for teachers, nurses, public safety personnel, and other public servants. It could also require a future wage increase to enable the state and school districts to attract and retain high-quality staff – another cost to taxpayers.

In his recent book on inequality, economist Thomas Piketty worries that high returns and low financial management costs are only accessible to massive pools of wealth. This means that the assets of the wealthiest individuals and families grow faster than the wealth of the rest of us. It reinforces the drfit back towards Gilded Age levels of wealth inequality.

But in the context of public sector retirement plans, defined-benefit pensions give taxpayers and the middle class the ability to grow their pooled retirement savings in the same manner as Warren Buffet and Bill Gates.

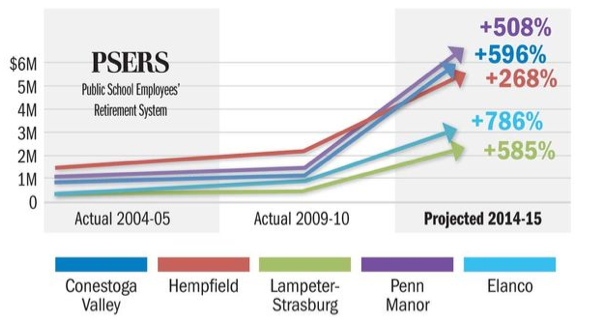

If define benefit pensions are poorly managed, as they have been in Pennsylvania, they do create some challenges. As with paying a credit card bill, if you don’t put in the required contributions you can run up a large expensive debt. But the way to fix that problem is to pay the required contributions, not to switch to a highly inefficient retirement savings vehicle.

Read the entire column here.